There is a great need for infrastructure investment in both developed and developing countries. The former need both refurbishment of old assets and additional capacity. The latter need lots of new capacity, mainly arising from rapid urbanisation. There is also a large pool of savings in pension funds, companies and sovereign wealth funds that is looking for a safe, long term return over many decades. These are, in principle, just the features of infrastructure project returns. Yet not much funding is being done, certainly far less than is needed. Why?

The commitment problem

The main reason is that infrastructure investing is an extreme case of the problem of commitment. Investors need to be sure that governments won’t expropriate their investment as soon as it’s completed. Governments might not plan to expropriate the investors when they first encourage them to build new infrastructure. But once it has been built there is a strong political temptation to then renege on earlier promises and worsen the returns that the investors make. This is a problem with all long term investment to some extent but it’s particularly a problem with infrastructure, which combines two features: i) it’s socially and politically important: roads, water and power supply really matter to people and therefore have political significance, in a way that investment in ordinary private businesses doesn’t; and ii) infrastructure is usually very capital intensive and involves a large amount of sunk costs: sunk costs are irrecoverable costs; once an investor has paid for a power line or water pipe the capital is irrecoverable.

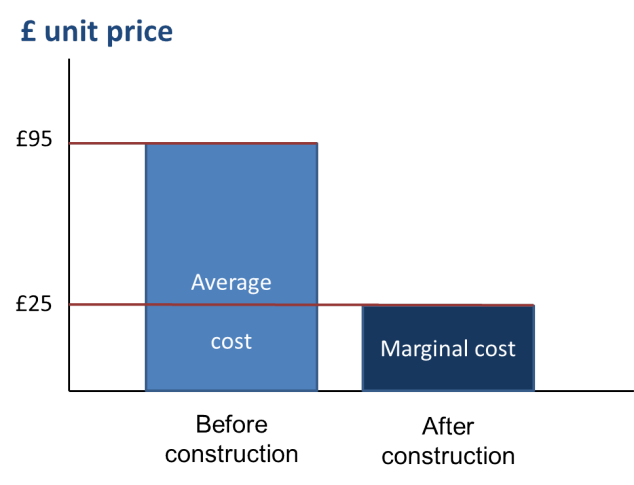

The combination of these gives rise to the classic problem of government commitment. Suppose you are a government which cares about the welfare of your citizens, perhaps because that will influence whether you remain in power. You want new investment in say power generation because that will make your urban population better off. You therefore genuinely want private investment to take place and realise that you must allow the company to charge a price per MWh of electricity that covers both the operating cost and a fair return on capital. In other words, the price must cover the full average cost of production, where that includes a return on capital employed. Let’s assume this is £95/MWh, which is enough to encourage a private investor to proceed with construction. But once the investment has been made you know that the capital is in place and the company cannot reverse it and take the asset elsewhere, or at least it isn’t worth doing so. So you realise that the company will continue to operate the power station so long as they get a price that covers their operating costs i.e. the marginal cost, excluding a return on capital. Let’s say that is £25/MWh. Since the capital is now irrevocably committed, the company will rationally keep operating so long as their cashflows at least cover operations. There is now no need to pay a price high enough to cover the average cost. This chart shows the situation. I haven’t chosen these figures at random. The full price that the British government has guaranteed to the French company EDF for the power generated by the prospective Hinkley Point C nuclear power station is about £95/MWh in 2014 prices. But the marginal cost of operating a nuclear power station is quite low, perhaps around £25/MWh, because the fuel is a very small part of the total cost. Now the investor is not stupid and realises that there is a risk that the government will be incentivised to cut the price in future. So the investor won’t invest at all, unless there is some way for the government to promise credibly not to cut the price once the construction is finished.

The game: how to convince the investor that you won’t renege

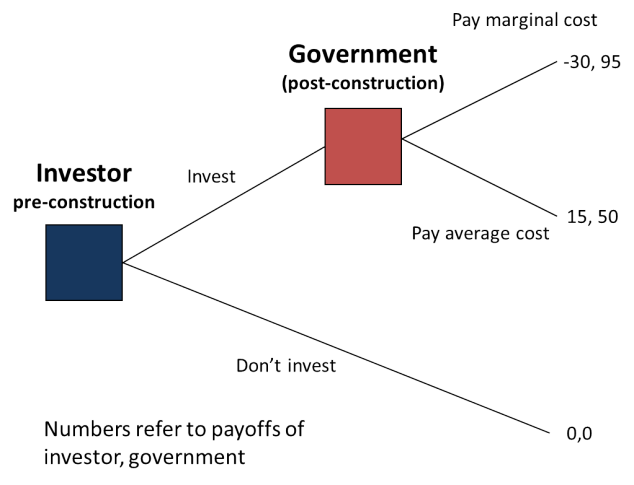

The situation is as shown in the second chart, which shows a simple game. Game theory is the analysis of interdependent decision making, where one agent’s choices depend on what they expect other agents to do in response. In this game, there are two decision makers, who act at different points of time. At the time pre-construction, the investor has to consider whether to go ahead and invest. If there is no investment then there is no benefit to either the investor or to the urban people suffering a lack of power. So the payoff is (0,0) meaning no benefit to either investor or government. If the investor goes ahead and builds the power station, the next decision stage is for the government, after the construction is complete. One option is, pay the agreed average cost, in which case the investor makes a total profit of say 15 but the customers also benefit from not having power shortages, let’s say by an amount of 50. But the government is now strongly incentivised to cut the price paid for the power to only £25, in which case the investor now makes a loss, say -30, because their capital receives no return. That return is transferred instead via a lower price to the customers, who now receive a payoff of 95. If the investor can see the government’s incentive to renege on the contract post-construction, rationally they won’t invest at the start. If the investor expects the payoffs to be as in the game diagram, no power station gets built and the opportunity to reduce power shortages is lost. Everyone is worse off than they could have been.

Note that the government, at the time pre-construction, might genuinely want and intend to pay the full average price of £95 after construction. But the incentive to pay only the £25 marginal cost once the project is complete is terribly tempting, when re-election is pending and a happy urban population would make this more likely. This is an example of what economists call time inconsistency, which crops up quite often in government policy decision making. It’s particularly problematic when there is a long time delay from start to finish of a project, which is often the case with infrastructure investment. It may not even be the same government at the end of the construction as it was at the start.

The difficulty of credible promises

So rational investors won’t invest in any such projects without solid guarantees. The difficulty of providing such guarantees is why so few investors are willing to invest in new infrastructure, even in developed economies. They are relatively happy to invest in existing infrastructure but there is a lack of appetite for “greenfield” infrastructure investment, partly because of construction risk and partly because of the risk of a change in the rules or in allowed returns set by governments or regulators. Governments must somehow convince the investor right at the start that they won’t give in to the temptation in future to cut the price to please the voters. They need to find a way to credibly promise not to do this, but that is hard. Governments are sovereign, so how they can bind themselves to a higher authority? EDF is currently considering its financial investment decision in Hinkley Point C, together with its Chinese investment partners. The station is expected to take up to ten years to build and will then operate for at least 60 years. If it does decide to invest next year, it will be because EDF believes it has a watertight contract with the British government that will protect EDF from every possible political contingency over the next forty five years (assuming ten years for construction and a 35 year power price deal). A contract is legally binding, even with a sovereign government. Britain is one of the few countries in the world where the rule of law is solidly proven and EDF would be able to challenge any breach of the contract in the courts. But EDF’s shareholders will not know for sure whether they’ve made a good decision for many years to come.

Miriam Gordon

I found the article very interesting and offered some new ideas to this debate. However,

do you not think that the fast returns on other possible investments is one of the main discouragements for investing in infrastructure. With the growing markets in financial products (such as the ones that lead to the 2008 crisis), and shareholder value maximization policies adopted by many firms, is the decrease in infrastructure investment not largely due to its lack of competitiveness with other investment opportunities as profits may be smaller and take longer to be delivered?

Simon Taylor

For any investment to attract funding, it must offer a risk/return combination that is competitive. So infrastructure, if it can’t match the returns on other investments, must offer lower risk.