As we commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, which marked the point where the US financial system truly moved into crisis, it’s worth reviewing the innovations that led to the real estate bubble that lay behind Lehman’s (and Bear Stearns’) problems: the separation of mortgage origination from who owned the debt; securitisation; and tranched/structured credit. Each had its merits and served a useful purpose. But in combination, and fuelled by low interest rates, weak regulation and bad risk management, they contributed to a real estate asset bubble, the bursting of which brought on both a recession and a banking crisis, made worse by the way those assets were funded (the shadow banking system).

*

Financial innovations can be new products or new processes. Three innovations lay behind the US real estate bubble which burst in 2007-08, all emerging in relation to the needs of customers or of policymakers.

1. Originate and distribute mortgage lending

The first was the originate and distribute mortgage system. Traditionally a mortgage was a long term (30 years in the US, 25 years in some other countries) fixed interest rate loan made to individuals or companies, secured on a piece of real estate that the customer purchased with the loan. The debt would be typically 75-90% of the value of the asset, meaning that the customer needed to find 10-25% of the value with their own equity. This is relatively high leverage but since real estate is a good form of collateral (it’s tangible, ownership rights are usually very clear, and the asset can be sold relatively easily) banks are happy to lend these high amounts. Mortgages allow many households to buy homes that would otherwise be unaffordable, and have helped the US reach a high level of home ownership, which peaked at 69% in 2004 before falling to about 64% in 2018.

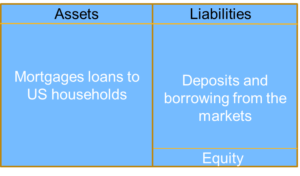

A simplified bank balance sheet is shown below. A balance sheet can be thought of showing how an organisation raises funds (its liabilities) and then what it does with those funds (its assets). A commercial bank raises funds from depositors and from issuing bonds to the markets, and uses the proceeds to make loans to customers.

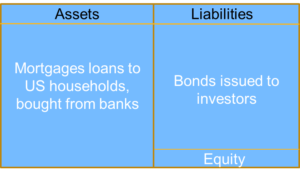

The Federal government owned housing finance institution Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) was created in 1938 to provide a boost to funding for mortgages, as part of a range of polices to boost the economy and repair a broken financial system, known as the New Deal. Fannie Mae didn’t lend to households but instead bought mortgages from banks which originated them, thus providing a secondary market. Banks could therefore make a profit by originating a loan then selling it on to Fannie Mae, using the recycled funds to make new, profitable mortgages). Fannie Mae put restrictions on the type of loans it would make, to maintain a good credit quality, but the policy was effective in raising mortgage ownership among the American people. Fannie Mae financed its purchase of the mortgages by issuing debt securities which were seen as very high quality, nearly as good as the government itself, so the interest rate was low. This low borrowing cost amounted to financial support for the whole mortgage industry, as the government intended, allowing more and cheaper mortgages to be issued by banks. Fannie Mae’s simplified balance sheet is shown below.

2. Securitisation

Separating the origination of mortgages from their ultimate ownership was a first step, but the second more radical step was for Fannie Mae to package the mortgages into new securities and sell them on to new owners, a process called securitisation. The benefit of this was that it brought additional funds into the mortgage market, from investors such as pension funds and insurance companies which previously had no way of lending for real estate, despite this being the largest type of financial asset in the US. All else being equal, more funds means a lower borrowing rate for home buyers.

Securitisation can be applied to any reasonably predictable type of cashflow and has been around in various forms for centuries. But it really took off in the mortgage market in the early 1970s. There is a potential advantage to putting a large number of mortgages into a single pool and then issuing securities backed by those mortgages, namely portfolio diversification. Historically, prudent lending meant that home (“retail”) mortgages were relatively low risk loans but there was still some risk, including from local economic setbacks that might put people out of work and make them unable to afford payments. Creating a geographically diversified pool meant that the average risk of default was lower. This meant the securities backed by mortgages, known as Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), were appealing to investors seeking low risks.

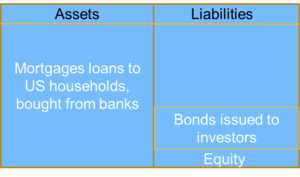

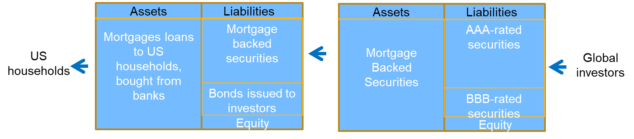

Fannie Mae’s simplified balance sheet now looked like this.

Fannie Mae and its close cousin Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) pioneered mortgage securitisation, which quickly spread to the private sector (there is a very readable account of how investment bank Salomon Brothers pioneered this product in Michael Lewis’s classic book Liars Poker, which I still highly recommend). For many years Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac dominated the supply of securitised mortgages. But the explosive growth of mortgages to lower quality (sub-prime) borrowers in the period from 2003-2007 was carried out by the investment banks, which found it was a wonderfully profitable business, particularly when combined with structured credit in the form of CDOs (see below).

3. Structured credit

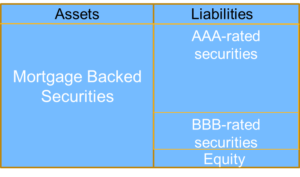

MBS could be bought like any other debt security and found a role in institutional investor portfolios. But a third innovation extended the creation of MBS in a way that met a growing demand for high quality credit risk securities, especially those rated AAA by the rating agencies. This was the idea of structured or tranched credit. To securitise any set of cashflows you need to create a company whose purpose is only to transfer one set of cashflows into another, a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). An SPV which securities mortgages buys mortgages from one or more banks (these are its assets) and finances those purchases by issuing new securities, the MBS (which are the SPV’s liabilities). Like any company, there is also some equity, representing the ownership interest of the organisation which set up the SPV. Securitisation must somehow add value: cash in is the same as cash out, so how can the SPV do this? The combination of portfolio diversification (done with more or less skill by the SPV owner and manager) and the fact of making the mortgage cashflows available to non-bank investors both represent sources of value.

Structured credit uses a further SPV to add additional value, by dividing up the securities into different risk categories. Many institutions are either legally or by their own rules required to buy only the highest quality credit risk securities, those rated AAA. This creates a particular demand for AAA securities. By the late 1990s there were very few companies or even countries in the world still issuing AAA securities, because the cost of maintaining a very strong balance sheet was not worth it to most companies, who believed they were maximising shareholder value (their chief goal) by having a good but not excellent credit rating, such as A. So there was a worldwide shortage of low-risk assets. What’s more, the fall in long term US interest rates that was driven in part by the demand from foreign central banks in Asia, especially China, meant that private investors such as pension funds and insurance companies faced very poor interest rates on the remaining pool of AAA bonds, which mainly consisted of US government bonds and those of Fannie Mae and related institutions which had a de facto US government guarantee.

Structured credit allowed the creation of new AAA assets to meet this growing demand from institutional investors for a safe asset with a slightly better return than US government bonds. How? The SPV bought a package of MBS (recall that each MBS is itself a security backed by a diversified portfolio of mortgages). These were the SPV’s assets. The SPV then issued three types of security, differentiated by their place in the pecking order of receiving cashflows from the MBS. The first class of securities were given priority – they got paid out of any MBS cashflows and were therefore very secure and safe, and the rating agencies were happy to designation these as AAA. A second group of securities would be graded as somewhat higher risk, since they only received cashflows after the AAA tranche was fully paid, but they were still fairly safe given that mortgages were historically pretty safe underlying assets. These might be graded as BBB, which is at the lower end of investment grade but still respectable. Finally there would be equity securities, representing the risk that there might be insufficient MBS cashflows to pay for more than the AAA and BBB securities. So equity shareholders took the risk, for which they expected a higher yield to compensate. The balance sheet of a CDO is shown below.

The beauty of this scheme was that even if the MBS securities themselves were not AAA-rated, a pool of them combined in an SPV might yield up to 70% securities by value which were AAA-rated. This apparent financial alchemy rested on the portfolio diversification process and on the underlying quality of the mortgages. By creating new securities for which there was ample demand, it led to new funding for the mortgage market. This of course mean that mortgage lending rates were lower than they would otherwise be. These structured credit SPVs, which were known as Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs), were very profitable for the banks and investment banks which set them up. Eventually these banks were deliberately trying to create new mortgages to feed the need for new CDOs. At that point the financing was driving the mortgage market and the system entered its explosive growth phase leading to inevitable collapse.

The chain of finance

With the three innovations in action, the de facto chain of mortgage financing now went from the investors in CDO securities (who might be German insurance companies or Japanese pension funds) to ordinary American households. By bringing international finance into a previously domestic market, the average cost of mortgage borrowing was reduced, to the benefit of home owners. It also gave foreign investors access to a major new credit class, allowing them to diversify their portfolios, which in general is a good thing. The flow of funds is summarised below.

But it also had an unintended result that would be critical in the financial crisis. Any problem with US borrowing would now affect not just American banks, but financial institutions all over the world. A US real estate crisis, however it may have started, would become a global financial problem.

Conclusion: financial innovation can have unintended consequences

Each innovation had a purpose that was in principle benign and useful. But in combination, they created a machine which took a relatively normal real estate boom and turned into a mechanism for generating very risky loans. Historically mortgages had low default rates but that was when credit was restricted to safe borrowers, interest rates were stable and recessions rare. By the mid-2000s new mortgage loans were dominated by very un-creditworthy borrowers and the pool of mortgages in the MBS and CDO was of rapidly deteriorating quality. The statistical assumptions based on the past were no longer an accurate guide to the future and the models therefore failed to predict that far more mortgages would default than before. This started to become clear in 2005 and by 2007 it was too late, housing prices were falling and many supposedly safe AAA securities were in fact not very safe at all.

FURTHER READING

The monster returns? The revival of the CDO

“Understanding the securitisation of subprime mortgage credit” Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2008 (detailed analysis of how its done, written before the full scale of the crisis had become clear)

“Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World” Adam Tooze, 2018 (very good but very long history and analysis of the whole crisis)

Leave a Reply