The turbulent financial markets in early 2016 can be seen as a battle between two groups of ideas – the economists see little reason for sudden concern but the markets are worried about hidden risks

*

Global stock markets performed worse in the first few weeks of 2016 than in living memory. Since markets are supposed to be forward looking, this suggests they foresee trouble ahead. The value of a market should reflect the same two things as the value of any financial asset: the estimated flow of future cashflows and the rate at which these flows are discounted. So either the outlook has deteriorated or investors are collectively discounting the same future at a higher rate, meaning they’re more nervous (high risk aversion if you prefer).

But there is little news to suggest a sudden worsening of economic or corporate prospects in the new year. So economists such as Olivier Blanchard, former head of economics at the IMF and now free to speak his mind, argue that the markets are at risk of creating the very risks they fear, because market turbulence that leads to corporate anxiety can cause lower investment, and so a weaker economy.

The other view is that markets have a sort of collective wisdom that identifies things that no individual investor (or at least few) can spot. So markets often fall before worsening economic data, which are almost always a lagging indicator of a slowdown.

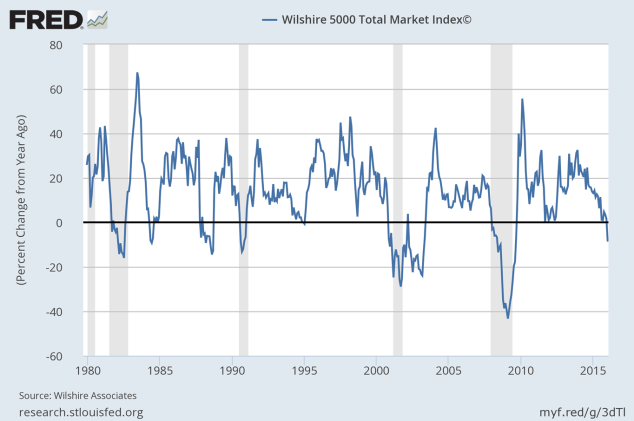

The trouble is that markets often fall for other reasons and provide an unreliable guide to future recessions. As the late Paul Samuelson famously said, the market has predicted nine of the last five recessions. The chart below shows for the US stock market how often there were falls in the market compared with actual economic recessions (shown as the grey bars). Sometimes the market does indeed forecast a recession but sometimes it falls for other reasons.

Specifically there has been no news recently that suggests that China is slowing down any more than we knew in December or November. The latest GDP figures (for what they’re worth) were in line with or even slightly better than expectations. Capital outflows from China, which are causing worries of a future depreciation of the RMB, have probably slowed too.

We know from a recent report from the International Institute of Finance that some of these outflows have been to re-finance Chinese corporate borrowing in dollars into domestic Yuan debt. I first heard this argument in December at a visit to a macro hedge fund in Shanghai. It’s encouraging to hear official support. The quantity is unclear but this is a relatively benign type of outflow. Companies in many developing economies but particularly China have probably borrowed too much in dollars. It made sense when the dollar interest rate was low (which of course it still is, but is possibly going to rise) and when the RMB appeared to stable or rising against the dollar (making future repayments cheaper in domestic currency terms).

Now that both these assumptions are in question, some Chinese companies are repaying their debt early. That is a prudent decision that reduces the risk of financial distress later.

The more worrying type of capital flows are those from Chinese residents seeking a safe home for their savings because they’ve lost confidence in the economy or government or both. There is clearly something of this going on. I was struck by how many people in Shanghai also told me they were worried about the decline of the RMB against the dollar and were looking to move savings abroad.

Some of these concerns arise from a change in the long-standing belief that the RMB would rise relative to the dollar. I believe that remains a correct long term view but short term exchange rates are notoriously hard to predict, and politics can certainly get in the way. It’s clear that many people, both in China and abroad, have lost some confidence in the Chinese government’s ability to manage the economy. Although the official data show that the economy is still growing at about 6.5%, in line with the target, the evidence of longer term rebalancing from heavy industry and capital spending to personal income and consumption is less encouraging. Gavyn Davies showed in his Financial Times blog that the recent shift from industry to services is only true in nominal terms, because of the sharp fall in the prices charged by industrial companies. In real terms there is very little movement. (Gavyn kindly gave us this argument at the MFin City Speaker Series the week before the blog was published).

The IMF’s latest economic outlook was a little less optimistic than in October, but scarcely different enough to justify recent market turbulence.

What is clear is that it’s increasingly silly referring to “emerging markets” as a group. The sharp fall in oil prices is disastrous for Brazil and Russia but very good for China and India. So much for BRICS solidarity.

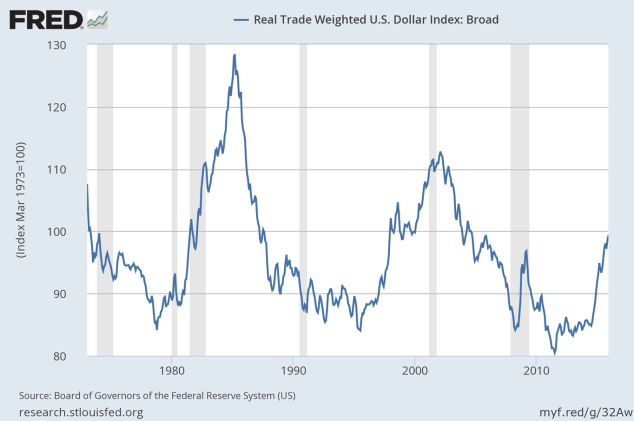

A more serious reason to worry about deteriorating economic growth is in the US. Recent estimates of economic activity there are indicating some risk of a slowdown, probably caused by the strong dollar (see chart below). These “nowcasts” attempt to estimate where the economy is using a wide range of data, before the official data on economic activity are published. Gavyn Davies reports the nowcasts for his investment firm Fulcrum as suggesting some US weakness. The Atlanta branch of the Federal Reserve publishes “GDPNow“, a similar estimate, which suggests a slowdown in the last quarter. The US dollar has strengthened by nearly a quarter against its trading partners, from its trough in 2011, though that only brings it back into line with its average of the last forty years.

So we shall see, as 2016 rolls on, whether there is something nasty lurking out there that the markets have spotted, or whether they are in one of their occasional self-reinforcing storms. Let’s hope it’s the latter.

Lauri Suoranta

DCF is more valid a valuation tool for the market as whole than it is for individual common stock issues (especially when such carry a substantial possibility of M&A activity). Even for the stock market as a whole, liquidity preference of the participants varies faster than expectations about real economy, so I would dispute the idea that markets are trying to predict recessions through collective wisdom. Even the classical portfolio theory tells that increased volatility should result in lowering asset values (increased expected returns). Furthermore, the intense speculation around central banks’ monetary policy means that good news about real economy can actually have negative impact on the stock market (as expectations about easing are diminished).

KXU

Think Paul Samuelson’s quote captures the essence of recent turmoil, at least in a China setting. Needless to say, China equities are over-valued (why wouldn’t it be given it’s been the only major channel of wealth creation for the world’s most populous nation). But the pace of correction taking place is excessive, more akin to that of a recession involving major corporate defaults.

Looking across a few fronts, it’s not doomsday yet. The country has a strictly regulated FX regime, preventing mass capital movements. CBRC regulations have effected the segregation of public equity from bank balance sheets, and NPLs have been gradually coming off banking books, supported by large after-market demand (through AMCs). Even the insurance sector has been well guarded with pre-defined equity investment caps from the financial regulator. These are the most capital intensive sectors of China, without their failure, money will continue to move and sustain the survival of the economy.

But then there is always the question of whether NPL numbers are up-to-date, or is there an unreported wave of companies on the verge of bankruptcy that could lead to massive job losses and social unrest. But that question has hung around for the past decade, just in different forms (first steel sector, then local government platforms, then Wenzhou lending crisis, then more SME and trust related concerns). And yet, people’s livelihood remain intact, no systemic failures have occurred.

It’s a dangerous thing to confuse the speed of hot money with the actual pace of economic development/deterioration. Hopefully the market will soon see that this is one of the four wrongly predicted recessions.