Every country is unique but some are more unique than others. Japan, though quite obviously not located in the geographic western hemisphere, is part of “the west” as a group of rich democracies with advanced economies. Its inclusion is not because it has any historic link to the west, unlike other eastern hemisphere economic success stories like Australia or New Zealand, or even Hong Kong and Singapore. It is the only example of an advanced economy in Asia. Or, to emphasise political science rather than economics, it is the only example so far of true non-western modernity. Other Asian economies are catching up, such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and coastal China. But Japan has been in the western economic league for a century and a democracy (with some interruptions) for longer than more recent Asian converts.

But Japan, despite being the world’s third largest economy, is largely ignored in the western media. It plays a modest role in world affairs, though it is the largest giver of foreign aid. Its international cultural impact is now far less than that of South Korea. And when it is mentioned it is largely as a cautionary tale, a story of what could happen to the US or European economies if they fail to overcome the risk of stagnation.

But Japan looks to become quite interesting in the next year, for two reasons, both linked to the recent general election in which Shinzo Abe of the traditional ruling Liberal Democratic Party was elected Prime Minister.

Regional tensions

The first is that the Japan is being dragged back into international affairs. Longstanding but previously dormant disputes about ownership of land (sometimes just rocks) in the South China and East China Seas came to life in 2012 with the angry protests in Japan and China over each other’s claims to what China calls Diaoyu and Japan calls the Senkaku. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the claims, matters turned quite ugly in August and trade between the two countries has been badly hit.

The wider context is China’s apparent willingness to pursue its territorial claims in a more active, even aggressive fashion. China finds itself at loggerheads with several regional countries, including Vietnam, the Phillippines and Japan. (Japan also has a separate territorial dispute with South Korea over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands). While China has long historic differences with Vietnam (the two countries fought a war in 1979) and the Phillippines is a relatively weak player in this game, the dispute with Japan has led to the scrambling of fighter jets, although so far no actual firing. Japan has a mutually very profitable trade relationship with China but now faces a difficult process of either standing up to the rising economic power or reaching an accommodation with it.

One key theme of Mr Abe’s election campaign was that of a more assertive and even militarily active Japan. This would be a big step for Japan, which has a clause in its (American written) constitution that blocks military action. It would be a potentially worrying step for Japan’s neighbors, many of which suffered at the hands of the Japanese empire ended by World War II. Unresolved tensions over the actions of Japan’s army in the region during the 1930s, barely acknowledged or even denied by politicians such as Mr Abe, make Japanese nationalism a controversial matter.

Japan has relied on its close military alliance with the US but it is reasonable to doubt whether the US has the means or will to defend Japan in the event of hostilities with China, notwithstanding President Obama’s “pivot” to Asia. Japan’s prudent self interest might require an expansion of its military capability. The US remains militarily dominant in the region but the American people and their pockets are tired of distant wars.

Trying to reverse deflation

The second theme of Mr Abe’s election campaign was the economy, and this is where something very interesting seems likely to happen. As my students are tired of hearing from me, Japan has by far the largest government debt burden in the world but has not yet faced a credit crisis because the vast majority of the debt is held by Japanese investors, not foreigners. Forecasts by many commentators of financial disaster in Japan over the last decade have so far been proven wrong. But the commentators must be right eventually. Japan has the unfortunate combination of a near-static economy, an aging population and government debt to GDP of 220%.

Successive Japanese governments have failed to break the downward spiral. The Bank of Japan is widely regarded as lacking boldness in its attempts to fight deflation, though this may be a bit harsh given the unusual problems the country faces. Prime Minister Abe seems likely to try something very bold, which offers a (relatively) safe experiment for the US and Europe to watch and learn from.

According to this article by Tim Duy (whose blog is an essential guide to understanding US monetary policy) the idea is to push the Bank of Japan into financing new government spending by the creation of new money. This is truly “printing money” and would represent a radical, possibly reckless attempt to get Japanese consumers to spend more, to boost the economy, raise taxes and ultimately reduce the debt/GDP ratio.

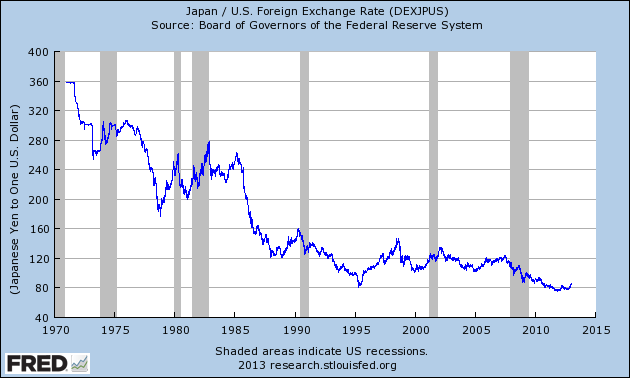

An alternative view is that Abe’s real goal is a lower yen, which would likely follow a rise in inflation and would lead to higher inflation in future. But it would also boost corporate competitiveness, helping to reverse Japan’s declining world export share. Many Japanese see the dramatic rise in the yen in 1985, as part of the G7’s Plaza Accord, the last time that the leading economies successfully manipulated global exchange rates, as the strategic error that led to the gigantic financial bubble of the late 1908s and the subsequent historically unparalleled collapse, the consequences of which continue today.

The graph below shows the dollar/yen exchange rate. Note that a fall in the line represents a rise in the value of the yen. From 1985 to 1988 the yen doubled in value from about 240 to the dollar to 120. This led to very cheap imports into Japan at the same time as massively reducing the export competitiveness of Japanese firms.

An IMF analysis of this question in the World Economic Outlook of 2011 (box 1.4) concluded that the Yen appreciation contributed to the subsequent lost decades of growth but there was nothing inevitable about this, it reflected a mixture of very high leverage in Japanese banks combined with policy mistakes. This matter has taken on added importance in the context of the US contention that China’s RMB is undervalued and needs to be raised. China understandably wants to avoid anything like the Japanese experience.

Pessimists see Abe’s radical approach as risking the independence and credibility of the central bank and putting Japan on the path not to modest inflation of 2-3%, which would be welcome, but much higher inflation that would cause a collapse in confidence in the government and a large rise in interest rates.

Japan as guinea pig

This is interesting because, as Prof Duy says, it means that previously theoretical policy ideas discussed by Ben Bernanke before he became Chairman of the Fed, are likely to be tried out in practice. Bernanke, a scholar of the great depression, spoke in 2003 about how Japan might combat deflation through monetary policy. This was just about on the spectrum of possibilities in the US at that time but not very likely. It has been a continuing reality for Japan for over a decade (and prices were still falling, slightly, in November 2012).

Bernanke’s point was that the combination of government spending, or tax cuts, with an accommodating central bank, was unstoppable. If the government spends enough, for example by sending everyone a large tax rebate, financed by the central bank financing it by creating new money, then this must eventually push any economy into inflation. But it has been an article of faith among mainstream economists that printing money is a bad idea, since inflation may be easy to start and hard to halt.

A policy of tax rebates funded by central bank money creation is equivalent to the “helicopter drop” idea of leading monetarist economist Milton Friedman. Friedman believed that the main reason for the collapse of the US economy in the early 1930s was that the Fed allowed the money supply to contract. He argued that in such a situation expanding the money supply was an essential tool of economic policy. If normal measures didn’t work then dropping money out of helicopters would do the trick, though it would be hard to calibrate it so as to avoid over-shooting into excessive inflation. Ben Bernanke made reference to the idea in another important speech on fighting deflation, in 2002.

Note that the policies of the Fed, Bank of England and European Central Bank in recent years differ from “printing money” in that the central banks bought existing government bonds. They did not buy new bonds issued directly by the government – the ECB isn’t even allowed to do this. The difference may seem trivial but represents the boundary between unorthodox but mainstream central bank action and policy that is seen as leading to ruin, as it has in many countries historically.

I’ve mentioned before that the lessons of German economic history seem to have been mis-learned. Germany lives with the folk memory of the disastrous hyperinflation of 1922-23, which was caused by the massive funding of government deficits by the Reichsbank printing money. But it was the consequences of deflation – mass unemployment – which brought the Nazis to power in 1932, and the threat of deflation should be seen as equally dangerous to democracy.

So if Japan does attempt the direct central bank financing of government spending, it will be a very interesting exercise for us to watch and learn from. One suspects that Japanese voters, having seen the failure of all other policies, are willing to try something bolder, on the basis that disaster is already approaching slowly and the risk of it coming a bit more quickly is worth taking if there is a real chance that this might turn things around. We in the UK, where the threat of long term stagnation is quite real, will watch (from a safe distance) with interest.

rayr

Interesting article. Allow me to suggest a reading of the articles and books on Japanese history and current affairs available free on the following web site to gain a better understanding of the Japanese view of these things:

http://www.sdh-fact.com