The leader of one of our main international financial institutions argues that we need to remember and learn from the cooperative spirit in which the Bretton Woods international financial system was born in 1944. Unfortunately the creation and later success of that system depended on the economic and financial dominance of a single self-interested nation, the United States. There is no such dominant player now, which makes the creation of a new international financial system very difficult.

A new multilateralism?

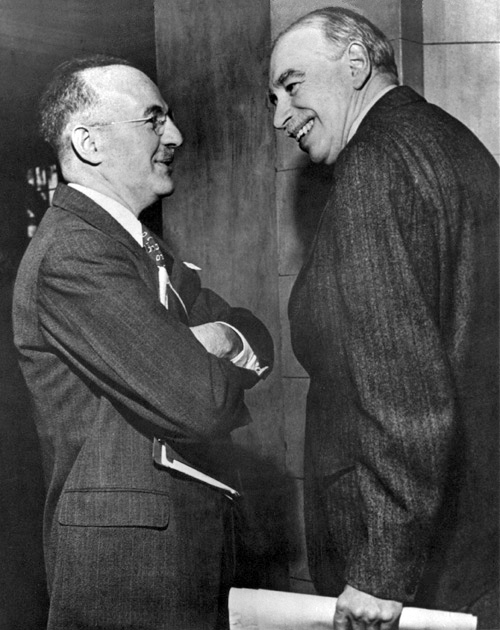

Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF, gave the annual BBC Dimbleby Lecture last week, the full text of which is available on the IMF website here. Titled “A New Multilateralism for the 21st Century”, it’s a characteristically intelligent and clear survey of globalisation and the problems facing the world: demographics, environmental degradation and inequality. She appeals to the ethos of 1944 over 1914 (it is the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I this July). She suggests that the leaders who created the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates linked to the dollar at a conference in New Hampshire in 1944 were looking beyond narrow national self interest. What she aspires to is described in this section of her speech:

“I mean a financial system that serves the productive economy rather than its own purposes, where jurisdictions only seek their own advantage provided that the greater global good prevails and with a regulatory structure that is global in reach. I mean financial oversight that is effective in clamping down on excess while making sure that credit gets to where it is most needed. I also mean a financial structure in which industry takes co-responsibility for the integrity of the system as a whole, where culture is taken as seriously as capital, and where the ethos is to serve rather than rule the real economy.”

We can all only agree with this goal. But was 1944 a matter of ethos and principle? And could it serve as guide for today’s leaders? I’m doubtful on both points.

The real lessons of 1944

The Bretton Woods system was the only time that an international financial system was actually designed from scratch, though it took several years for all the advanced economies to fully join. It followed the gold standard system of the nineteenth century, which evolved and developed around the central role of the City of London and the British economy. There was never a blueprint or treaty for the gold standard, countries simply linked their currencies to gold because they thought it beneficial and accepted the limitations on their freedom of action.

The gold standard lasted until World War 1. During the inter-war period the UK was no longer financially strong and struggled to revive the gold standard system. But the US was focused on domestic economic problems – the great depression – and there was no leadership and from 1931 no system. International trade fell sharply and the very high level of financial globalisation seen before World War I was sharply reversed.

But in 1944, with victory in Europe and to a lesser extent Japan, assured, the Allies, led by the US, were in a position to learn from the past and put in place a system that would encourage international trade while providing what economists call an anchor – the US dollar, the value of which would be linked once again to the price of gold.

This was a situation when there were collective gains from action. Purely individualistic behaviour is often inefficient and self defeating. Agreement on new rules of international finance and world trade was likely to boost economic growth and prosperity for all the parts of the world economy which joined in (the Communist nations stayed out – see endnote about China’s position). But it still required one nation to enforce the rules. There were plenty of different ways a system might be designed and no consensus on some important questions such as the role of what became the IMF and the extent to which access to global liquidity (international means of payment) should be centralised or not.

The result was without question a solution that was imposed by the US, against fierce opposition from the UK in particular. Each technical decision contained potential advantages and costs to invdividual countries, which made the negotiations something more than a technocratic symposium. But the US was in such a mighty position economically and financially at the end of World War II that it could dictate terms. The Bretton Woods system undoubtedly contributed to the long period of global economic growth from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. But it also entrenched what a French Finance Minister would later call the US dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” as the world’s key currency. International trade and payments were dominated by dollars and the US was in the happy position (as it still is) of being able to pay for imports and settle its international debts with currency that it could, if it chose, simply create from nothing.

One strand of international relations theory, realism, argues that countries simply follow their national interest. This might be a little extreme. The leaders and peoples of nations do have values and principles and can act in ways that are tangential to their interests, though rarely in direct conflict with them (assuming of course, that those interests can be well defined and agreed). The US was generous in the financial support it gave the UK and other countries during World War II, before the US entered the war, in a system called Lend-Lease. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill described this as the “most unsordid act in history”. Churchill’s quotation is often misattributed to describing the later US generosity in the Marshall Plan to provide aid to war-damaged Europe.

Both Lend-Lease and the Marshall Plan had domestic US critics yet each can be seen as in part furthering US national interests. But the scale of resource transfer to other countries can only be seen as generosity beyond mere realism. The Bretton Woods system, however, was mainly a matter of realism, or perhaps enlightened self interest. The US certainly wanted a bouyant and stable international economy and that required a credible financial system. But the US rejected limits on its power or constraints from an independent IMF (where the US still has a de facto veto on all decisions).

The problem in 2014

So what does all this mean for leaders today, struggling to find a solution to the instability of the international financial system with its frequent crises, lurching exchange rates and massive financial imbalances between the US and other countries? A multilateral ethos is certainly needed but the biggest obstacle is the lack of a dominant nation like the US. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because of the inherent tension between what was good for the US and what was needed to keep the dollar as a credible anchor. The value of the dollar could only be maintained by the US curbing the creation of dollars, meaning Congress would need to cut its spending. Faced with the choice between domestic and global interests the US unsurprisingly went for the former. We hear a similar complaint today following the testimony before Congress of Janet Yellen, the new Chair of the Federal Reserve, making it clear that she would run US monetary policy in line with what she judges to be good for the US, not for the rest of the world.

The US, while still highly influential in international finance, can no longer take the burden of backstopping the system. But neither can any other country. China may become the world’s biggest economy during the next decade but its financial system is much smaller and less developed than that of the US. Nor does it have the domestic rule of law and strong institutions that even today create trust in the dollar as a place for foreigners – including China of course – to place their reserves. While the renminbi is likely to take a much larger share of international trade and payments in future, it’s less likely to supplant the dollar as a reserve currency. But neither is the Euro, until the problems of the Eurozone are decisively fixed, which does not appear imminent.

So we are stuck with the remnants of the old system and the continuing privilege of the US in the global acceptance of the dollar, but without any commitment from the US to try to run the overall system in a way that benefits everyone. No other country can for the foreseeable future step into that role. So we will need something more than the ethos of 1944 to make progress on a new global financial system. We will need a new form of international governance with shared sovereignty. Even to state that is to make clear how unrealistic it is. Can you imagine the US, currently in one of its more isolationist moods, sharing power with a world government or global central bank? And even more implausibly, can you imagine China doing so?

*

Endnote: China and the IMF

China was a founding member of the IMF in 1945. After the Chinese Communist revolution and founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 the seat on the IMF was held by Taiwan, the Republic of China, what the PRC refers to as Taiwan, Province of China. In 1980, after the US officially recognised the PRC instead of the RoC, Beijing took over the IMF seat.

Further reading

Exorbitant Privilege Barry Eichengreen, 2011 (see a review in The Economist)

The Dollar Trap Eswar Prasad, 2014 (FT review here)

Earlier blogs:

The international financial system isn’t going to be reformed any time soon

The international impact of abolishing China’s capital controls

The once and future king? The IMF

Internationalisation of the RMB: what does that mean?

Leave a Reply