Physical money is becoming increasingly unnecessary in everyday life. Could it be heading for extinction and does it matter?

I’ve just spent three days on holiday in the wonderful city of Copenhagen, using physical cash only once (when the ice cream seller’s card machine was broken, and the ice cream is really good so I couldn’t let that stand in our way…). In the UK I use my contactless debit card in almost every shop now. In fact there is very little need to use physical cash – notes and coins – except in pubs, where you will get some rather hostile looks if you try to pay by card. But even there things are changing. The forward looking Weatherspoons now offers contactless card payment, which is quicker and easier than cash. Perhaps even the traditional local will eventually follow.

The benefits of doing without cash are obvious: fewer trips to the ATM, less risk of losing money or having it eaten by pets or being destroyed in your jeans pocket in the washing machine. And for retailers the cost of handling cash, depositing it in a bank (for a fee) and having to give change are all a nuisance.

Furthermore, we know from a recent paper by the leading international macroeconomist and former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff (which I found via Timothy Taylor’s excellent blog), that the majority of cash outstanding is held in very high denomination bills. There is about $4,000 in cash outstanding for every US citizen and 78% of it is in $100 bills or above. Similarly there is roughly €4,000 of euro cash for each Eurozone member state person and a similar proportion held in notes of €50 to €500 (have you ever seen a €500 note?). In Japan 87% of currency outstanding is in the highest denomination, 10,000 yen notes (that’s roughly $100).

It’s difficult to imagine a legal use for high denomination bills on this scale. Why would you pay or accept payment in a stack of notes? The obvious conclusion is that most of these notes are being used for illegal activities, including tax evasion. It’s impossible to say for sure, but around 50% of both dollars and euro currency are probably held abroad. There are of course some countries and territories which use other countries’ currencies without permission (Panama, Kosovo, maybe a future independent Scotland) but not remotely on this scale. Far more likely is that these large denomination notes are used in the “informal” or illegal economies in various parts of the world, with the euro especially used in central and Eastern Europe.

So another benefit of phasing out cash would be that it would strangle or at least raise the costs of illegal activities. Some of the business might move into the legal economy, which means it would incur tax, to the benefit of government finances. Other activities might stop or find alternative currencies. So there is a good case for the major currencies phasing out physical cash simultaneously, to avoid the crooks simply switching from one to another.

A cost: loss of seigniorage

There are two objections, though the second is more a matter of principle.

The first cost of abolishing cash is the loss of seigniorage income to the government. A central bank is a wonderful profit making machine. Its balance sheet (excluding quantitative easing) is quite simple. It issues physical cash, for which there is a demand from banks on behalf of customers. And to buy that cash the banks must pay with something of real value, such as government bonds. So the liability side of a central bank is mainly notes and coins, which are very cheap to produce and require no interest payment. And although technically a liability, those notes and coin are never redeemed, except for new notes and coin.

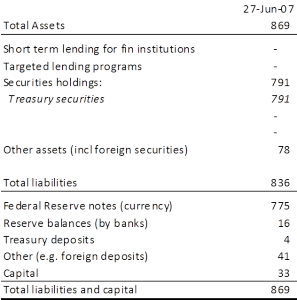

The asset side of the central banks’s balance sheet is mainly government securities, which do pay interest. Here is the Federal Reserve balance sheet in 2007, before quantitative easing led to a huge increase in both liabilities and assets.

To read a balance sheet it’s helpful to think of the liabilities as resources and the assets as the use of those resources.

On the liability side, the Fed holds some funds on behalf of the Federal government (Treasury deposits) and foreign central banks (foreign deposits). And like any bank it has an equity capital base. It also holds reserves owned by the commercial banks, on which the Fed may pay interest. But all of these amount to a small fraction of its liabilities. The great majority of its resources comes from providing physical notes and coins to banks (“currency”), which then issue them to their customers. That is a practically free source of funds to the Fed.

And the Fed uses those free resources to buy Treasury securities, short and long term bonds issued by the Federal government that are risk free and pay interest. It holds some foreign securities for transactions purposes too.

Even at current low interest rates, the Fed could expect to make say 1% on its securities holdings, but pays nothing on its currency liability. So that’s income of $775 bn x 1%, or $7.75 billion a year of risk free income. That is a very effective way to generate a net profit.

This income is called seigniorage, the benefit of being the sole issuer of currency. The word is a throwback to the times when currency was issued by, or in the name of, kings and princes. Today the benefit goes to the central bank but usually profits are shared with the government.

So, abolishing all of that dollar currency outstanding would extinguish most of the Fed’s balance sheet. It would still have reserves from the commercial banks, which are there both for clearing purposes (to settle claims between commercial banks) and as part of monetary policy (to allow the Fed to influence commercial bank interest rates and general volumes of credit). These reserves might increase as cash was phased out, and the Fed could charge interest on them. Indeed this could be a helpful addition to monetary policy options. But the overall scale of the Fed’s operations would be far smaller and it would make less profit.

(Note that the great majority of economic transactions already use electronic money, which is created by commercial banks. Most of what we call the “money supply” is the money in bank deposit accounts, which is a liability of those banks, not the central bank. If we abolished physical cash then the money supply would consist entirely of this privately created money.)

We suggested earlier that there might be some extra taxation from additional economic activity entering the formal sector, though it’s hard to know how big that would be. So the net effect on government finances of abolishing cash could be positive or negative.

Another cost: liberty

There is a second reason why abolishing cash might not be a good idea. That is the principle that people should be free to transact their economic business without the state or anybody else knowing about it. We might argue that nobody really cares about this, unless they have something to hide. But the idea that the state could in principle monitor every economic transaction in the economy is perhaps worrisome. There may be ways to make all transfers ultimately secure and encrypted. And new transaction mechanisms such as Bitcoin may offer anonymity. But Bitcoin’s reputation has been tarnished by the very fact that many of its users have turned out to be criminals seeking anonymity.

The general public seems remarkably relaxed about personal freedom and security so long as they can for their supermarket bill with a card, so perhaps this isn’t a practical concern. If we all use cards more, especially for small transactions, then the only people left using cash will eventually be either crooks or die-hard libertarians. At that point cash could be easily abolished without many complaints. It seems only a matter of time.

Miriam Gordon

If you remember from my comment on your post about Africa’s future development, I am new to economics so I have a few questions about this post too- I would be very grateful if you took the time to answer them.

1. If the Bank of England is unlimited in the amount of money it creates, surely then the amount of money circulating rises consequently increasing inflation as can occur with large reductions in unemployment?

2. To receive money, you said ‘banks must pay with something of real value, such as government bonds’. Does this mean, banks give up bonds they have bought to the Bank of England in exchange for physical money. And then the Bank of England receives the interest on these bonds which are effectively loans which the government promises to repay?

3. Is there not a serious risk, if physical money was removed from the system, that it would become impossible to distinguish between real money and credit. Would it not make it more likely for a credit crunch (as in 2008) to occur as it would be harder to monitor the loans banks were making?

Many Thanks,

Miriam

Simon Taylor

1. The Bank of England can create unlimited amounts of reserve money, meaning reserves owned by the commercial banks with accounts at the Bank of England. This would amount to unlimited quantitative easing. But it has no reason to expand QE beyond what is necessary, and if anything is now likely to reverse its reserve creation, as the British economy is now growing quite fast. But creation of reserves held by the commercial banks has no direct impact on the money in circulation held by the general public. Only if the commercial banks do a lot more lending (which in turn creates new deposits, which means an increase in the money supply) does the money held by the public rise. If that threatens to raise inflation then the Bank of England can (and would) raise interest rates to reduce loan growth.

2. Yes. Commercial banks sell government bonds to the Bank of England in exchange for cash. The Bank receives the interest on those bonds, which is paid by the government. If you think of the Bank as “owned” by the govenment then it’s just an internal transfer within the public sector. Any profit made by the Bank belongs to the government.

3. If physical money disappeared then all money would be bank deposits, which do grow more or less in tandem with bank loans. Each time a bank makes a new loan to a customer it increases that customer’s deposits, in a simultaneous rise in assets and liabilities. So credit growth and money supply growth, which are already closely related, would become even more closely tied. That isn’t so different from now. It would be no more difficult than now for the Bank to monitor the scale and type of bank lending.

Miriam Gordon

Thank you- I follow your points a lot better now.

luiz gonzaga teixeira

the end of the physical money is the most powerful weapon available to stop the trafficking of drugs and weapons, far more powerful than all the combined army and police

JACK

this has to happen A BETTER WORLD

JACK

Money is the cause off most crimes so remove cash from the planet and what a wonderful place it would be LETS DO IT