Yesterday in class a question arose as to whether the Federal Reserve (the US central bank) is keeping US government interest rates down by buying government bonds in the market. By adding to the demand for bonds, relative to a given supply, the Fed would be pushing up the price and this would automatically push down the effective interest rate, because the coupon paid on the bonds (the cash interest paid) is fixed.

An earlier stage of the Fed’s quantitative easing policy (see this earlier blog) definitely tried to do this. But in the last nine months the Fed has bought very few government bonds in the market. Indeed, in the second quarter of 2012 the Fed sold $19bn, though that is trivial compared with the issuance of bonds that quarter of $1,183bn. Most of the bonds were bought by the general public ($844bn), by banks ($138bn) and by foreigners ($449bn). The foreigners include central banks, sovereign wealth funds and private foreign funds. Recently this buying has not been from China, which has seen its balance of payments move from large surplus to a small deficit (see this blog).

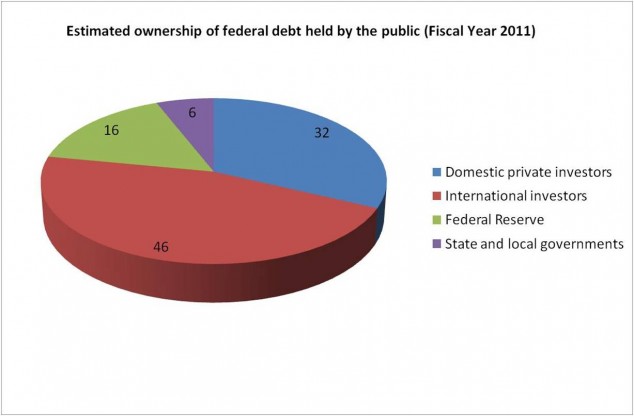

Further discussion raised the matter of the debt that is not held by the public. The total federal US debt outstanding at the end of August 2012 was $16,016bn – $16 trillion. Of that, $11.3 trillion (70%) was “debt held by the public”. This includes the holdings by the Federal Reserve, which were $1.65trn at 26 August (the Fed publishes its balance sheet weekly, the federal debt outstanding comes out monthly).

Intragovernmental debt

But there is another category, “Intragovernmental Holdings.” This was $4.7trn at the end of August, about 30% of the total. What is this?

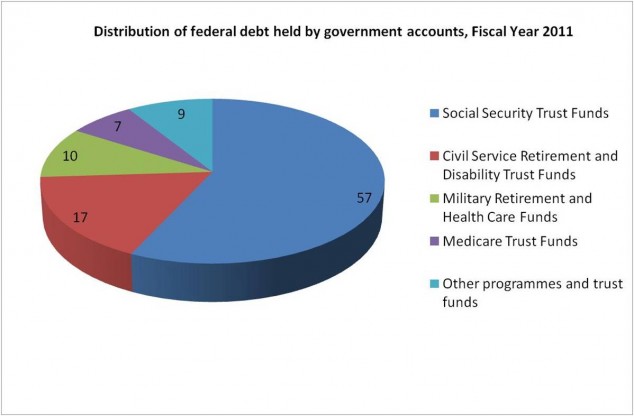

This is federal debt owned by other federal government accounts. (The Fed is not one of these, so its holdings count as holdings by the “public”.) The pie chart below shows that these accounts include: the Social Security Trust Fund (57% of the total amount); Military Retirement and Health Care Funds (10%); Civil Service Retirement and Disability Trust Funds (17%); and Medicare Trust Funds (7%). All of these are entities set up to ring fence (and therefore protect from future government policy changes) obligations to various types of Americans in future. The data, with further explanation, is available at the Government Accountability Office website.

So, what is the status of this debt? Why is routinely left out of the discussion about federal debt, which uses the “debt held by the public” amount? Take Social Security. The Trust Fund takes in tax payments and makes social security (pension) payments. It has had a surplus for many years but in 2010 moved into deficit on its non-interest income. If you add the interest income on its holdings of treasury bonds it is still in surplus but it is only a matter of time before it moves into deficit. All of the surplus income over the years has been invested, as by law it must, in US government bonds.

If the Trust Fund didn’t exist and instead the payroll tax and other taxes had gone into the government’s normal general treasury funds, then the government’s deficit would have been much smaller. So it would have issued fewer government bonds. In that sense, the debt held by the Trust Funds is not “real” debt in the sense of the debt held by the public. Put another way, if you consolidate the Trust Funds into the general government accounts, the assets and liabilities cancel out and there is no net debt. This is widely accepted so the focus of US government indebtedness is on the debt held by the public. The amount of intragovernmental debt is of no significance for interest rates or monetary policy.

If we accept that consolidation story though, we have to accept that if the government had issued less debt in the past, in future the government would have had to issue more debt in order to pay for the future social security payments. So the existence of the Social Security Trust Fund is partly a matter of the timing of debt issuance and of the recognition now of future obligations. That is precisely why it was created, to keep this category of very important government payments separate from others and to make sure that the public and politicians have an annual report on the Funds and their future liabilities. Many other countries have no such mechanism. The pension obligations are simply one among many categories of government spending and it is easy to ignore the future liabilities, which is convenient for short term politicians but potentially disastrous for the longer term future.

The long term US fiscal problem

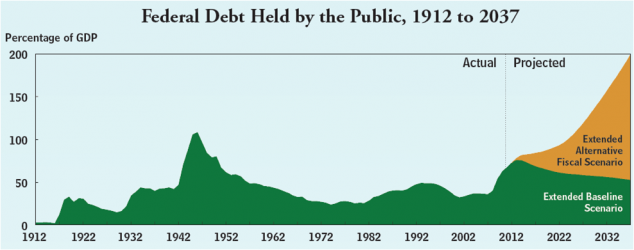

The importance of the Trust Funds is in the overall financial position of the federal government. And that is potentially serious: see the graph below from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The CBO makes two sets of projections. The first, the Extended Baseline scenario, assumes that governments will do all the tough things they say they will do and includes the reversal of the Bush tax cuts that is officially timetabled (implausibly) for early 2013. The second, the Extended Alternative Fiscal scenario, is more realistic and worrying. The CBO notes that under the EAF scenario “The explosive path of federal debt underscores the need for major changes to current policies”.

The US people expect future governments to provide pensions and some portion of health care costs. An ageing population, combined with high health cost inflation makes this a very large future liability. The most important threat to the financial credibility of the US government is spirally healthcare costs. All rich countries face this to some degree but the uniquely expensive and inefficient system of healthcare in the US makes it a more pressing problem there.

The arrangement of federal debt makes no difference to this problem. The costs will fall on the US economy, either through payments by private individuals to health insurers or via the government through tax payments. There is no additional pot of assets to pay for this. The US could set up a sovereign wealth fund and invest all the Trust Fund assets in foreign equities. But this would be politically impossible and would mean a sudden diversion of funds out of the US economy. The existence of the Trust Fund in this sense can be misleading, if it suggests that there is some separate pool of financial resources that can fund the liabilities. Only the timing of tax payments is affected, which means the distribution of the burden between generations.

Nick

As one of the few Yankee’s in my JBS year, I’m always a little worried when the conversation turned to the US in lectures, as many classmates often somewhat incomplete understanding of US policy making.

It’s nice to see someone dig through the nitty gritty of how the non-simple mechanics of US budgets fit together. But I’ve got to object to your comment that the Bush tax cuts are ‘implausibly timetabled’ to expire in 2013.

First, there’s nothing timetabled about it. Without further legislative action they will expire in 2013, full stop. Saying that they’re timetabled to expire implies that it’s just a plan, rather than a legal requirement.

It’s only implausible if you think it’s likely that Congress will act to extend it in the next few months, which under normal circumstances would be pretty likely (no congressman ever lost an election voting for tax cuts). But we haven’t been in normal Congressional circumstances in 2-3 years. One party is committed to intransigence as a core political position, and the other has an incentive to let the cuts lapse to improve their political position.

It’s definitely possible that the cuts will be extended, there’s a distinct chance (especially with a Democratic President) that at least the top marginal rate cuts will be allowed to expire.