Peer to peer lending (P2PL) is an old idea given a new twist by the Internet: lending from households to businesses without a bank in between. P2P has flourished in the UK in recent years and is now growing fast in China.

Small businesses normally rely on banks for funding because they are too small to access the capital markets (by selling securities). But banks are often reluctant to lend to small businesses, which usually have little collateral (assets for security) and in developing economies often lack any written accounts. The problem is a perennial one that has been made worse in Europe by the shrinkage of lending by banks after their over-expansion up to the financial crisis. So small businesses are desperate for funding. Well established businesses would readily pay 7%-8% for a loan but report that banks are simply uninterested.

Meanwhile ordinary households are offered meagre interest rates on the savings they hold in bank deposit accounts. In the UK you struggle to get more than 1%. That 7-8% would be rather nice, even if there is some risk attached.

If banks can’t or won’t fulfill their economic function of intermediating savers and investors then there is an unmet need on both sides, a potential demand and supply of funds. This gap is now being bridged by P2PL, which is nothing more than a brokerage or matchmaking service for lending.

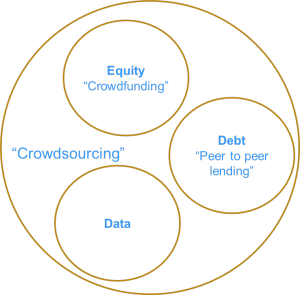

P2PL, like crowdfunding (see below), is a species of the generic idea of crowdsourcing, using the Internet to connect large numbers of relatively small scale participants to achieve a potentially large goal like funding a film or show. This diagram shows the relationships.

Crowdsourcing, a term apparently invented in 2005 by Wired magazine, can involve a flow of money or a flow of information. It has roots in the nineteenth century but it is the Internet that gives it power. Examples are the distribution of large data sets (e.g. from astronomy) to thousands of individual personal computers so people can share computational power. It can mean sharing new products before launch to get customer feedback. Open source software is a form of crowdsourcing, though the usual meaning of the word “crowd” is the general public, rather than experts or specialists. Financial crowdfunding comes in two flavours: debt (P2PL) and equity (crowdfunding).

How do you assess the Credit risk?

There is an obvious problem that has to be overcome for P2PL to be sustainable: how can the lender tell if the borrower is creditworthy? Assessing credit risk is one of the most important functions of banks. It means that depositors can put their money in a bank, reasonably confident that the bank will lend sensibly and make enough profit to pay the depositor without going bust. (History shows that banks donn’t always get this right and sometimes do go bust, with serious consequences for other banks that were sound but who suffered from the general panic. So most countries provide some degree of deposit insurance to reassure the general public and discourage them from all taking their money out of a bank at the first sign of trouble.)

But if you put your money into a P2PL scheme, how do you know if you’re lending to a serious business with good prospects or a dodgy chancer who has little intention of paying you back? P2PL businesses need to show some sort of credit checking process. It’s too costly to do a thorough assessment of every borrower so the checking has to be somewhat formulaic. But that is how banks also do credit checking these days, based on a standard set of questions and ratios.

The only way to tell if the P2PL credit checking process is good enough is experience: how high are the default rates? P2PL started in the UK in 2005 and became mainstream from about 2012. The biggest P2PL sites have hundreds of millions of pounds of loans now. Some US P2PL sites have over a billion dollars on loan. The one I joined, Funding Circle, is for business lending but others such as Zopa (from “zone of possible agreement”) offer personal loans. I joined out of curiosity, to see how the system works. It is very simple to use. The site classifies borrowers according to risk and you can choose the level of risk that you, as a lender, want to take. You deposit some funds and these are then entered into auctions each time a new borrower appears. An important part of the system is that your funds are diversified over many different loans. So instead of all your funds being lent to the first borrower who matches your risk criteria, the funds are instead gradually lent out to ensure you have a good mix of borrowers.

The sites advertise “target” interest rates of 5% or sometimes more, which are an estimate of what you should get, net of fees, and net of defaults. It’s unrealistic to expect no defaults, so the question is what are the realistic default rates? This can only be revealed over time. Occasionally I get an email telling me that a business I have lent to has gone bust. But it’s usually only 2-3% of the total I’ve invested. I haven’t yet got enough data to tell what is a normal default rate. And P2PL is not really old enough to have generated enough data for a reliable estimate. We need data through the whole economic cycle, good and bad. It is characteristic of business loans that they can seem perfectly sound for years then all default at once as the economy turns down. The UK economy has been recovering in the last year or so though it went through a very bad patch before that. Most P2PL only really got going in the last three or four years so unfortunately it’s a bit too early to say how well they do in checking credit.

P2PL is now growing fast in China. For years small businesses found it hard to get bank loans and turned to individuals instead. A lot of unregulated and illegal lending took place, sometimes leading to very severe penalties for those involved. But the web has allowed this sort of lending to migrate online. There was an explosion of P2PL sites in 2012 and 2013 but many closed when the loans they brokered went sour. Much of the lending was channelled into property-related businesses, whether the lenders knew this or not. But P2PL is likely to be a permanant part of the emerging financial landscape in China. Two weeks ago I visited the Beijing office of Baoshang Bank, which is based in Inner Mongolia and has a lot of experience with small rural borrowers. Over lunch one of the team pulled out his phone to show me Baoshang’s own P2PL app, which showed real time lending rates on offer.

P2PL is one of many innovations in finance that depend on the cheap connectivity of the Internet, which radically cuts transaction costs. But does it offer a real benefit? Many financial innovations are at risk of being discredited early on by a single big loss. Regulators, understandably rather skittish after their poor perforance ahead of the global financial crisis, are nervous of the next embarrassing financial scandal. They have generally been tolerant of P2PL but are more cautious on the higher risk equity crowdfunding business.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is the equity sibling to P2PL debt. It offers ordinary people a chance to invest equity in new businesses, a channel which is normally confined to wealthy individuals known as “angel investors”. This is inherently risky, since most new businesses fail. Regulators have been reluctant to allow crowdfunding sites to flourish, even though they might usefully boost the amount of early stage risk capital available to help start ups, for fear that investors underestimate the risk. There are limitations in most countries on the amount of any individual investment, which can be seen as a form of forced diversification.

Enthusiasts for crowdfunding think it could open up a lot more entrepreneurial activity, though it might just finance a wave of over-optimistic flops. Again, only time will tell. There are at least two crowdfunding businesses based in Cambridge, one founded by former Cambridge MBAs and called Syndicate Room. As with P2PL, crowdfunding sites need to solve the evaluation problem: how can investors judge which investments are most likely to pay off? Syndicate Room has members of the Cambridge angels investment club co-invest in companies, which provides two benefits. First, the angels presumably are better than the average investor in judging the quality of the investment. And second, by putting their own money at risk they may be inclined to mentor or help the business, raising the chance that it succeeds.

I’s too early to say whether P2PL or crowdfunding wll flourish. But it is nice to see some innovation in finance that doesn’t involve exotic derivatives and which might just improve the flow of funds to small businesses, which is one of the main purposes of the financial system.

Leave a Reply