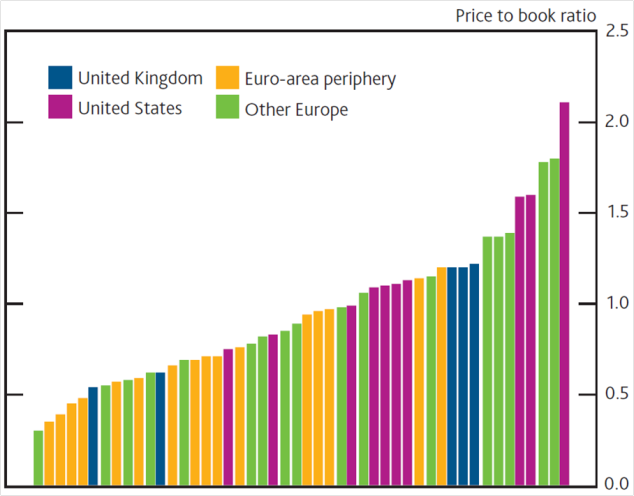

The latest Bank of England Financial Stability Review contains an analysis of Eurozone banks, which still pose a serious risk to the macroeconomy of Europe and therefore the UK. The stock market clearly still has doubts about the prospects of these banks, as shown in the valuation of price to book in the chart below.

Price to book valuation

Price to book is a valuation ratio used only in a few sectors, such as banks. It compares the current share price with the book value of net assets (that shown on the latest balance sheet) per share. The Eurozone banks trade mostly at multiples of less than one. What does this mean?

There are two not mutually exclusive explanations. First, the market may not believe the balance sheet values. The banks publish audited statements so they can’t simply manipulate the numbers. But there is some discretion in whether an asset such as a loan to a real estate company is still worth what it was a year ago. If the loan is still being regularly serviced, at the current low interest rates, then the bank may prefer to record it as still fully performing even if they have grave doubts about the probability that it will be repaid in full. Many property loans in countries like Spain are unlikely to be repaid in full because the underlying asset has fallen so far in value.

If acting conservatively or even just prudently, some of these loans, perhaps a lot, should be written down to reflect a lower than 100% chance of repayment. That would cut the banks’ reported assets but of course it would also cut their reported book value of equity. With so many banks already close to the lower limit of their regulatory equity (“capital”) ratios this is not therefore an appealing course of action. So the markets naturally and reasonably worry that many banks are overstating their true book value, or are at least leaning towards the optimistic side.

The market may get some better information and perhaps reassurance about bank asset quality from the European Central Bank’s Asset Quality Review, which began in November 2013, ahead of the ECB’s assumption of regulatory powers over the larger Eurozone banks. If seen to be credible, the review has the potential to provide valuable information to markets, in the way that the Federal Reserve’s 2009 Supervisory Capital Assessment Programme (better known as stress testing) helped overcome the widespread anxiety about US bank asset quality. Unfortunately the ECB review will take a year to complete.

Pessimism about future returns?

The second possible reason for a low price to book ratio is scepticism about future returns on the banks’ equity. Assuming the book value of the equity is correctly reported then in an efficient market the price to book would reflect the economic opportunities of the banks to make returns, adjusted for each bank’s skill or management quality. An average bank in a competitive industry would make just the cost of equity, meaning a return just enough to satisfy the risk-adjusted return requirements of diversified shareholders. The price to book would then be about one.

A return expected to beat that minimum cost of equity, if likely to persist over time, would lead the value of the shares to rise above book value until the return on the shares was pushed down to the cost of equity. So better run banks or those with exceptional profit opportunities would see their shares rise above book value. In the glory days ahead of the financial crisis some banks saw price to book ratios of two or more, reflecting a (misplaced) optimism from investors who implicitly thought that those banks would make returns double their cost of capital into the indefinite future.

Banking is typically an oligopolistic rather than highly competitive industry which means that long term returns can be higher than they would in a more competitive structure (at the expense of customers). So it might be expected that long term price to book ratios should exceed one, but not markedly so. The chart shows that US banks are now mostly trading at multiples above one, reflecting the cleaning up of their balance sheets and their return to what looks like sustainable profitability. The recent low price to book ratios for Eurozone banks suggest that shareholders believe they are some way from a normal, healthy state.

David

Many thanks for this. The UK banks price to book seems to be plummeting again for some reason. Most down to 0.4 times. The UK housing market is recovering so I can’t put my finger on a reason for this:

https://ycharts.com/companies/RBS/price_to_book_value