A lot of people in the richer economies appear doubtful that economic globalisation has been good for them. But there are hundreds of millions in the rest of the world for whom globalisation has been a critical part of their escape from poverty.

*

Globalisation means the greater international movement of goods and services, finance, people and ideas. The first two of these – the globalisation of trade and capital – are the ones I refer to as economic globalisation, and they are the most important in explaining why some countries have escaped from poverty in the last 50 years. Labour remains much less mobile than capital and faces a backlash in rich countries against the migration that has already happened. The internationalisation of ideas has both an economic and a cultural influence but is not (yet) as important for global economic activity.

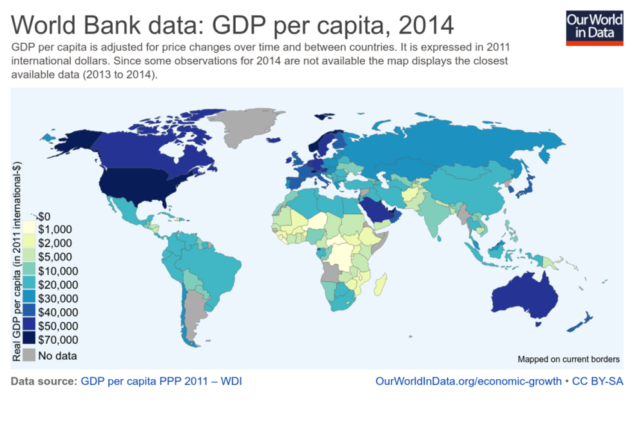

With all of its shortcomings as a measure of human welfare, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per head is the least bad guide to a country’s overall living standards and changes over time. The chart below (taken from the excellent Our World in Data website provided by the University of Oxford’s Oxford Martin School) shows the enormous variation in GDP her had across nations.

The broad picture should be familiar: the so-called advanced economies in north America, Europe, Japan and Australasia, plus a range of middle income countries in Asia and Latin America, with the lowest income countries mainly in Africa and parts of central Asia. The good news is that most of the world’s population now live in middle income countries (a broad category, with average Gross National Income (similar to GDP for most countries) of $1,000 to 12,000 according to World Bank definitions).

Country averages can be misleading: China is now an upper middle-income nation ($4,000-12,000) but can be thought of containing a still large population of rural poor (now a key target of government policies), a majority of urban dwellers with living standards close to the lower end of the advanced economies, plus a proportionately small but absolutely large (bigger than the UK population) of people living a decidedly advanced economy life style.

According to the World Bank, extreme poverty has fallen from 36% of the global population in 1990 to 10% in 2015, most of whom live in Africa. One can see this as good news (the direction of change is positive) or bad news (there is still extreme income inequality in the world and over 400m extremely poor people in Africa). I follow the late Hans Rosling’s view that things are bad but getting better.

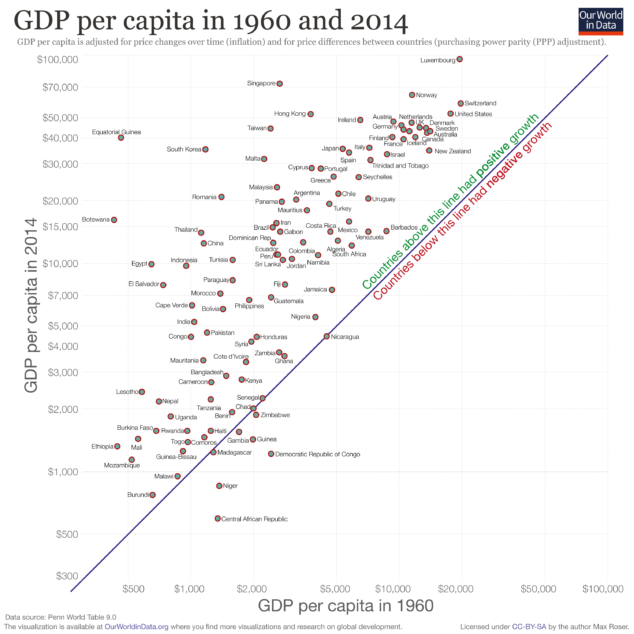

Just how much things have changed in two generations is shown in the following chart, which compares GDP per head in 1960 with 2015.

The way to read this chart is to locate countries relative to the 45 degree line. If the world economy is delivering, we should expect countries to have shown growth in GDP her head since 1960, with poorer countries doing better i.e. catching up (note that the scale is logarithmic). So if we look at the top left part of the chart, we should find lots of countries that were poor in 1960 but have boosted their incomes to that of richer economies in 2015.

Of course that part of the chart is rather empty. There are a couple of outstanding but unfortunately unrepresentative cases in Africa. Equatorial Guinea has seen a huge rise in average GDP because of oil, but the benefits have been spread very unequally, as they have in other resource-rich economies. Botswana is a rare case of successful management of natural resources (in this case diamonds), avoiding both extreme income inequality and the political damage brought by “the resource curse”.

The most impressive examples of economies moving from low to high incomes are all in Asia: Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea. Two of these are essentially cities (Singapore and Hong Kong) with very distinctive histories (for example they both inherited important legal institutions from the UK that remain critical to their economies). That leaves Taiwan and South Korea, both of which began with authoritarian political systems that drove economic development, but then evolved into democracies, though in somewhat different ways. (I wrote about South Korea’s remarkable transformation here). For those who hope that economic growth that starts with an undemocratic state will inevitably lead to democracy, the bad news is that the recent cases amount to these two, which is hardly a robust base of evidence on which to ground a general theory. (In the last couple of years there has been a belated realisation among US foreign policy analysts that China shows no sign of following the South Korean or Taiwanese path – the puzzle is why they were so confident it would do. This disillusionment lies behind the recent quite rapid change in US foreign policy elite attitudes to China, which are much more profound than President Trump’s trade war).

Lots of other countries have seen progress but it must be something of a disappointment that so many middle income nations, especially in Latin America, a continent that in 1960 was far more prosperous than most of Asia, have seen only modest progress.

How countries can become richer (and in particular how they can reduce mass poverty) is probably the most important question in economics (apart from how to fix climate change). And there is a lot of disagreement about what countries should do. But the East Asian success stories do seem to have some common themes, including: a strongly interventionist state which nonetheless ensured a role for markets; investment in human and physical capital; and,most important for our theme here, a heavy use of exports to the world economy.

For relatively small economies such as South Korea and especially Hong Kong and Taiwan, the local market is too small to provide a base for efficient manufacturing, where economies of scale tend to be important to get costs down. Beyond that, tapping into the global export market exposes companies to brutal competition and forces them to improve both costs and quality, eventually allowing a globally competitive manufacturing base to develop (Samsung, Taiwan Semiconductor). Singapore and Hong Kong long ago stopped being competitive manufacturing centres and have moved into high end services, particularly finance. South Korea and Taiwan are facing a difficult transition to either (even) more advanced manufacturing or other technology-based economic activities. They have benefited from the development of the mainland Chinese economy but now face increasing competition from that same economy.

China too built much of its economic success on accessing the global market, using what used to be its cheap labour, combined with capital from Hong Kong and overseas Chinese investors. Unlike South Korea and Hong Kong, China has its own very large market now – its access to data is unparalleled and may be a decisive advantage in the further growth of digital services.

It is difficult to imagine these economic success stories without the ability and willingness to export to the rest of the world. In that sense, the globalised economy was essential to the East Asian economic success story. It became conventional wisdom in the 1990s (known informally as the “Washington consensus” because the IMF, World Bank and US State Department are all based there) that openness to trade was a necessary condition for economic development. The evidence for this is pretty good. (The other aspect of the conventional wisdom, that globalisation of financial flows was also a good thing, is much more questionable).

But for developing economies to export their way to success, there had to be an importer, which was mainly the USA. The consequences of the USA absorbing more imports, especially from China, are now a major political issue, and form the justification for President Trump’s trade war with China.

The questions that arise from this are: i) can other countries copy the same model: and ii) did the richer countries also benefit from economic globalisation and will they continue to facilitate this globalised economic model?

(*) I am teaching an elective for the Cambridge Executive MBA in February 2019 titled “Brexit, Trump and the backlash against globalisation: why the international economic system is at risk”. This is the second of a few posts that are background reading for that course. The first post is here.

rjw

China is rather unique due to size, political system, culture and history. Also the historical conjuncture in which it made its development push (end of cold war, push for globalization in west etc). So hard to make a direct read over from the Chinese case to other economies.

That said, I don’t see why the global economy could not accommodate another export led tiger, in principle.Trade to GDP elasticities fell after the GFC, but they remain positive, and who knows what niches technological and social change may open up. But size is surely an issue.

I suspect the Indians, for example, would struggle with an export led growth model – not just because because their internal political and economic conditions are very different, but due to the sheer size of markets they would need to find to provide for a couple of decades of export led growth – particularly given the very young demographics.

Simon Taylor

Thanks for your comment. Agreed, China is exceptional in many ways, though we economists hunt for common themes across successful development stories that could, in principle, be applied in other places. I also agree that manufacturing-led export growth will be harder in future, for large economies such as India, because the rich countries are less keen to boost their imports. India may be able to grow service exports instead but they may also face similar protectionist resistance. Manufacturing has been the traditional way to modernise an economy and at the same time boost high paying jobs, but the latter part may be less relevant in a world of rapidly increasing automation. So it is harder for India and potentially harder still for the fast population growth nations of Africa.