Financial services are provided mainly in two ways: by banks and by markets. Here we outline the key features of financial markets

*

A market is a very general concept of any arrangement which brings together users for mutual advantage. We’re used to thinking about markets as mainly for goods and services but the concept is wider. For example dating sites can be thought of as markets which bring people together with the hope of finding a successful match. Similarly there are mechanisms through which graduating students apply to and are accepted by universities, medical schools and law firms. All of these are matching markets, meaning that they help to bring supply and demand together so that the users get the best “deal” they can. These markets work by matching the characteristics of the people, using some form of rule (an algorithm).

Economic markets also match demand and supply but they do it mainly through price. The demand and supply for coal, copper or Toyota cars are matched by price (though other characteristics of the product are also important). Financial markets are a special case of these markets, mainly because of their size and the frequency of trading.

Economic markets: bringing together demand and supply

A dictionary definition of a market is a regular gathering of people for the purchase and sale of goods and services. So the essential components are people and some form of organisation that lets them buy and sell. The benefit of a market is that if you want to buy something you want as many possible sellers as possible and symmetrically for sellers. Both buyers and sellers therefore gain from an arrangement that brings them together.

Traditionally that arrangement was a physical place. Agricultural markets go back thousands of years and the origin of many towns was the concentration of economic activity that was based on markets. People travelled from surrounding areas to sell their produce and buy what they couldn’t produce efficiently themselves. Markets therefore facilitate specialisation of production, the division of labour that is the basis of economic productivity.

The term market can be used more loosely to refer to the sum of demand and supply for a particular commodity or service. We talk about the Shanghai property market to mean the total of supply and demand for housing and commercial property. The participants in that market can be global, both as buyers and sellers of Shanghai apartments. They meet, if they meet at all, through agents and online. Ebay brings together buyers and sellers from all over the world, for a huge range of goods.

So a market need not be a physical place any more. So long as there is some sort of mechanism or arrangements for bringing supply and demand together we can say there is a market in place.

Financial markets are among the oldest. Moneychangers provided what we would today called foreign exchange services, in ancient times when commercial travellers crossed boundaries. There is evidence of pieces of paper being issued in exchange for the storage of agricultural produce such as grain, which were then tradable. That trade was made easier and more efficient by the presence of trader intermediaries who began to group together in a single place, a prototype financial market.

The earliest modern financial markets had a physical location in places where people naturally met for conversation and drink. Coffee shops, reflecting the newly fashionable drink of the age, flourished in the seventeenth and eighteenth century in European and American cities. One of these, Lloyds of London, evolved into the world’s leading insurance brokers. Once people come together to chat and drink coffee (or tea or chocolate) they naturally turn to trade. Although this might have been possible in a pub, the presence of alcohol is not ideal for steady and reliable commerce.

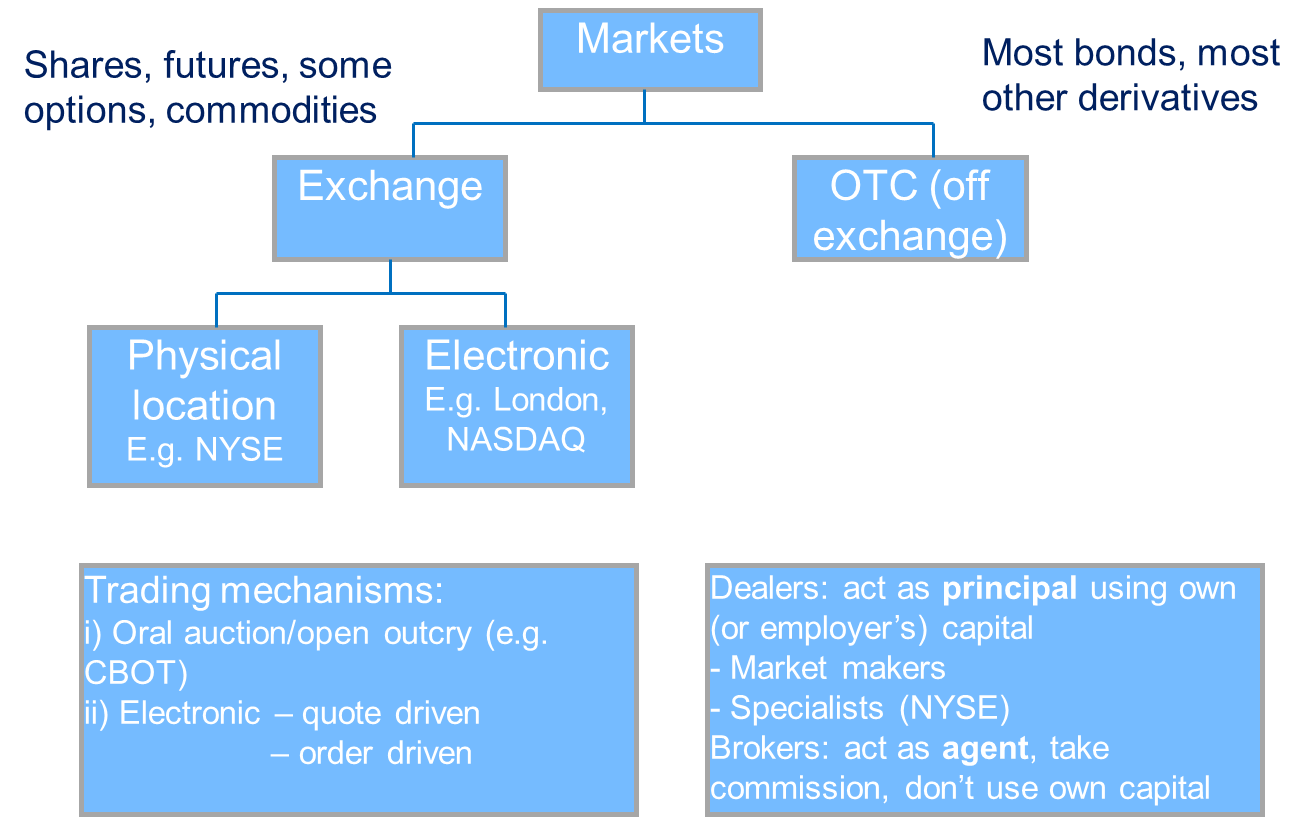

Figure 1 shows a typology of financial markets, with the main types of assets traded

Figure 1 A typology of markets

One type of market: exchanges

A particular type of market is an exchange. This is a step beyond the informal combining of buyers and sellers in a coffee shop. An exchange is a building and organisation specifically designed to bring buyers and sellers together and typically with restrictions on membership. Many old market towns in England have a corn exchange, a building that was originally for the meeting of buyers and sellers of what in the UK is known as corn (cereal crops such as wheat and barley, not corn in the US sense, which in the UK is called maize). The need for such meetings having long since gone, most of these corn exchanges are now shopping or entertainment centres, as they are often the largest structures in the town.

The London Stock Exchange grew out of informal meetings at Jonathan’s Coffee-house in London’s Change Alley in 1698 when John Carstaing began to publish lists of stock and commodity prices. Professional traders in stocks and commodities emerged, becoming known as stockbrokers. As the business became larger and more organised they moved into a building called The Royal Exchange, which was built in 1571 to facilitate commercial trade of all types. But stockbrokers were regarded as too rowdy and badly behaved and were expelled from the Royal Exchange, so they returned to Jonathan’s. Only in 1773 did some 150 brokers and “jobbers” (an English term for what we would now call market makers) set up their own building in Sweeting’s Alley, first called “New Jonathan’s” and then the London Stock Exchange. The business became formalised with membership subscription required from 1801 and the first codified rule book was published in 1812. Note that Philadelphia and New York opened exchanges earlier than London. The Royal Exchange, which sits next to the Bank of England, is now an upmarket shopping mall. (Source: London Stock Exchange: our history)

An exchange has membership, rules and exclusions. It’s more formalised than an open arena in which anybody can turn up and buy and sell. Why formalise a market into an exchange? The key reasons are:

- Reduce credit risk: membership ensures that only people of the right “type” (i.e. supposedly creditworthy and trustworthy) can trade; this reduces the risk of fraud and failure to pay debts (counterparty risk); clearly the risk is not zero and plenty of exchange members in history have turned out to be crooks; and keeping to the right type of people can be a form of social exclusion or prejudice, since only wealthy people or those who speak the “right” way are likely to be admitted.

- Efficient trading: an exchange can standardise procedures and orders in ways that speed up the execution of business and reduce the risk of errors; standardised orders in particular (market, limit etc.) allow brokers to execute even complex client trades with a reduced risk of misunderstanding.

- Specialisation: although distinct roles such as broker and jobber (later dealer) evolved before exchanges, an organised system allows clear professional competences to evolve and improve; clearly this also acts as a barrier to entry by newcomers and raises the commercial value of those professionals.

The exchange itself is a business, so who owns it? An exchange in the early days was often mutually owned by its members, who elected the managers. This ensured that the exchange was responsive to its members needs and reduced the risk of managers having interests at odds with the users.

But in the late twentieth century many exchanges demutualised and became standard for-profit companies. That in turn kicked off a wave of mergers and acquisitions that would have been very difficult with mutual ownership.

Over-the-counter (OTC) markets

Not all financial markets are organised as exchanges. Those that are not are called over-the-counter (OTC) markets, or sometimes just off-exchange. This slightly curious name refers to trading that takes place between a buyer and a seller without any formal intermediary. In practice a lot of those trades are done between clients and banks, which act as market makers (they literally provide the market service). These markets are highly sophisticated and the lack of an exchange in no way implies they are disorganised or inefficient.

OTC markets dominate in risk management products such as derivatives, and some basic securities such as bonds and equities are traded OTC. But broadly speaking larger stocks and government bonds are traded on exchanges.

The last distinction we need to make about financial markets is between physical and electronic. The original financial markets were physical by necessity but it also helped to be able to look into the eyes of a trader and see if he (or, more rarely she) appeared trustworthy, fearful or overconfident. This might prove valuable information to a skilled market operator. A number of financial exchanges still have a physical trading floor, on which traders communicate using open outcry, a combination of verbal and hand signals. The main ones are the New York Stock Exchange and a small number of futures and commodity exchanges such as the Chicago Board of Trade, Chicago Mercantile Exchange and London Metal Exchange. All of these have electronic markets also.

Most stockmarkets are now electronic, as are most other financial markets. Orders are fed into a computer system, if they are relatively small, or are phoned to a broker if they are relatively large or complex. The London stockmarket is now a network of brokers, market makers and clients who can be located anywhere in the world. The “London” aspect of the market is defined only by the fact that the traders must still be members of the LSE.

Types of orders in markets

There are two types of electronic market: quote-driven and order-driven. The simpler mechanism is order-driven, where clients put their orders into a computer system. If a buyer’s and seller’s orders are compatible then they are matched and the transaction takes place, without any human intervention. This works very efficiently for fairly small orders but it requires that for anyone to buy there must be at that time a willing seller. This is not necessarily the case for larger orders.

Quote-driven markets can also be described as dealer-driven, where the word dealer means a market-maker, a person willing to buy or sell using their own capital (or that of their employer). A dealer can and usually will buy even if there is currently no other buyer. So a seller can always sell to a dealer, who thereby makes continuous trading possible during market hours. A dealer provides liquidity, which is a very useful service. To make a profit, the dealer must, on average, buy at a lower price than she or he sells at. This gap is known as the spread between the bid (the price the dealer is willing to buy at) and the offer (the price the dealer is willing to sell at). The cost of being a dealer includes having an inventory of financial assets being traded, which requires funding; and the risk of losses when that inventory falls in value owing to changes in prices. A skilled dealer has to balance the cost of the inventory against the ability to provide liquidity to clients, all the while being alert to the risk that buyers and sellers know more than the dealer, which means they’re trading at an advantage.

Most large exchanges such as the London Stock Exchange have both types of system. Smaller orders are sent to the order-matching system and larger orders go through a market maker.

The full set of roles in financial markets

We can summarise the various types of economic actors and roles that make up a financial market:

- The customer or client, who may be retail or wholesale

- A broker or agent who provides the client with access to the market

- A market maker/dealer who provides the actual liquidity, acting as counterparty to each client’s orders

- A provider of research or financial advice (this is not essential – clients can choose to make their own decisions without advice)

- A regulator

- Transactions services: arrangements for funds transfer, settlement of trades, custody of securities and information services.

A regulator need not be a state-backed person or institution. A mutually owned exchange will normally have a set of rules intended to provide an orderly market and to reassure customers, agents and market makers that disputes will be minimised and dealt with effectively. But in practice, in all developed financial systems the regulatory role is at least partly enshrined in law and breaches of securities regulation are criminal offences.

The provision of the various transactions services is a critical “middle office” and “back office” aspects of markets which is largely about good information technology. Stock exchanges make a large fraction of their profits from these services.

Innovation in markets

There has been a lot of innovation in financial markets in the last twenty years, mainly owing to vastly cheaper technology. Exchanges used to enjoy a de facto (and in some cases legal) monopoly on trading. But now there is a lot of competition from networks set up by investment banks and sometimes by the clients themselves. By lowering the cost of creating new markets, these systems off lower costs and higher confidentiality and have led to a large fraction of stock trading to move off exchanges. One example is dark pools, which are order matching systems that are used mainly by larger clients who benefit from a new source of liquidity (matching larger orders can improve the prices for both buyer and seller) and from the lower level of information disclosure that such systems usually require.

A risk in this innovation is that trading gets fragmented, undermining the central value of a market which is that it brings together as much demand and supply as possible. Securities regulators face something of a dilemma with these new market mechanisms. They don’t want to block innovation that can help a least some clients but they don’t want this benefit to come at the expense of smaller clients who may be worse off as a result of the fragmentation. It’s not at all clear how this will play out.

Leave a Reply