China’s $3.9 trillion foreign exchange reserves were not planned but arose as a side effect of a strategy, now ended, of keeping the RMB exchange rate lower than the market would have set it.

*

Last week I visited the home of China’s SAFE – the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. SAFE’s reserve management division is on Financial Street, a few minutes walk from its parent, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank. We have had two SAFE employees graduate from the MFin and another is currently doing the course. My visit was to nurture therelationship between Cambridge and SAFE and to learn a bit more about this mysterious organisation.

The PBOC releases the foreign exchange reserves total every quarter. At the end of September 2014 they were $3.89 trillion ($3,890,000,000,000) down from $3.97 trillion at the end of June. The fall is explained by exchange rate valuation effects, since not all of the reserves are held in dollars but the dollar rose in that period, reducing the dollar value of those non-dollar assets. After a decade of rapid growth the reserves are now broadly stable. This is evidence that the mechanism which created the reserves, China’s intervention in the foreign exchange market, appears to have stopped.

How do you build reserves?

Foreign reserves for any country represent claims on the rest of the world. Just as for an individual or a company, a country can only generate reserves by saving more than it invests. Reserves represent a net surplus of total foreign exchange inflows over foreign exchange outflows. The total of these flows includes both the current account and the capital account of the balance of payments. For countries that don’t intervene in their currencies, the sum of the two accounts must sum to zero. The demand for foreign currency by residents must be matched by the supply of foreign currency from non-residents (foreigners). If the two are not the same, then the price will adjust – the exchange rate.

The US, like most OECD economies, allows the exchange rate against other currencies to float freely in the market. That means that any imbalance between demand and supply of foreign exchange is eliminated by a change in the exchange rate, the price of dollars in terms of other currencies. This is like any other financial market and many non-financial markets too. At the end of each hour, day and year, the US net demand for foreign exchange has been balanced by a rise or fall in the dollar. The US does hold a small level of reserves (it holds much larger amounts of gold) but those levels remain constant, other than valuation changes, because the US doesn’t try to put a gap between demand and supply of foreign exchange.

One way to think about this is, how is the current account balance of payments financed? Unless it’s exactly zero, the current account deficit or surplus must give rise to a counterpart capital account flow. That flow can arise from private sector transactions or from government (“official sector”) transactions:

Current account = net official flows + net private flows

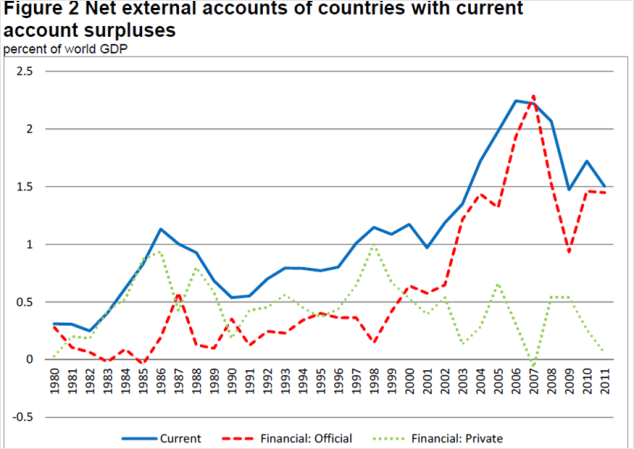

If there are no official flows, as in the case of the US, then the current account is exactly offset by private flows, with any imbalance automatically adjusted through changes in the exchange rate. If however the government (or central bank) intervenes, it can steer the exchange rate away from what it would otherwise have been. This has been quite normal behaviour for a number of countries in the world. The chart below (from a recent report from the Peterson Institute for International Economics) shows that for those countries running current account surpluses in recent years (chiefly in Asia), there was substantial official sector intervention. Note that the private flows were far less than the current account surpluses. In other words, in the absence of official intervention, these countries would have seen the value of their currencies rise. By intervening and building reserves, these nations held down their exchange rates, meaning that other countries’ exchange rates, particularly that of the US, were overvalued relative to what the market would have set.

China has intervened for much of the last twenty years to bring about a lower external value of the RMB than would otherwise have happened. Imagine a Chinese exporter of furniture, which has sent some goods to the US and received dollars in payment. The exporter, which wants RMB, could sell the dollars in the foreign exchange market and buy RMB, which would push up the value of RMB relative to dollars. The PBOC prohibits this, requiring instead that the exporter sells its dollars to the central bank. The dollars thereby acquired are then added to SAFE’s reserves, in effect kept out of the market. That way the RMB trades at a lower price than it would have had, relative to the dollar, in a free market. The newly created RMB, paid to the exporter, could give rise to inflation so the PBOC requires the commercial banks to hold large reserves at the PBOC to offset the otherwise excessive liquidity.

Why did China do this? To make Chinese exporting companies competitive, boosting their employment and output. China’s economic development used to based on export-led growth, taking advantage of China’s formerly low labour costs and a large global market for competitively priced goods. That model was gradually dropped as a policy, in favour of a greater dependence on domestic demand, first from investment and in future from consumption. China’s cost competitiveness has been reduced by fast growth of wages, especially in southern China. The country’s future growth will depend on services and higher value added manufacturing. So it is not longer necessary to keep the RMB down, though the PBOC still intervenes occasionally and can do so in future if it sees fit.

How much is enough?

China is not the only country to build foreign exchange reserves. There was a rapid increase in global reserves from 2000, mainly because many Asian countries, reeling from the financial crisis of 1997-98 which was caused by a sudden withdrawal of foreign lending, wanted to insure themselves against any future turbulence. Seeing Indonesia face a roughly 35% loss of GDP, the forced resignation of the President and a humiliating bail-out from the IMF, concentrated minds. International financial flows are highly unstable and volatile. But cutting your economy off completely from international finance is too costly a solution. So the next best way of protecting your country is to hold a high level of reserves.

Just as for a prudent household, reserves offer a cushion in the event that a country’s credit is suddenly withdrawn. Reserves allow the government to stabilise (to some extent) the exchange rate and to keep buying necessary imports while buying time for a smoother adjustment than the crises that hit Indonesia and several other Asian economies in 1997.

So these economies, and many others around the world that learned the same lesson, started building reserves at an unprecedented rate. To build reserves you need to run balance of payments surpluses, which necessarily means other countries, chiefly the US, have to run deficits. So an important cause of the US shifting into a large foreign deficit in the decade ahead of th global financial crisis was the deliberate policy of national savings run by emerging economies.

China didn’t suffer much in the Asian financial crisis (other than the bankruptcy in 1999 of GITIC – the Guangdong International Trust and Investment Corporation, which defaulted on over $4 billion of debts, mainly to foreigners who believed the government would guarantee the loans). That was because China was financially largely cut off from the rest of the world. Yet China too started building its foreign reserves.

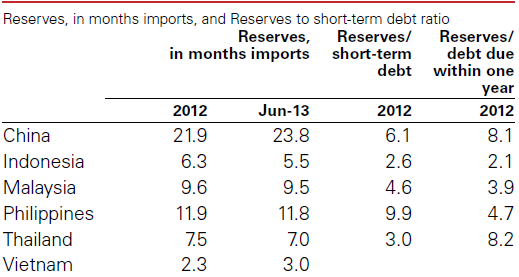

But the level of China’s reserves rose far higher than those of other Asian economies, even allowing for the much larger size of the economy. There are two ways to benchmark reserves. Recall that reserves are a form of insurance or protection. There are two risks that they help to manage. One is a loss of income from exports, which would threaten the country’s ability to pay for its imports. The other is the risk of not being able to repay your (foreign) debt.

So economists typically benchmark reserves against the level of imports, regarding three months as a reasonable level. And they measure them against the level of short term foreign debt, the debt which falls due in a year. Reserves sufficient to pay back all of a country’s short term debt can be considered pretty ample.

On both of these measures China’s reserves are far in excess of “normal” reserve levels (see chart below). That, together with China’s export led growth strategy, provides the basis for saying that China didn’t set out to build its vast reserves as a deliberate policy. The level grew somewhat accidentally, as China kept its exchange rate artifically low.

What can you do with $4 trillion?

The reserves represent a stock of wealth for the Chinese economy, a claim on other countries. China could spend them by buying additional imports from the rest of the world and enjoying a temporary boost to its income. The reserves represent deferred consumption, just as savings in the bank for a household represent future spending power, whenever it is safe to do so. Let’s say that $1 trillion represents a reasonable level of long term reserves. The other $3 trillion could be spent by giving every single Chinese citizen a cheque, in foreign currency, for about $2,300. The surge in consumption that would follow would not be inflationary because it wouldn’t increase demand for domestic resources. There might however be secondary effects from the sudden liquidation of $3 trillion and its most unlikely that the Chinese government would do this.

The reserves may provide some psychological comfort for Beijing policy makers and they do provide a useful resource for whenever China abolishes foreign exchange controls, perhaps 7-10 years from now. That, by definition, will mean China adopting the policy of the US, UK, Eurozone and (most of the time) Japan, of allowing the foreign exchange market to determine the exchange rate. But the reserves might be helpful in managing what could be a turbulent transition period.

The reserves could also be used for capitalising a new international financial institution, perhaps a very large one. China has already committed to setting up a BRICs bank and an Asia Infrastructure Bank. Both of these are rivals to the World Bank and owe much to frustration at the slow speed of change in increasing the shares and votes of developing economies such as China and India in the multilateral institutions set up at the end of the Second World War. China might decide to give up on the IMF, and launch its own international financial institution, which would require far larger amounts of capital than the two new banks. I doubt that it will go that far because there is much more to be gained by reforming the existing IMF, at least when the US Congress finally votes through the increase in capital and associated shift in voting power towards developing economies that has already been agreed.

Traditionally reserves, which are intended for emergency use in a financial crisis, are held in safe, liquid assets such as government bonds and bills. US data for September 2014 shows that China, mainly through SAFE, owns $1.27 trillion of government debt, fractionally ahead of Japan’s US debt holdings. China also owns about $0.3 trillion of “agency” debt (bonds issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which are de facto guaranteed by the federal government). SAFE discloses very little information about its asset allocation but it is clear from public sources that in recent years it has started to invest in equities and real estate, which are not suitable for reserves. In effect, a part of SAFE’s funds are being managed like a sovereign wealth fund (SWF), which usually has a long term investment horizon, and can take both liquidity and asset risk. Confusingly, China already has a SWF, the China Investment Corporation (CIC), set up in 2007 with funds taken from SAFE. There may be some rivalry between the two organisations, inflamed further by the fact that SAFE is a subsidiary of the central bank while CIC falls under the Ministry of Finance. In most countries there is a rivalry and tension between the finance ministry and central banks and China is doubtless no different.

So the reserves sit there, diligently managed by the staff of SAFE, awaiting a long term use.

Leave a Reply