I make the point in classroom discussions of the US fiscal outlook that, simplifying only a little, the problem of US federal spending reduces to the problem of the US health care system. All rich countries face an increase in public spending arising from a combination of a higher proportion older people and a rise in health care costs above GDP growth. And there is a general tendency to cost inflation in services above that of the whole economy, known as Baumol’s disease (after the economist William Baumol who first identified it in the 1960s). Productivity growth is much harder to achieve in services, especially public services like health and education than in manufacturing. But wages in services must keep up with those in the rest of the economy so the real costs of labour in those services tends to rise relative to output. Since governments are typically involved with providing a lot of public services, they face an underlying rise in costs that is not offset by productivity growth. But the US starts from a much higher overall health care cost structure and its dependence on private markets, uniquely among mature economies, is likely to make the problem worse in the US than elsewhere.

Market failure in healthcare

Markets do a good job of allocating resources in many areas of economic life. But healthcare isn’t one of them. A classic 1963 article by Kenneth Arrow (one of the most brilliant of American economists and who later won the Nobel Prize for Economics) explained that healthcare suffers from two problems that cause markets to fail. The first is that the normal economics assumption that the consumer is well informed and able to judge among competing products is not true with health. The customer/patient relies on the expertise of a doctor and is unable to choose rationally among doctors, though the increase in data on physician and hospital outcomes has partly reduced the power of this argument.

The second problem is that major health problems are very expensive, far too expensive for most people to be able to pay out of regular income. As with other infrequent but catastrophic costs, people therefore buy insurance policies, which turn a regular affordable payment into a contingent large receipt in the event of a serious illness or accident.

But insurance markets work badly in the case of healthcare because of asymmetric information – the patient/customer knows more about their health and behaviour than the insurance company. Screening can mitigate the asymmetry but Arrow argued that health insurance is likely to be particularly prone to two systemic problems that can affect insurance. The first is adverse selection, or “pre-contractual opportunism”. The people most likely to sign up for health insurance are those most likely to need it, that is the have above average tendency to illness, because of either inherited or behavioural causes.

The second problem is moral hazard – “post-contractual opportunism”. Once insured, people may take less care of themselves knowing that the insurance company will pick up the bill.

There are well established methods of mitigating these problems of insurance markets such as requiring customers to declare all relevant information on pain of voiding the contract if they are later found to have lied and the idea of a deductible, excess of co-payment so that the patient always bears some of the cost of either visiting a doctor or of any later treatment.

But these solutions, which work well enough in say car, fire and travel insurance, work poorly in private health insurance. The US relies on private health insurance (and mostly private healthcare supply) for the majority of the market. The state fills in some of the gaps by providing insurance for those who would otherwise either not be able to afford coverage or who would be denied it on account of being high risks. These are the old, covered by Medicare, and (some of) the poor, covered by Medicaid. The remaining fraction of the population had no coverage until the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”).

The Federal and State governments have a large role in funding health care but they operate mainly through private health insurance, as will Obamacare. The US therefore relies on the effectiveness of a competitive market in both insurance and healthcare services. All other rich countries use government buying power as a force to keep down costs, through their monopsony power. Monopsony means a single buyer, just as monopoly means a single supplier. In both cases the departure from the ideal of a competitive market with lots of buyers and sellers causes a distortion. But in this case the distortion is used to benefit the general public by keeping costs down below what they would otherwise be.

The interaction between private health insurance and private healthcare provision gives rise to another market failure – the third party payment problem (a form of economic externality). Once you have insurance, your demand for healthcare services becomes virtually infinite when you become ill. If there is a brand new, marginally superior but vastly more expensive procedure, you and your physician will demand that you get it. The cost goes back to the insurance company, which then raises everybody’s premium cost. Having some form or co-payment (as in Japan) can reduce this pressure as can the integration of insurance companies with doctors (this is the idea of Health Maintenance Organisations – they internalise the externality). But the relentless upward march of private health costs suggests none of these is an effective solution (though the CBO does see evidence of slower inflation in future – see below).

The US spends more but doesn’t get good results

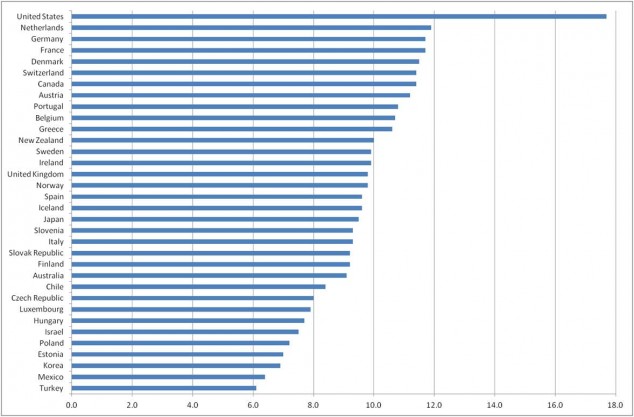

This chart shows OECD data on total spending (public sector and private) on healthcare as a percentage of GDP. The US stands out as spending by far the most of any rich country.

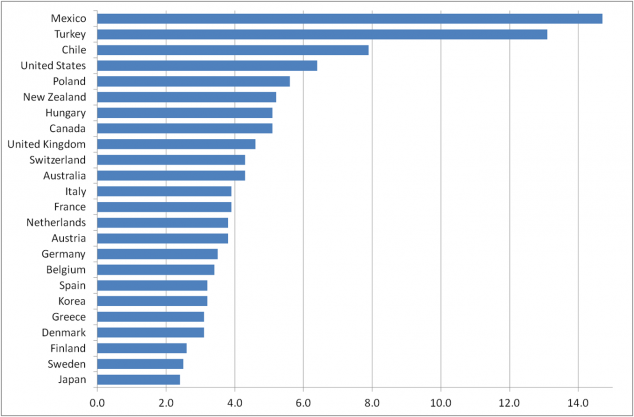

Measuring health outcomes as a means of assessing “value for money” is quite problematic. Health results depend not only on the resources put into healthcare but on diet, lifestyle and the level of inequality in society. On all of these the US does relatively poorly so it might need to spend more on healthcare just to offset them. But most authorities agree that the US still doesn’t get very good results for its high healthcare spending. This chart shows for example infant mortality (deaths per 1,000 live births), where the US has worse figures than any other rich country.

A McKinsey Global Institute report in 2008 estimated that of the total $2.1 trillion spent in the US on healthcare, some $650 billion was “above expected” meaning that it couldn’t be explained by the US level of income and seemed to arise from inefficiencies and institutional problems. That is a serious “tax” on the US economy.

Private costs rise faster than public

So the US system appears to deliver higher costs for poorer results. The high cost of healthcare, including doctors’ salaries and administrative costs, is well know in the US. In the UK doctors are reasonably well paid but few people would choose medicine as a route to a high income, unlike in the US. It might seem that the solution would be to use more private sector discipline and reduce the role of the government, something strongly urged by opponents of Obamacare. But the evidence is that the public sector part of healthcare in the US has been growing more slowly than health care costs.

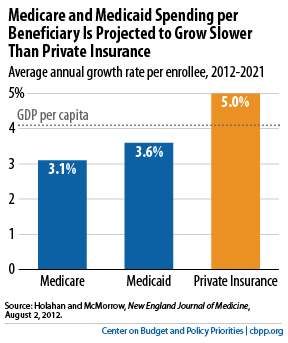

Medicaid spending per beneficiary grew more slowly than private health care costs per beneficiary in the period 2000-2009, according to research done by the Urban Institute for the Kaiser Family Foundation. And it is projected to grow less quickly in the next decade too, according to authors in the New England Journal of Medicine (see graphic below, taken from the Center on Budget and Public Priorities (CBPP).

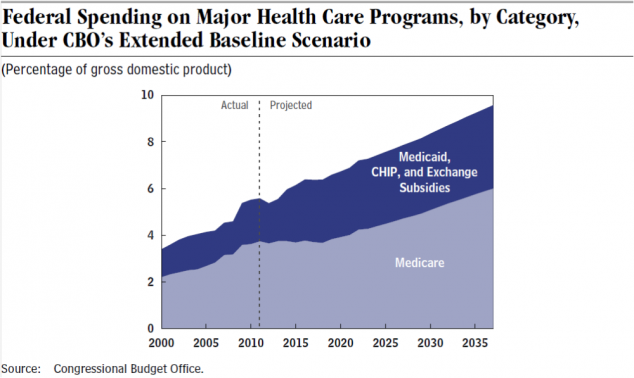

But public healthcare spending, from Medicare and Medicaid, is still projected to grow substantially in future and this is the source of the long term budgetary problem the US faces from health costs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produces annual forecasts of all federal spending. CBO estimates that health spending will suffer from “excess cost growth”, meaning that it will increase more quickly than the underlying growth of economic productivity, adjusted for demographic changes, which are a separate source of rising health costs. They estimate this excess cost growth as 1.6% per year, lower than the historical 2.0% from 1975 to 2010 (CBO The 2012 Long Term Budget Outlook, p.59).

The combination of demography and the excess cost growth is this picture of federal health spending in future.

The CBO comments that “if current laws remained in place, spending on the major federal health care programs alone would grow from more than 5 percent of GDP today to almost 10 percent in 2037 and would continue to increase thereafter. Spending on Social Security is projected to rise but much less sharply.” I’ve added the italics to the second sentence because the point is that it is health care costs that are the problem, far more than social security spending (pensions). Pension costs will also rise for demographic reasons but can be dealt with, in principle, by raising the retirement age and by relatively manageable increases in payroll taxes. (Note that raising the retirement age, in line with increases in longevity, has already been adopted by several other rich countries, including the UK and Germany, but is unfair to those on lower incomes who have tended to enjoy a much shorter increase in life expectancy).

Conclusion: find a way to control health cost inflation

All countries urgently seek ways to halt health cost inflation and instead find ways to improve productivity. It’s possible that IT will provide some efficiencies but the evidence so far is very discouraging. The US provides some of the world’s best health care to those who can afford it. The Japanese healthcare system, which has done a pretty good job so far at dealing with a much more urgent demographic change than in any other rich country, has plenty of problems arising from inadequate funding. Japanese seniors are exceptionally healthy compared with those of other countries but middle aged Japanese are much less healthy owing to a lifestyle and diet closer to that in the west, and costs will therefore rise in future, perhaps converging on those of the US. The US may prefer to keep spending double the share of GDP on health care compared with other rich countries but at some point in the next twenty years the unsustainability of current policies will likely force a change either in the role of the state versus markets or in US federal creditworthiness. And the burden on the private sector is a substantial offset to US corporate competitiveness.

Additional references

Research on why Medicaid costs are lower than for privately insured health: http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/27/4/w318.full.html

Analysis of trend in US healthcare costs: http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.co.uk/2014/04/behind-long-term-rise-in-us-health-care.html

Colin Graves

Not being an economist this helped me quickly grasp the problems of US healthcare funding – thanks.