While the US and UK economies are both recovering quite decisively from their post-crisis recessions, the Eurozone is not. And unemployment is at appalling levels in much of “peripheral” Europe, particularly for young people. Current macroeconomic policy consists of low interest rates from the European Central Bank (ECB) but nothing like the quantitative easing we saw in the US and UK. And fiscal policy remains largely restrictive, reinforced by the German government’s strong belief that countries should aim to balance their national books, against the advice of many macroeconomists who believe that excessive “austerity” has postponed recovery.

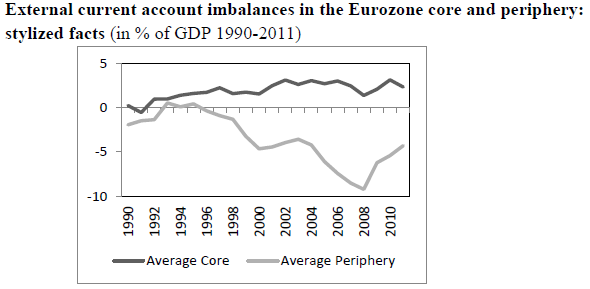

One way of capturing the Eurozone problem is in the balance of payments problems of the peripheral Euro nations (Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Greece and Italy). This chart shows how the periphery went from rough balance to a large deficit in 2008, which is now shrinking because of the contraction in demand of those countries.

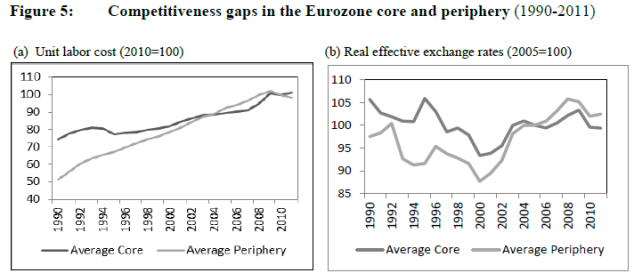

There are two competing but not mutually exclusive views of how the periphery got into trouble. The first, which I’ll call the German narrative, says that these countries allowed their wages to grow far ahead of productivity, making their economies internationally uncompetitive and causing large balance of payments deficits. The excessive growth of demand allowed by governments led to unsustainable booms which have been inevitably followed by busts. Only by correcting – cutting – wages and improving productivity can competitiveness be restored. Governments need therefore to restructure the economy to introduce more competition and raise business efficiency. Unemployment will drive down wages. When wages are competitive again all will be well. The charts below show the much faster growth of unit labour costs (wages relative to productivity) in the periphery relative to the core from 1990 to 2009 and the effect of this in causing a rise in the exchange rate of the periphery versus the core, meaning a loss of competitiveness.

The second explanation argues that the boom in the peripheral nations was caused by the creation of the Euro itself. The removal of currency risk and equalisising of interest rates across the Eurozone led to a big rise in the demand for credit in the countries which most benefitted from getting German levels of interest rates. The supply of credit was met by expanded domestic lending but also by large flows of funds into the peripheral economies from the core, including from German banks. The resulting credit-driven boom was unsustainable and led to rising wages and the loss of competitiveness that the German narrative correctly identifies as a problem. But the cause of the problem lay, in this view, in the Euro itself and the failure to manage overall Eurozone credit growth and flows. Germans lent money to the “irresponsible” peripheral borrowers then complained about it later.

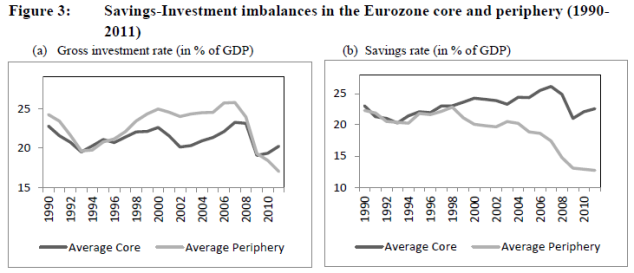

The chart below shows that investment (much of it in real estate) rose in the periphery versus the core while savings fell. For any economy, the gap between national savings and investment is the balance of payments current account surplus or deficit. So this chart tells us that there was some kind of investment boom relative to savings, which necessarily led to current account deficits that were ultimately unsustainable because they entailed rising foreign indebtedness. But the chart doesn’t tell us the cause of that imbalance.

A recent study by two World Bank economists (from which these charts are taken) suggests that the second story is more likely correct and that the investment boom was caused by inflows of funds from the rest of the Eurozone, which financed the unsustainable boom. It’s very difficult to disentange cause and effect in macroeconomics because so many variables are intertwined. There are two possible ways you can investigate a problem like this. The first is to build a detailed macroeconomic model incorporating how we think economies work and then calibrate it against the data. The problem is that macroeconomists disagree about the theoretical framework and the mechanisms that should be put into the model. So the model tends to give you the answers you assumed from the start.

A second approach is to be agnostic about the macro theory and allow the data to speak for themselves. In practice this means using a VAR – Vector Autoregression – approach. VAR (not to be confused with Value at Risk) is a statistical approach in which the researcher tries to use the statistical properties of the data to determine (statistical) causality. Loosely speaking, if including the mean or variance of variable A in a forecast of variable B improves the accuracy of your forecast of variable B then A in some sense causes B. This approach (known as Granger causality) is not foolproof, since there can be complex processes behind the statistical relationship which mean there is no actual causality. But VAR, which was pioneered by Nobel Laureate Christopher Sims, is often a better bet than structural macroeconometric models that have been consistently disappointing since their introduction in the 1950s.

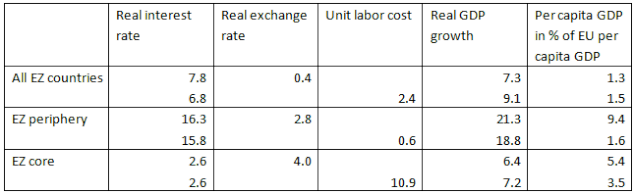

The World Bank authors use the VAR approach and conclude that the factors that caused the balance of payments deficits in the peripheral economies were as shown in the table below. The authors modelled competitiveness first using the real exchange rate and then using unit labour costs. They find that statistically neither of these was very large in causing the balance of payments deficits. It was changes in the real interest rate that were far more important, reflecting the sudden availability of cheap financing available after the creation of the Euro. Fast economic growth was also very important.

What does this mean for policy? One conclusion (not the authors and certainly not the World Bank’s) might be that the Euro is fundamentally flawed in linking together such varied economies in a single financial system. A variation on this might be that the system can work but requires much greater central control and regulation of credit. The Germans are correct in arguing that competitiveness must still be restored but that process is a mutual one – it would be much easier to achieve if German wages and prices rose, rather than relying entirely on them falling in the periphery. This is because we know that wages and prices are “sticky downwards” in most economies, meaning it is very hard to cut them, even when there is very high unemployment. And unemployment is very damaging, both in its human cost and in the long term erosion of human capital that reduces economic growth potential.

But the main conclusion should be that the German narrative is hard to square with the evidence. Germany, the main beneficiary of the creation of the Euro, should acknowledge some responsibility for helping to fix the damage caused to the peripheral economies, which certainly made policy mistakes but were to some extent naive victims of forces beyond their control.

The detailed paper, which the authors emphasise does not represent the views of the World Bank is here. A simplified version is available here.

Leave a Reply