I was recently asked the difference between a Ponzi scheme and a pyramid scheme. They are closely related but there is a key difference, which is that a pyramid scheme is not necessarily fraudulent, though it frequently is marketed with fraudulent claims. A pyramid scheme is closely related to any financial bubble, with the difference being that a bubble is usually not deliberately created by one individual or organisation, it is social in nature. All have a long and ignoble history, with the Madoff fraud being the latest high profile Ponzi scheme and pyramid schemes reaching something of an historic low point in the Albanian disaster of 1997.

Ponzi

A Ponzi scheme is a dishonest investment plan in which investors are paid returns out of their own capital or out of the capital of new investors. For any given amount raised this payment will eventually be exhausted, at which point the fraud will be discovered, so the fraudster must attract new funds. If the payout is not too high then the scheme can run for several years before collapsing but it must collapse eventually.

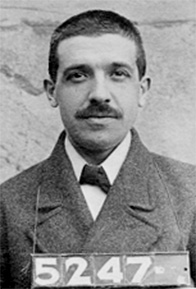

Such schemes have been around for centuries but the name is more recent. Charles Ponzi was an Italian immigrant to the United States who, after several misadventures and a spell in prison, started a legitimate scheme in 1919 to exploit an arbitrage in the pricing of international reply coupons. But he quickly moved beyond the modest profits that brought, to outright fraud. The returns to his investors were simply the incoming funds of new investors, with a generous profit for himself. In 1920 Ponzi was making $250,000 a day but the extraordinary returns (50% after just 45 days) attracted first journalist inquiries and then legal ones, motivated by the fact that the profits were out of all proportion to the number of actual international reply coupons in existence. It took several months for the truth to come out but he was eventually convicted of fraud and sent back to jail. He had a colourful life thereafter but died in poverty in Rio de Janeiro in 1949, having achieved a dubious form of immortality through his name.

Source: Wikipedia

A very basic Ponzi scheme would be this. I raise $1m in funds and promise an annual return of 10% (which in today’s low yield world would be very appealing). I will run out of money after a maximum of ten years. And since there is no point in risking prison without getting rich, I would want to extract some of the money for myself, either as a fee or by straight theft. So the scheme would last for less than ten years, even assuming nobody asked for any of their capital back. But that is quite a long time relative to a pyramid scheme.

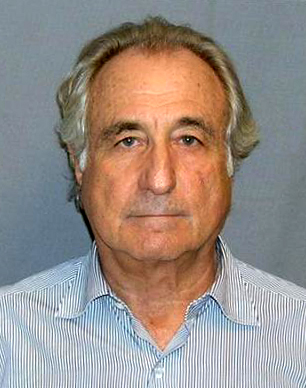

Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme was on a dramatically larger scale than that of Charles Ponzi and is the largest fraud in US history to date, with investors losing $13 billion (the even greater losses during the financial crisis were not fraudulent in a legal sense). Sentenced in 2009 to 150 years in prison, Madoff admitted running a fraudulent investment scheme from the 1990s. He had set up his investment firm in the 1960s but only went bad later on. As former chairman of NASDAQ he was widely respected in the investment world and this helped him keep his scheme running for so long. This is a common feature of Ponzi schemes: many start as legitimate and well intentioned investment ideas but when the returns disappoint the entrepreneur gives into the temptation to “temporarily” fake the numbers. But soon the relentless need for growth makes it impossible to cover up the losses with real returns and the investment becomes completely fraudulent.

Pyramids

A pyramid scheme is one in which the new investors or participants (it is not necessarily described as an investment, which it quite plainly isn’t) pay money to the founder or other people who joined the scheme earlier than them. They in turn achieve a return by attracting new members. If explained clearly it is obvious that no net wealth is created, it is simply a transfer. The pyramid concept is that of exponential growth. It is necessary for each new generation of joiners to recruit a further one that is larger than their own, or they won’t get paid. But that cannot continue indefinitely as the number of people, let alone gullible or credulous people, is finite.

Consider a simple example. The scheme promoter sells it to two people, who each pay $100 to the promoter. Each of these must in turn recruit two more people who pay $100, just to get their payment back. Those four new joiners need to recruit a total of eight new ones.. and so on. This doesn’t even make a profit but the logic of required growth is clear. Actual schemes are more complex and would involve new joiners paying to members two or three “levels” higher than them so that a member makes a profit on their payment, so long as the scheme keeps going for long enough afterwards.

It is logically impossible for the scheme to end in any way other than with a majority of members losing money. If you are an early entrant to the scheme you may make money but you don’t know for sure that you are early, because you can’t be sure it will keep going. So joining is a gamble. If there is no misrepresentation, so joiners realise there is no actual productive use to which their payments are being put, then this is not a fraud, merely a gamble. But the scheme is inherently dishonest, because from day one its liabilities exceed its assets and it is only a matter of time before it collapses.

In practice such schemes are often accompanied with a fraudulent investment scheme or otherwise misrepresented to disguise the obvious pyramid nature of the scheme, which offers returns that are too high to be earned by any plausible investment scheme. Assume a scheme in which four original members need to recruit four more each and they in turn recruit four more each. After ten iterations, the number of members required is up to 4 to the power 10, which is just over a million people. At the sixteenth generation of joiners, we need 4.3 billion people. It is therefore only a matter of time before the scheme burns out and the last generation (or possibly two or three) will lose their money.

Albania

The most spectacularly destructive scheme in history was in Albania from 1996 to 1997(*). With the end of Communism in 1992 and the transition to democracy, Albania was the poorest country in Europe, with a very limited banking system and ineffective regulation. Deposit taking companies offered high returns and grew quickly at a time when there were few other investment opportunities and the population was poorly educated in finance. Critically for what followed, members of the government supported and endorsed the companies, which turned out to be pyramid operators. Some started with real investments, and others were widely believed to be making money from smuggling into the former Yugoslavia (where UN sanctions were in force). But all eventually became pure pyramid schemes.

Two things distinguish the Albanian pyramid schemes (there were several companies). The first was their size. Nearly two million people out of a population of three and a half million were investors in the schemes. The iron law of compound growth was delayed because of the very high penetration of the scheme, fuelled by money from Albanians abroad and illegal proceeds from smuggling across the UN sanctions against Yugoslavia. The IMF and World Bank repeatedly warned against the schemes but the government refused to condemn them until it was too late. The companies declared bankruptcy in January 1997 with liabilities of around $1.5 billion, in a country where the average monthly income was $80.

The second distinguishing feature was the result of the collapse of the schemes. People demanded that the government compensate them and the country descended into chaos, anarchy and near civil war. The government lost control of southern Albania and foreign nationals were evacuated. Some 2,000 people were killed. Order was restored by a United Nations force of 7,000 troops in April 1997.

Albania, which this November celebrates a century since its independence from the Ottoman Empire, is thankfully a very unusual case and has recovered remarkably well from this searing episode.

NOTE (*) My account draws heavily on Christopher Jarvis (2000) “The Rise and Fall of Albania’s Pyramid Schemes” IMF Finance and Development, March 2000, Volume 37, 1 available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2000/03/jarvis.htm. See also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ponzi_scheme

Leave a Reply