Debt rating agencies have no particular expertise or special information on sovereign debt, especially for developed economies, so their views don’t matter

*

News that Fitch downgraded the US sovereign debt rating from AAA (the highest rating) to AA+ (the next highest, and still very high in normal circumstances) has been widely featured in media commentary that suggests this could scare off investors in US government debt. Something similar happened when S&P downgraded the US from AAA in September 2011.

But markets are likely to ignore Fitch, as they ignored S&P. This is because rating agencies have no particular skill, insights or information on sovereign debt, unlike their core business of corporate debt rating.

The rating of corporate debt started in the mid-1850s with the growth of US companies issuing of bonds to investors. Recurring financial crises created a demand for somebody to provide objective analysis of these bonds, and out of those early beginnings the modern credit rating agencies were born.

These agencies have thorough processes, a great deal of data and, crucially, access to management of the companies which pay for the rating (note that the investors who use these ratings do not pay for them). While today’s investment banks and credit investment experts can pretty much replicate the processes and data, they lack the specialist information that the rating agencies get from the companies, which provides a small edge to those agencies. So their opinions (and they are very clear that their ratings are no more than that, partly for legal protection) have value to investors. And indeed they have some value in predicting defaults.

The rating agencies’ reputations were badly tarnished by their profitable excursion into rating complex, structured securities such as Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs), in the lead up to the US financial crisis of 2008. Setting aside allegations of the profit motive corrupting their processes, the real problem was that the rating agencies had no particular expertise in this area, which was largely about auditing the structure, but not the underlying creditworthiness, of mortgage backed securities-based portfolios. Investors in those CDOs seemed not to realise that the rating agencies had not in fact checked whether the sub-prime loan to Mrs. Smith of Main Street, Pasadena, California was likely to be repaid; the agencies merely offered an opinion on the probability of default, given a set of assumptions provided by the structurer of the securities, usually an investment bank.

Sovereign credit is rather different from corporate credit. The ability of a corporation to pay its debts is pretty clearly defined: it either has the cash or it hasn’t. If it can’t quickly obtain cash, by selling assets or some other legal process, then it’s in default. A variety of stock and flow measures, combined with a more subjective assessment of the company’s management and strategy, underpins the rating.

But a country’s point of default is more of a political choice. It is rare for a country literally to run out of resources to pay its debts, though Sri Lanka’s default in April 2022 comes close. Governments have some discretion as to when they decide, enough is enough, we can’t extract the resources from our economy to keep paying the debt. This is obviously in part a political judgement: the political cost of the default has to be less than the political cost of continuing to tax or borrow of sell off state assets.

Rating agencies use a range of macroeconomic measures to assess the risk of default: the level of foreign exchange reserves, the balance of payments outlook, the state budget position and so on. But they, and anyone else trying to gauge the risk of default, must assess the politics, including the probability of help from a friendly nation. Diplomatic considerations may apply: the US has historically helped out certain nations in distress, some wealthy Middle East governments have provided emergency lending to favoured countries and so on.

The US is in the happy position of being able to borrow in its own currency, so that in a trivial sense it need never default, though if it pays its bills by just printing money, the repayments will be in increasingly devalued dollars (this is sometimes called a “soft” default). For most countries, including unlucky Sri Lanka, servicing foreign debt means using foreign exchange that comes from net exports. Once you’ve run out of foreign exchange reserves, you must either export more or import less. But when imports include fuel and food, the choice of whether to keep paying foreign creditors or starve your people is a miserable one. The point where the pain becomes unbearable, and default follows, is not predictable.

There is no simple, objective way of assessing these matters. I mean no disrespect to the fine people of Fitch, S&P and other rating agencies when I say that they simply have no particular ability to do this better than many other third parties. For US government debt, the most widely held in the world, there are thousands of actual and prospective investors, all having their own view of the likelihood of a default. Those views will include the outlook for US GDP growth, the prospects for reform of health and social security spending and above all the way the US political system functions, or doesn’t in future. People can in good faith have differing views on this.

There is also a parallel market in the probability of debt defaults, namely the credit default swap (CDS) market. While the depth of that market varies by the type of debt, it’s very liquid for US debt and reflects the opinions of a wide range of market participants, whose collective view is more likely to be right than that of any individual analyst.

It is true that sovereign debt ratings matter for emerging market debt, where investors do tend to rely on the rating agencies’ opinions, sometimes in the form of a specific condition in a non-sovereign debt contract. Even then, the CDS price is probably a better guide to the risk of default.

Will the US default one day?

Fitch’s explanation for the US downgrade was:

The rating downgrade of the United States reflects the expected fiscal deterioration over the next three years, a high and growing general government debt burden, and the erosion of governance relative to ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’ rated peers over the last two decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.

The first part of the explanation hinges on whether you expect a recession in the US. The conventional wisdom, that rising interest rates made this very likely, is now shifting. Indeed the US economy is in pretty good shape: the first estimate of 2023 second quarter GDP growth was 2.3%, a rate that the EU and even more the UK would kill for; unemployment remains historically low at 3.6%; and inflation is falling more quickly than consensus expected. Of course, it could all go wrong and macroeconomic forecasting is notoriously difficult.

The erosion of governance that Fitch refer to is a much more reasonable concern, but a well known one. The US Congress has repeatedly flirted with not raising the debt limit (a peculiar feature of the US system is that there are separate government votes on the budget, which is a flow measure, and the debt limit, which is a stock measure that is logically linked to the flow measure). Whether one day Congress goes over the edge is anyone’s guess.

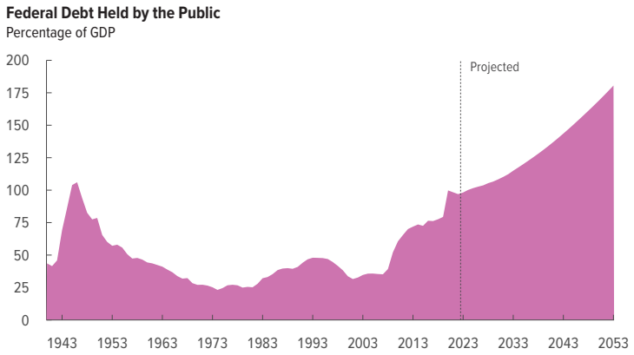

More worrying are the long term debt projections of the independent Congressional Budget Office (see below), which show exploding debt in the 2030s, assuming no rise in taxes and no reform of health spending. The US is not alone in having an unsustainable debt outlook, mainly caused by an ageing population. But the consequences matter far more because of the unique international role of US government debt in the financial system.

So Fitch may be right eventually.

Leave a Reply