A phrase that pops up regularly in Chinese financial and economic commentary is the internationalisation of the RMB (renminbi – the people’s currency). What does this actually mean? Internationalisation is not an official or recognised economics term but China uses it to convey what economists would term a move to currency “full convertibility”. What does THAT mean?

Main functions of money

Money has three main functions:

- a store of value – if you temporarily have a surplus of income over spending you can keep it relatively safely and conveniently in money (as opposed to bags of wheat or non-transferable IOUs signed by your creditors)

- a medium of exchange – instead of having to do bilateral trades (barter) between a hairdresser and a farmer for example, you can turn use money to pay for any transaction and avoid the need for “double coincidence of wants”; this was one of the most important developments in civilisation as it allows a huge expansion of economic activity and specialisation

- a unit of account – a haircut is say £10, a kg of apples is £2; again a very valuable function.

These are functions applicable to any group of people who have economic relations with each other. These could be across national boundaries but at that point the question arises, what if two countries use different types of money or currencies? Historically it was often the case that different countries used the same currency (including gold, universally recognised). But there is great value and national prestige in issuing a currency so most countries will have their own currency. What happens at the border?

International trade and finance

A Brazilian iron ore producer wants to sell to China. They use different currencies, so they have the following options:

- the Brazilian accepts payment in RMB

- the Chinese importer somehow acquires Real to pay with

- they use a mutually acceptable third party currency, almost certainly the dollar.

The dollar is a so-called “key” currency. It fulfills at the international level the three functions of money described at the beginning. Nobody is obliged to use it but it’s convenient, partly because it is already widely used. Some commodities, such as oil, are actually priced in dollars, even by countries entirely separate from (even hostile to) the USA. In the nineteenth century commodities were often priced in pounds.

But the dollar is only acceptable if it’s regarded as reasonably stable and likely to retain its future value. Neither of these are quite so true now. But the Euro is not much of an alternative so about three quarters of international trade is still settled in dollars.

Returning to the Brazil/China case, option 1 was until a few years ago not feasible (illegal in fact). The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) restricted the use of the RMB outside the Chinese domestic economy. Why do this? To control the exchange rate and more generally keep control of the domestic financial system.

Two extremes: full convertibility and prohibition of international use

The US dollar, pound sterling and Euro are all fully convertible. That means there are virtually no restrictions on citizens of those countries buying and selling their currencies in exchange for other convertible currencies. (The only exceptions are owing to anti-money laundering rules). There is a free market in pound/dollar exchange. The price, or exchange rate – the ratio of how many dollars a pound will buy – is set by demand and supply and is constantly changing, in one of the most liquid and efficient financial markets. (It’s known as “cable” still, from the days when the telegram first linked the London and New York markets, dramatically improving the efficiency of dollar/pound exchange). The supply of dollars and pounds is set by the Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of England respectively. They target the short term interest rate in each case but do not target the exchange rate, though they may take that into account in judging whether the interest rate is at the right level to hit their inflation targets. Both have foreign reserves but virtually never use them to intervene in the market. In the US formal responsibility for exchange rate policy lies with the Treasury, but that makes little practical difference. US presidents routinely assert that their policy is a strong dollar but this is empty rhetoric. They do nothing to influence the dollar, least of all by telling the Fed to buy or sell dollars in the foreign exchange market.

The PBOC is almost the opposite case. Until a few years ago it was illegal to take physical Yuan notes out of the country and in theory nobody could hold RMB outside the territory of the People’s Republic of China. If you wanted to buy RMB for use as a tourist you bought them when you entered the country and sold any remaining on exit. Many countries have had this policy and many still do. It means they are preventing any legal foreign exchange market from operating, so the central bank can control the exchange rate. Illegal (or black) markets are hard to prevent, even with very drastic penalties (including death in the former Soviet Union and in the past in China).

Internationalisation of the RMB

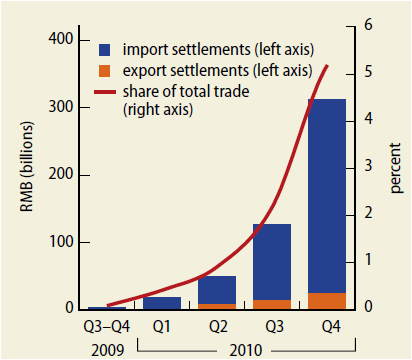

The PBOC, under instructions from the Chinese government, has gradually been moving in the direction of convertibility in the last few years. This has taken the form of permitting the use of RMB outside China for various transactions. RMB can now be used to settle trade with foreign counterparties. So a Chinese importer can buy RMB from the PBOC and use it pay an exporter, if that exporter is willing to hold it. Here is a chart from a recent World Bank/Chinese government report (China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High-Income Society):

A number of foreign central banks are now allowed to hold RMB as reserves, i.e. they can use it as a long term store of value in preference to dollars, pounds or euros. RMB can be deposited outside mainland China in Hong Kong-based bank accounts, where they can increasingly be used to buy Chinese domestic financial assets such as shares or bonds, and companies can raise RMB finance in that market separately from the domestic Shanghai/Shenzhen market (“dim sum” bonds).

RMB held outside China are gradually coming to resemble eurodollars: surplus dollars held by the Soviet Union in the 1960s were deposited in banks in London, for fear that they might be frozen by the US if deposited in New York. That pool of offshore dollars was lent to dollar borrowers, entirely outside the regulatory control of the US authorities. The eurocurrency and eurobond markets are now enormous (and nothing to do with the Euro currency, confusingly) but contribute to the ready acceptance and international liquidity of the dollar as a key currency. The same could happen to the RMB. Full convertibility would mean the end of any significant distinction between domestic and international transactions, just one integrated financial and capital market, as in London.

So there are increasing flows of RMB into and out of China, involving other currencies. In other words a growing foreign exchange market. That means, like any other market, that there is a price set by demand and supply (including speculative flows based on anticipation of whether the RMB will rise or fall in value against other currencies). If that price/exchange rate is not to the liking of the PBOC they can intervene in the market to “manage” it. So current policy is that the RMB is floating but it is what economists call a “dirty” float, compared with the clean float of the dollar or euro.

If the process of gradually liberalising the use of RMB in cross-border and offshore transactions continues, the ultimate end point would be full convertibility like the dollar. At this point the PBOC would be allowing the market to determine the RMB exchange rate and it would allow Chinese residents to transfer funds out of China at will. This would be a fairly dramatic move away from the status quo. China’s financial system is still heavily controlled by the government, particularly through its ownership and direction of the state banks. Those banks have borrowing and lending rates set by the PBOC, though with some degree of discretion at the margin. Deposit rates have for several years been lower than inflation. Having few other options for their savings, Chinese households are forced to accept negative real rates of interest, which form a subsidy to the banks (“financial repression”). Some of that subsidy is passed on in low lending rates to state enterprises and provincial governments, some goes to boosting the banks’ profits.

This control would be impossible with a fully liberalised RMB. Unattractive rates in China would lead residents to invest abroad, buying mutual funds or directly purchasing foreign financial assets. Foreigners would put money into China in the opposite direction but low rates would discourage them. Interest rates would become set by the market, alongside the exchange rate.

A fundamental principle of international macroeconomics is that, if you remove barriers to capital flows into and out of your country, you can control either the exchange rate or the interest rate, but not both. The PBOC would, in this future convertability scenario, be able to run an independent interest rate policy like the Fed, Bank of England or European Central Bank, but only if it was willing to let the market determine entirely the RMB exchange rate. It would presumably use the interest rate to target inflation, as in those other countries, though it could still intervene to influence the path of lending across the economy and subsidise/penalise the interest rate for particular sectors. But not by much. An international RMB means a Chinese financial system that is much more integrated into the world financial system.

Costs and benefits of internationalisation

The financial crises in Asia in the late 1990s and in the US and other rich countries in 2007-09 have undermined the previous economics conventional wisdom that a fully liberalised financial system is a good thing. The main benefit of some liberalisation is that China’s economy is grossly distorted by the current interventionist policy, as stated by the Chinese government itself, using the word “imbalances”. The economy would be more efficient and there would be less of a bias towards investment over consumption, if there was a more liberalised financial system in which borrowing and lending rates were not distorted by government policy. The banks would lose some of their easy profits but should be able to more than offset this by huge growth in other financial services such as personal loans, credit cards, pensions and mutual funds. The growing Chinese middle class will likely want these products just like in other countries.

The RMB exchange rate has been held down for years in order to protect Chinese manufacturing competitiveness and jobs in southern China. This is itself a distortion to the economy and no longer needed. China is far less dependent on exports now. Its growth in future will come from domestic demand, including a rebalancing towards consumption from investment. One mechanism for achieving this is a higher RMB exchange rate. This automatically reduces the cost of imports (but raises the price of China’s exports). That helps Chinese households afford more and the pressure on exporters forces them to become more competitive and move away from low value added assembly towards more complex and higher value added goods and services. All of this is in line with Chinese policy, as well as addressing the long standing complaints of the US government.

The wider benefits of a fully convertible RMB are both economic and political. China would be able to borrow in its own currency and, like the US, avoid the risk of a currency mismatch or default on its debt. The US will never actually default on its dollar debt because it can always create more dollars at will. (It could quite easily do a “soft default” by paying back in inflation-devalued dollars, so there is still a risk for foreign creditors like China.)

Politically there is great symbolism in owning a reserve or key currency. It would emphasise the importance of China’s role in the world economy and strengthen further the case for a much larger Chinese say in the IMF and World Bank.

But giving up state control of the financial system will be a big wrench. The two factions in Chinese politics are broadly in favour of this liberalisation and against it respectively. Any financial or economic crisis that appears to discredit liberalisation will provide ammunition for the conservatives who wish to stop or even reverse the withdrawal of state control.

When?

The report by the World Bank and the Chinese authorities mentioned above noted (page 63) that it took about twenty years for countries to liberalise fully their international finances after the collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in the early 1970s (a system that depended on international capital controls). I have asked Chinese bankers in Cambridge what they think about all of this. On one occasion I asked two groups from the same bank the same question: how long before full internationalisation of the RMB. I got two answers:

- it will happen really quite quickly

- it will happen, but not for a long time.

When I asked them to quantify these time periods, both groups gave the same answer: ten years.

Leading international economist Barry Eichengreen on the steps towards the RMB becoming a reserve currency: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/can-china-have-an-international-reserve-currency-by-barry-eichengreen

Aytac Aydogan

Very explanatory and contentful article; thank you…

Just a small addition; I believe that without a proper bond market and liberalised interest rates in China, the internationalisation prcess of Renminbi may be interrupted at certain steps over the stated next 10 years.

Additionally, it is going to be very interesting to see how far the Chinese government will let the Renminbi appreciate at the expense of the exporters.

Regards.

Tanuj Sharma

Simon,

Very nice explanation, even a novice reader can understand the crux of topic, which otherwise is pretty difficult to comprehend in economics subject write-ups.

Regards

Tanuj