Countries that had similar levels of economic prosperity two or three generations ago have diverged spectacularly. Getting economic growth right makes a huge difference to the lives of people. Here are two examples: The US and Argentina, and South Korea and Ghana.

I recently came across the Maddison Project website, which has estimates of long term GDP per capita for many of the world’s countries, going back to the nineteenth century in most cases and the Middle Ages for a few, though the data are sketchy. The site is named after Angus Maddison, a pioneer in the collection and estimation of world economic development data, who died in 2010. The database allowed me to calculate the divergence between countries that have often been compared in the economic development literature, as examples of what many years of higher cumulative growth can mean.

Argentina and the US

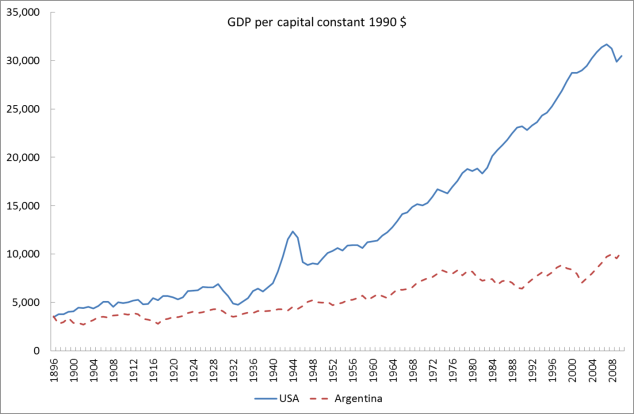

The first case is Argentina and the US, two countries with roughly the same GDP per capita in 1896. Argentina was seen then as a country of great potential, having natural resources, plenty of productive land and a good climate. It was not at all clear at the end of the nineteenth century that the US would be richer a century later. But here is what happened.

As recently as the early 1930s there wasn’t that much difference in real GDP per capita, after the US suffered the Great Depression. But the post World War II period shows the US leaving Argentina far behind. This often quoted case study in differential growth rates is usually explained by institutional differences, which have their roots in the way that land ownership evolved in the colonisation of Argentina by Spain. The book and blog Why Nations Fail describes Argentina’s elites as opting for power over prosperity. They kept exclusive institutions that penalised growth in the rest of the economy to retain the power and influence of the same old families. This is a depressingly familiar story in countries that had natural resources. It’s relatively easy to take wealth out of the ground but it doesn’t encourage the institutional development needed for broader industrial success (the rule of law, wide access to capital, a state that is not too parasitic).

Even if that’s true, the successive failure of generations of politicians in Argentina to raise their country’s prosperity is remarkable. While one can sympathise with the unfairness of the current legal battles Argentina faces in servicing its (restructured) debts, the country defaulted because of bad economic policies, which have continued. The government has expropriated people’s savings in banks, fixed the inflation statistics, grabbed ownership of the oil company YPF from Spanish company Repsol and repeatedly raided the central bank. In other words private property is insecure in Argentina. So there is little reason to think that Argentina will catch up with the US in the next generation or two.

Ghana and South Korea

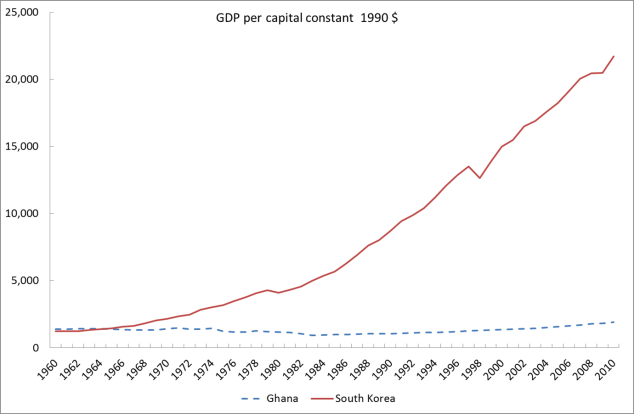

A second famous case in the economic development literature is Ghana and South Korea. In an article published on 23 September 1989 The Economist pointed out that the two countries had the same national income per head in 1957. But by 1989 South Korea’s income per head was seven times that of Ghana, which had actually fallen by nearly a quarter. In 2014 the gap is even bigger. South Korea is now a member of the OECD club of advanced economies. Ghana remains a poor nation, despite a period of optimism about growth and development in the last decade on the back of oil and gas discoveries and good economic management.

The Ghana/Korea comparison is more shocking than Argentina/US, because the divergence has been so spectacular. The lives of people in South Korea are radically different from those of their grandparents. Economic growth is not the only thing that matters in life but prosperity of this scale brings with it mass education, health and far better life prospects for the majority of people.

South Korea is not unique; it is one of several countries in east and south-east Asia which have seen remarkable economic transformations. There is no comparable African success story. The causes and roots of this difference in economic fortunes are much debated. They lie in a mixture of colonial history, geography and policy decisions. Both Ghana and South Korea have had authoritarian govenments but the Korean ones made decisions that transformed the economy rather than just redistributing the existing wealth.

Ghana remains a cause for hope in Africa, even though in August 2014 it had to ask for IMF support because of its unsustainable balance of payments deficit. The IMF’s last Article IV report in May 2014 warned of short term risks arising from the fiscal and external deficits but it also praised the achievement of “strong and broadly inclusive growth” over the previous two decades. So there is still optimism that Ghana is doing many things right and can harness its oil and gas income with less damage to the rest of the economy than has been seen in so many other African countries. Too often the state has been captured by a small elite which then steals most of the wealth for itself, which is bad enough, but this sort of state, combined with the high exchange rate caused by the resource exports, blocks other economic development, an outcome known as the “resource curse“. The IMF bailout is hopefully just a temporary setback for Ghana.

Grace Gitu

Thanks Page for this enlightment. Ghana and Argentina were colonies who gained independence after the world war II unlike US and Korea. The difference in economic growth may have arisen from:- contribution of economic activities by the colonial masters, poor support of economic development to the independent nations by the advanced economies, poor exploitation of resources, corruption, population pressure and advantage to economic competiveness. The emerging globalisation processes offers a platform for enhanced economic growth. The fastest economic growth rates are now being reported from nations which previously had very low GDP. By the way GDP may not be an accurate measure of a nation economic growth

Simon Taylor

Argentina became independent from Spain in 1816. Ghana became independent from the UK in 1957. Korea was annexed by Japan in 1910 and became independent in 1945 but divided into two. North Korea invaded in 1950 and South Korea became an independent state in 1953 after the de facto end of the Korean War. The US became independent in 1776.