Africa’s economic potential is usually thought to lie in its natural resources. But the continent’s people may be its greatest strength.

One of the few areas where long term forecasts have some value is demography, the study of population size and structure. The dynamics of population growth depend on a few variables – the current population, the birth rate and the death rate – which are relatively stable and predictable. Apart from wars, famines and epidemics, all unfortunately too well known in parts of Africa, these factors determine the future of the population for decades to come. So long term population forecasts are worth taking seriously.

Population is obviously a resource but it is the population age structure that is particularly important. In any economy the population divides into the productive and the dependent. The second group is made up of children and the retired. A high proportion of productive population to dependent is good, all else being equal. Many countries have gone through a stage of fast population growth followed by deceleration. The death rate falls first and then, after a lag, the birth rate, which means that there is a “bulge” of people who start out young (when they are net users of resource) but eventually reach working age, when they are net contributors (so long as they’re not unemployed). This process is known as the demographic transition and it provides an automatic boost to a country’s economic potential, though it is not enough on its own to generate economic prosperity.

Older, advanced economies went through the demographic transition in the twentieth century. They now face a different transition, in which the death rate is still falling and the birth rate is falling to very low levels, below the replacement rate of 2.1 in most prosperous countries. Japan and Eastern Europe including Russia are below 1.5. The US is an exception at about 2 and it has more net immigration that most other rich countries.This explains why the UN forecasts the US to be the fourth most populous country in 2100 at 462m, behind India (1,547m), China (1,086m) and Nigeria (914m). The only other rich country in the top ten in 2100 is Japan at 84m, down from 127m now. Russia is forecast to shrink to 102m from its current 143m.

The rich countries face a falling working age population and a higher dependency ratio as people live longer. Health care costs are disproportionately high for older people so this process is a serious challenge to rich country economics in the next twenty years (and is already a problem in Japan, which has the oldest population).

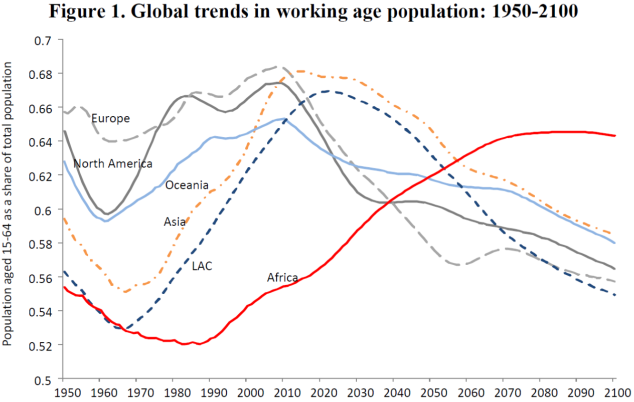

Africa is one of the last major parts of the world economy to go through the demographic transition. A recent IMF working paper (Africa Rising: Harnessing the Demographic Dividend) shows that Africa has a large rise in its working population to look forward to during this century. Eighty percent of the rise in global population to 2100 will come from Africa (most of the rest will come from India and the USA). Figure 1 from the report shows how other regions are seeing or soon will see a fall in working population relative to the total. Africa’s is growing and should grow for most of the rest of the century before reaching a generation-long plateau. Africa will be the “young” continent well into the next century. The UN forecasts that the youngest nation in 2100 will be Zambia, with an average age of 28 (it’s currently Niger at 15; the forecast oldest country in 2100 is Singapore, with an average age of 56).

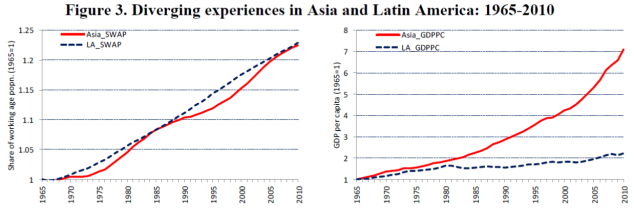

Economic growth depends on many things other than population though. Figure 3 from the report shows that Asia and Latin America had a broadly similar demographic transition from the mid-1960s to the present. But the growth of GDP per capita was far higher in Asia, which is only partly because it started from a much lower base. Latin America was, and still is, mainly made up of middle-income countries, whereas Asia in 1965 was mainly very poor. And Asia’s average experience obscures some quite large differences. China’s population growth rate has been very low and is now zero, partly owing to the government’s one child policy. The United Nations World Population Prospects forecasts that China’s population will stabilise at its current level of about 1.3 billion till 2050 then shrink to about 1.1 billion by 2100. India, the other large Asian population, will see its population grow for decades to come, overtaking China around 2028. China has had much faster economic growth than India in the last thirty years so it is now a middle income country. Rising prosperity tends to reduce the fertility rate (the level of female education is another major determinant, also higher in China than India) so China’s demographic future is now quite different from that of India.

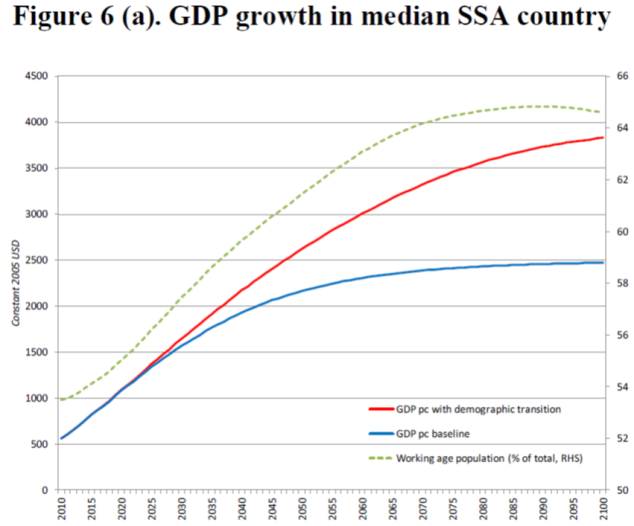

The population growth is somewhat predictable, but the economic growth far less so. Nonetheless the IMF economists estimate statistically the difference to growth in sub-Saharan Africa that the demographic transition may contribute. Figure 6 (a) from the report shows the authors’ estimate that by the end of the century the level of real GDP per capita for the median country will be about $4,000, compared with $2,500 without the demographic support. This is positive, but the underlying picture is of a poor continent even a century from now. For comparison, South Asia’s average GDP per capita is currently $1,474 and the average for the OECD countries is about $38,000 (you can see more detail at the World Bank database of world development indicators).

Africa has plenty of other economic challenges to solve before it can become a moderately prosperous continent like Latin America, let alone catch up with Europe or the US. These include infrastructure, education and above all institutional reform. The IMF economists emphasise that for the demographic transition to achieve its potential there must be substantial investment in education and in job creation. A growing pool of unemployed people is the other possible result of this working population bulge. Without successful institutions that support rather than hinder growth and enterprise, extra people will not be usefully employed. But if those other reforms do happen then the extra working age people will become a valuable resource.

Miriam Gordon

In the case of Japan and other developed countries that have already benefited from their demographic transitions, does the fact that growth has stayed reasonably high despite ageing populations not suggest that the size of a countries working population is only one of many factors that could contribute to development and growth-and perhaps is a minor one in comparison to others? Apologies if I am missing an obvious answer- I have only recently become interested in Economics as a potential degree and didn’t study it at AS level.

Simon Taylor

You’re quite right that growth of working population relative to the total population is only one factor in economic growth and is neither necessary nor sufficient for growth. Human capital more broadly matters, including the quality of the population’s skills and the proportion of women in formal employment. The rest is down to what economists call total factor productivity, which is the way in which inputs (labour, capital) are combined in more productive ways. This can be faster for less developed countries because they can copy/catch up with the more developed. For more developed countries the challenge is greater, they have to find genuinely new productivity improvements to advance growth. Richer countries with low or negative population growth can still grow the total economy if they continue to find ways to improve total factor productivity. The evidence is that they can, but perhaps not at a very high rate, say 2% a year at best.

Miriam Gordon

Thank you that makes a lot more sense now.