Financial markets set the prices of assets such as stocks and bonds through the interaction of demand and supply. Deliberate attempts to fix or distort those prices, termed “market abuse” in the EU, are therefore usually illegal.

But there is an exception. When companies first list their shares on a stock exchange in an Initial Public Offering (IPO), it is legal for the underwriting banks to stabilise the price by using their traders to buy or sell stock in the market, for up to a calendar month (in the US). The benefit of this is that any unusually large trades in the stock are absorbed or damped by the underwriters until the company’s shares reach a “normal” level of ownership and trading. But it is, quite clearly, a form of market manipulation. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) allows this form of market stabilisation under Regulation M.

Using a greenshoe option to manage the post-IPO price

Normally stabilisation is done through a so-called greenshoe option, named after the Green Shoe company for which this was first used, in 1960. Formally it is known as an over-allotment option.

The underwriter(s) of the IPO agree with the client who is selling the shares two things. First, if the offering is for say 10m shares, then the investment banks will actually sell a higher number than this, say 11.5m, meaning that the banks are creating a technical short position. That is, they start with 10m shares and sell 11.5m, and so they need somehow to close the gap, because there are only 10m shares actually available, so they need to deliver an additional 1.5m shares somehow. Part of the reason for doing this is to avoid the risk that investors sign up for the shares in the IPO process and change their mind and withdraw at the last minute.

Second, they agree with the selling client the right (option) to buy up to 1.5m additional shares at the IPO price. So they can close the gap (their short position) at a cost no higher than the IPO price at which they sold the shares.

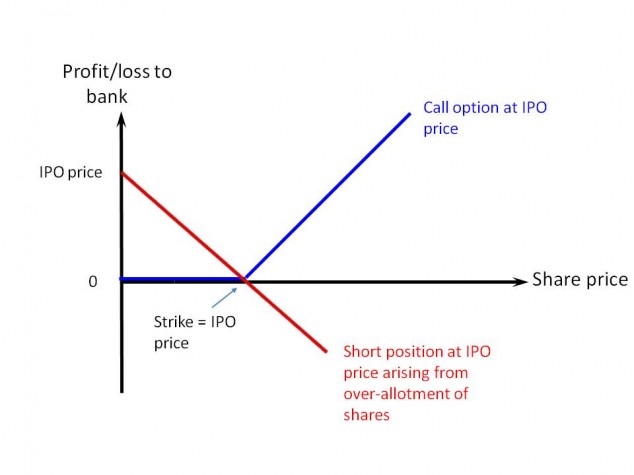

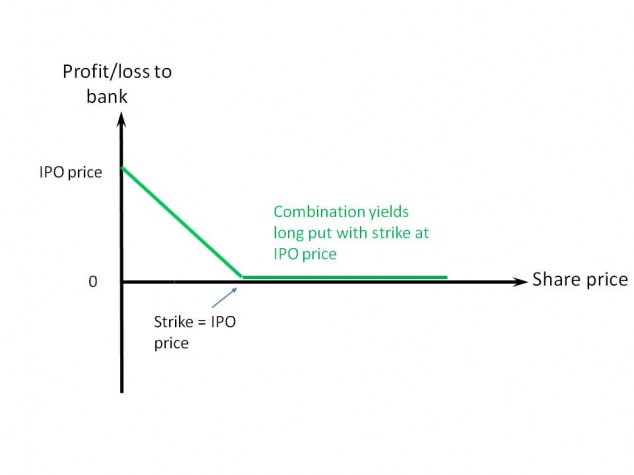

Note that this means the banks have: i) a short position at the IPO price; and ii) a call option on the shares at the IPO price. In combination this means the banks are long a put option at the IPO price. They make no money if the shares trade above the IPO price but they would make money if the shares fall below that price. But a fall in the price below the IPO level is embarrassing and damaging to the banks’ business reputation, so they would probably prefer to try to keep the price above that level, even if it cost them trading profits.

The banks appear to have an interest in the stock price falling below the IPO price but although that would make them a profit on a specific IPO it would be bad for their long term business reputation, which requires that the IPOs they underwrite have rising shares and are seen as successful.

The greenshoe option allows the banks to intervene in the market during the days after the IPO is completed. If the shares trade above the IPO price, which is usually the case and what the banks wish for, then the banks close their position by buying the additional shares from the selling client, with no risk of trading loss because they can buy at the IPO price. The strong demand for the shares is matched by an extra rise in supply and both the selling client and the new investors in the shares are happy, with the bank stabilising the market at low cost or risk to itself.

If the offering is unsuccessful and the shares fall below the IPO price, which might trigger a lot more selling and an unstable disorderly market, the banks close their position by buying in the shares in the market. In doing so they try to push the market price back up to at least the IPO level. It is rare that offerings trade well below their IPO price so it is normally a matter of quietly buying stock in the market until the total 10m shares remain and hopefully by then the share price has stabilised.

The Facebook case

This is relevant to the Facebook IPO fiasco in May 2012, when the shares traded well below their IPO price of $38 – they are currently (November 2012) $21 (NASDAQ:FB). A research report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York looks at the evidence of price stabilisation after the IPO and concludes that the underwriters (chiefly Morgan Stanley) lost around $66m in their attempts to stabilise the price. Regulation M requires the possibility of price stabilisation to be disclosed in an IPO prospectus but the actual market transactions undertaken by the underwriting banks are not disclosed. The FRBNY cannot therefore be certain of what Morgan Stanley was doing but they observe large trades at the exact integer share prices of $38 and $40 which are highly suggestive of price stabilising behaviour.

The analysis suggests that Morgan Stanley tried unsuccessfully to stabilise the price on the first day at $40. After a period of buying at that price, the shares fell, suggesting that it was only the underwriter holding them up. But the apparent stabilisation later on the first day at $38 (the IPO price) was successful in that other orders (presumably from real investors) came in at slightly above $38 and the shares closed on the first day at $38.23, not great but marginally above the IPO price. Part of the underwriting bank’s goal is to establish in the minds of investors that there is some “natural” floor to the price which encourages them to buy with confidence that the share will not fall further. Obviously this was not successful in the succeeding days as the shares fell sharply. On the second day they closed at $34.14 and after nine days were down to $27.72.

The FRBNY authors also note that it appears there was no use of the greenshoe option – the number of shares in the “free float” (that is, not owned by the original shareholders who sold in the IPO) didn’t rise, which it would have done if the banks had exercised their option to buy additional shares at $38. The authors conclude that the banks had a choice between protecting their short term trading profit and loss position and trying to keep the shareprice up and make the IPO a success, which would help their long term reputation and profitability as well as showing loyalty to the selling clients (the pre-IPO shareholders). They conclude that the banks chose to go for long term reputation and profitability, although as it turned out the IPO was seen as one of the most unsuccessful in years so the banks ended up making the worst of both cases.

British Energy’s IPO and privatisation 1996

The British government sold its shares in the nuclear power company British Energy plc in an offering in July 1996 managed by the bank I then worked for, BZW (Barclays’ investment bank subsidiary). It was a controversial transaction because nuclear power had not previously been owned in the private sector in the UK (though it had long been so in the US, Japan, Germany and Belgium among others). Some very last minute press coverage of a relatively small fault at one station led one of the shareholders which had bought in the IPO to dump its shares on the first day of trading. This triggered a wave of selling and the shares closed, uniquely for a British privatisation offering, at below the IPO price on the first day. The selling continued in later days and the underwriter BZW ended up buying back around 12% of the shares on behalf of the government, a dismal failure.

But when that 12% stake was placed back in the market in December 1996, the price had risen and the government (taxpayer) ended up £33m better off than if they had all been sold at the original IPO price. The full story is told in my (absurdly over-priced) book.

Leave a Reply