Demography, the study of population, is one of the few areas of the social sciences where long term predictions (over one or more decades) can have some value. This is because the dynamics of population growth depend on the current age structure (how many young versus old people), which is fixed in the short term, and the birth and death rates, which don’t tend to change too quickly.

Of course populations can suffer large, sudden falls, as a result of war, climate change or disease. The plague known as the Black Death killed between a third and a half of the European population in the 14th century, causing a labour shortage that ended feudalism in western Europe and contributed to the new capitalist system that would later (and temporarily) make Europe the leading part of the world economy.

Less dramatically, it is widely accepted that the global population is still growing but at a falling rate, so it will peak later this century and then fall. The history of demographic change has revealed fairly strong patterns across countries. One is a fall in the death rate as nutrition, primary health care and urban sanitation improve (antibiotics and better secondary health care also help but are much less important). The birth rate similarly has fallen in most countries because of three things: improved female education; urbanisation; and higher standards of living.

Fertility is now falling pretty much everywhere but from different levels. In poorer countries where fertility is higher than average it is nonetheless falling, and seems to be falling more rapidly than it did in earlier periods in those countries where fertility is now very low.

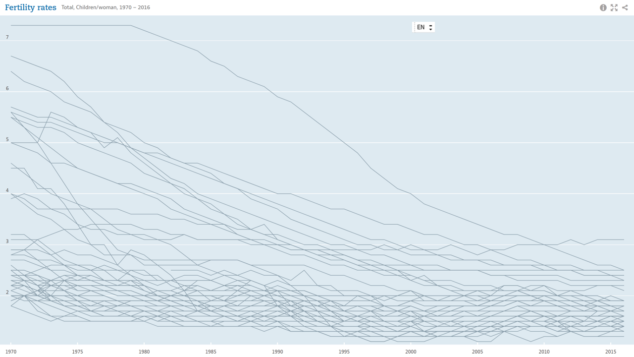

The birth rate is the number of births divided by the average population but to have consistent metrics across countries with quite different age structures, demographers use the fertility rate, which is a standardised measure where a level of 2.1 is consistent with stable population. If the fertility rate dips below 2.1, the country concerned will, sooner or later, see its population fall (unless it has net positive immigration, which turns out to make a very big difference to some countries, such as Canada). The chart below shows falling fertility rates across a selection of countries (not labelled, as it’s already a complicated slide). The line at the top which shows a huge fall from over 7 to its current level of 2.5 is Saudi Arabia. The country with the roughly flat line which rises a bit to 3.1 is Israel. But the general pattern is clear: falling fertility and a convergence to rates at or below replacement.

https://data.oecd.org/pop/fertility-rates.htm

The United Nations central projection has global population peaking at about 11.5 billion (compared with 7.7 billion now) around the end of the century. Reflecting the uncertainty even in demographic forecasts, the UN provides high and low variants. A new book, Empty Planet, argues persuasively that we are more likely to see the low variant play out, with global population peaking 2050-2070 at about 9 billion. This is because the factors driving lower fertility seem to be having a faster effect in many countries than in previous history. (The book emphasises the work of Wolfgang Lutz and his colleagues at the Wittgenstein Project in Austria which, unlike the UN, uses educational levels in their projections, something that they argue more accurately captures recent falls in fertility.)

China’s fertility rate appears to be staying low

These alternative projections are especially important for the world’s currently most populous country, China. China, the largest population country for most of human history, is just about at the point where its absolute population will start falling (it will be overtaken by India very shortly – and some think that has already happened). It is well known that China has for four decades had a lower fertility rate than other countries of similar income levels because the government imposed a one-child policy in 1979, after a near doubling of the population since the revolution of 1949. China’s birth rate fell and the population growth slowed down to the current point of about zero.

The Chinese government decided in 2016 to relax the policy to allow two children. Many analysts both inside and outside China believed that the one-child policy was a mistake because it would lead to a rapid ageing of the population, meaning that the proportion of older (retired) people to younger (working) people would rise. The decision to change the policy was a belated response to those concerns.

It was expected by many people, including the United Nations Population Projections team, that the fertility rate would rise somewhat from its low level. The central projection from 2017 is that China’s population will still shrink, from about 1.4 billion in 2019 to about 1.1 billion at the end of the century. That is a fairly big decline and would leave China having a very “old” population structure. For many years now, people have often described China’s challenge at to grow rich before it grows old (the contrast is Japan, which is the most “old” nation now but one that is already among the world’s richest).

But the data since the ending of the one-child policy show no sign of a rise in fertility. The data for 2018 suggest a fall to even lower fertility levels. Many researchers suspect that China’s high level of urbanisation (including high property costs in many cities) is reinforcing an established culture of small families to create permanently very low birth rates.

If this is true, then China’s population in 2100 may be only half its current level or even less, with a corresponding worsening of the age structure. Researchers in China are reluctant to make their conclusions too public for fear of contradicting the official line. But anecdotal evidence appears overwhelmingly to point to an entrenched low birth rate.

In traditional, rural societies, children were an asset, a source of labour to help run the farm. But in urban economies children become an economic liability – they require more space and may reduce the earning prospects of women (though this depends a lot on the country’s policies on childcare).

Nobody can be sure what the future will bring but so far it seems that no country that has seen its birth rate fall, has been able to push it back up again. That means most countries are heading for lower populations, drastically in some (Japan, South Korea, Italy and Germany for example).

We will never know how far the one-child policy reduced the birth rate below what it would have been, but China had a high level of female education and relatively good economic prospects for women, both of which would have probably caused a big fall in the birth rate in any case. The birth rate in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, admittedly more prosperous economies than mainland China, have all collapsed, without any state intervention. On the contrary, Singapore’s government is trying to get the birth rate back up again, with no evidence of success.

Southern Europe, a region traditionally thought of as Catholic and therefore inclined to larger family size, has also seen a sharp fall in fertility rates to below replacement levels. In 2015 the Italian Health Minister described Italy as “a dying country”. The country’s fertility rate is just 1.3. The population has continued to grow because of immigration, but that has become a very controversial matter in many European nations, some of which appear to prefer to see their national population decline indefinitely rather than admit immigrants.

China’s economy may not be the biggest for long

So China may have only 700m people by the end of this century. Does this matter? Clearly what matters to most people is their standard of living, which is a matter of resources per head, which need not fall just because the number of heads is falling.

But a rapidly ageing population is a problem if it means fewer people to pay for the retirement and health costs of the older generation. This might be manageable if it happens slowly but Japan, and soon China, is experiencing this shift quite fast.

Population shrinkage also means lower potential economic growth, even if it is rising per head. China’s total GDP has been confidently predicted to overtake that of the US for many years now. But it may not be ahead of the US for very long, and may in turn be overtaken by India’s which is likely to grow both because of catching up to Chinese productivity levels (something currently underway) and because India’s population will probably grow for another 20 years or so, though it too is likely to experience an earlier peak than current official forecasts suggest.

Meanwhile, the US, a country founded on immigration, should see much more rapid population growth than any other developed nation, for decades to come, even if immigration is brought to a halt (which seems unlikely). Immigrants tend to be younger so they boost the population fertility, at least for a while. The UK also has higher population growth potential because of high immigration. Canada, a country with unusually high immigration, is likely to see its population grow enormously over the rest of this century.

The US could reach 450m people by the end of this century (according to the UN forecasts; the Wittgenstein forecast for 2060 is 410m), with a level of productivity that China is unlikely to fully match even on that time scale. So it’s quite possible that the economies of China and the US won’t be all that different in size later this century. And India’s may be largest of all.

UPDATE

An article in The Lancet in October 2020 makes new forecasts that are broadly consistent with those above. The authors’ central forecast is that China’s population will fall from 1,412m in 2017 to 732m in 2100. Nigeria’s population is forecast to rise from 206m in 2017 to 791m in 2100, so a little above that of China.

Shanshan Zhang

So interesting! Apart from the reasons you gave, I believe the increasing nurturing costs and soaring fear of damaged natural environment are other two crucial factors deteriorate the birthrate in China. Put aside the potential threatening of air pollution on fertility. The age structure of population, as the post discussed, is for sure equally important as the birthrate. Forecasting population outlook especially for a long run is full of uncertainties. In the presence of genetic engineering, whether the order of the present world can still be functioning is intriguing. However, I believe the compatibility of super advanced physical quality and mental quality would take a very long time.

Simon Taylor

Agreed, China has many environmental problems that may also contribute to lower fertility, as they are in other countries.

Ravi Dharamdial

Simon, do you think countries like China, Japan and Singapore will have to review their immigration policies as means of addressing this problem?

Simon Taylor

They aren’t forced to. Many countries may prefer steady population decline to an influx of immigrants. Singapore has always had a lot of immigration (though that has been a source of some local friction in recent years, owing to rising property prices) so they already have a sensible policy from the point of view of stemming population decline. I don’t think China has any realistic chance of changing the outcome because of its sheer size. Already women are brought in from south east Asia as brides for rural men. But there aren’t enough people to make this feasible as a long term solution.