Quantitative easing (QE) has become a highly controversial policy, particularly in the USA, where the Federal Reserve has been criticised by politicians, investors and academics up to and including the charge of treason. Yet the Chairman of the Fed, Ben Bernanke, is a highly respected former academic economist, a scholar of the 1930s great depression and shows no previous signs of crazy or anti-American behaviour. And although he can influence his colleagues, he is not a dictator. The last vote, on QE3, was opposed by only one of the Fed’s 12 board members.

Leaving aside the politically-charged hyperbole of failed presidential contender Rick Perry, there are genuine economic concerns about what is more accurately termed unorthodox monetary policy. The Bank of England and European Central Bank’s policies have aroused similar worries in the UK and Eurozone.

Standard or orthodox monetary policy involves raising or lowering the short term interest rate to cool or stimulate the economy. The Fed’s “dual mandate” requires it to try to keep inflation low and to maximise employment. The BoE and ECB are required to target inflation first and only then to try to keep economic growth high. All of these central banks can pretty much control the short term interest rate exactly, by buying or selling short term government securities. In the US the target is the Fed Funds rate, the rate of interest at which commercial banks lend to each other overnight in New York.

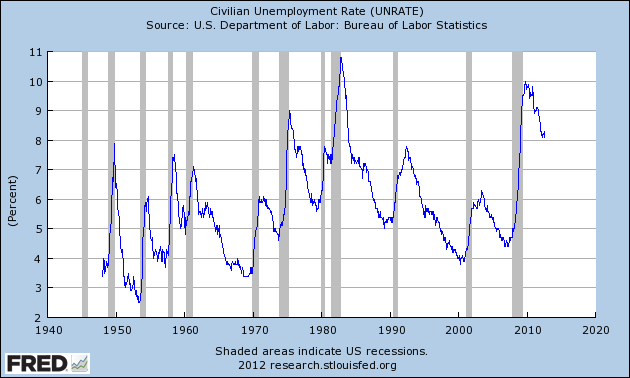

The problem: unemployment is not falling fast enough

The policy had many years of apparent success. Inflation in the US and UK, after reaching double digit levels in the late 1970s, was brought down to low single digits and has remained there for most of the last twenty years. But what is now widely termed the “great recession” arising from the financial crisis of 2007-09 has not responded to orthodox monetary policy. Unemployment in the US is still over 8%, higher than would be expected at this stage of the recovery (see chart below), despite the Fed cutting short term rates to 0.5% since late 2008, the lowest level in the last sixty years.

Worse, there is evidence that the official unemployment rate understates the problem as there has an unusually large fall in the percentage of the population active in the labour force, suggesting many people have given up looking for work but would like a job if they could find one.

So the Fed, having used up all of its ammunition on short term rates, (there are practical problems with cutting to zero, and it’s unlikely it would make any difference), started to use unorthodox policies. These have gone by the name QE but critics tend to prefer the name “printing money”.

Technically this is not accurate but the essence is true. In the days when most money was actual cash, a central bank (or more likely in those days the government or king, emperor, dictator) would literally print more currency. This cost virtually nothing but could be used to settle the government’s debts. At least, it could until people realised that the volume of currency was being increased – it was being debased. If people lost confidence in the currency there would be inflation, meaning that the value of money fell relative to the goods and services it is used to buy. Equivalently, prices in general rise.

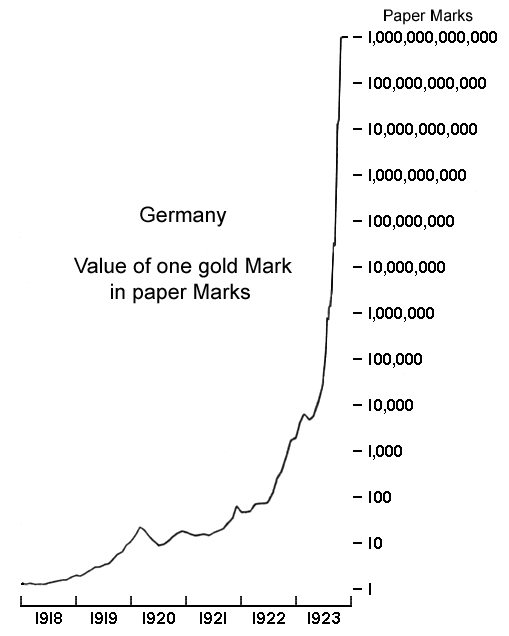

Hyperinflation is truly bad

Several episodes in history offer caution against printing money, most infamously the German Reichsmark hyperinflation of 1921-24. Although not the largest such hyperinflation (Zimbabwe more recently beat the record) it is both the most well known and the most important because of its lasting influence on German attitudes to inflation and monetary policy, which are highly relevant today.

Modern QE works in a similar way to printing money, in that it uses the central bank’s unique monopoly power to create money. Orthodox monetary policy is about controlling the short term interest rate, on which many economic decisions are based. But if it can’t be pushed down any further, the next option is to target the longer term interest rate, the rate on longer term bonds, where long term means perhaps three years maturity and longer. These interest rates are important for capital investment decisions, including buying houses. In the US most mortgages are funded on a long term fixed rate basis. So reducing long term interest rates should stimulate investment and help home buyers, which indirectly should boost consumption spending and accelerate the process of repairing the damaged balance sheet of the US household sector.

Normally the long term interest rate is set by market forces, demand and supply for long term capital. The central bank has only indirect influence on these rates through the link to the short term rate. But by entering the market as a major player it can increase the demand for long term bonds, and by doing so push up their price. Since these bonds have a fixed coupon payment, the market interest rate falls, as you are receiving the same income but on a higher market value of the bond.

QE: buying bonds from banks and paying them with created money

The similarity with printing money is in how this is done. The Fed (or BoE) buys long term bonds from the banks, offering just a slightly higher price that will incentivise the bank to sell (there is no compulsion). It pays the bank for crediting the banks’s account at the Fed. All banks must hold these accounts, partly for reasons of basic transaction “plumbing” but also as a means of influencing the banks. The Fed can increase these bank reserves held at the Fed by the stroke of a computer key – it costs nothing to the Fed to do so and is equivalent, economically, to the old days of printing brand new currency. No new actual currency is likely to arise from this process but the total stock of money in the economy, which includes the banks’ reserves at the Fed, has gone up.

Critics, noting the functional similarity with the dangerous process of printing money, think the Fed is mad, reckless or, as we heard above, somehow out to damage the American republic. But the Fed’s argument is that it is required by its mandate to try additional monetary policy measure to stimulate the economy, which is showing insuficient vigour to bring down unemployment. Here is a sentence from the press release announcing what has been termed QE3: “The Committee is concerned that, without further policy accommodation, economic growth might not be strong enough to generate sustained improvement in labor market conditions.” Policy accommodation means the Fed using its unique power of creating money.

Clearly Ben Bernanke and all but one of his colleagues believe that the policy is right. They don’t pretend the risk of inflation is zero. They are confident that the benefit of QE is higher than the costs. If inflation were to start rising, the Fed would do what is necessary to stop it, including a reversal of the QE measures and a rise in short term interest rates. The Fed and other central banks have learned over the years how to stop high inflation. It is not possible to fine tune inflation exactly but there is a big difference between inflation rising above 2% (the unofficial target rate) toward 3% and a rate of 10% or 15% where we would be in dangerous 1970s-style territory.

The arguments about QE are essentially about the cost-benefit analysis. Nothing in the complex, uncertain world of macroeconomic policy is risk free. But we know that the cost of unemployment is very high: family breakdown, mental illness, loss of skills, demotivated workers who drop permanently out of the work force. So the Fed has concluded that the cost-benefit balance is in favour of further unorthodox measures, including buying not just government bonds but mortgage backed securities which are indirectly financing housing purchases.

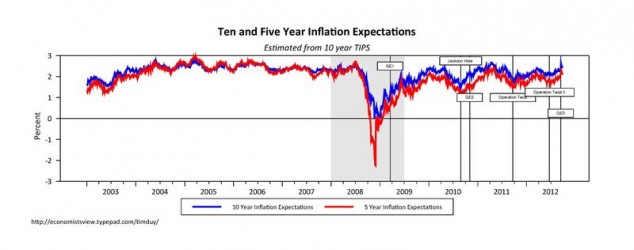

But there is no evidence of even modest inflation yet

Is there any evidence of inflation rising as a result of QE? Currently the evidence is pretty much zero. A recent post by Fed watcher Tim Duy is very helpful here (I found this from the even more useful blog Economist’s View, written by Mark Thoma, a professor at the University of Oregon). Tim shows that:

i) commodity prices (often seen as a indicator of global inflation) were rising well before QE and the rise following QE looks very much like part of the economic recovery following the financial crisis; it’s hard to see how QE can be causing global inflation via commodity price inflation.

ii) market expectations of future inflation, which can be inferred from the return on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), are still below 3% on five and ten year view and have barely moved during the period of QE. This is shown in his chart:

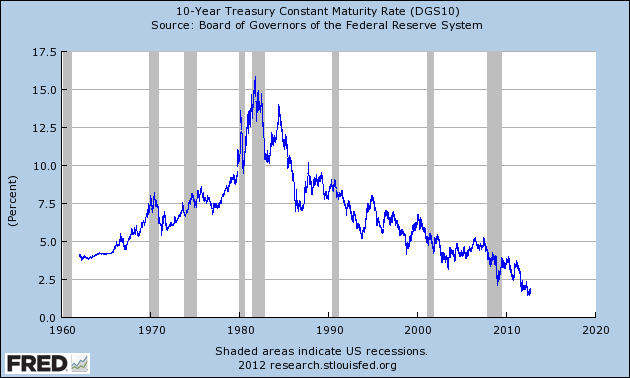

This is not to say there is no risk of inflation. But many critics have been arguing for three years now that large US deficits and the policy of QE and the accumulation of US government securities on the Fed’s balance sheet would lead to inflation and higher long term interest rates as foreign investors lost confidence in the soundness of the US financial system. But so far, long term interest rates have fallen, to historic lows (see below, where you can get a long term historic perspective on today’s remarkably low rates). Low rates have continued even after the Fed stopped buying so many government bonds, which of course casts doubt on whether QE has achieved much, but it is hard to see how it has done harm.

So the Fed’s cost-benefit analysis seems reasonable at present.

Further reading

There is a very nice chart, with data, showing the Fed’s purchases of various types of securities at the Cleveland Fed branch website:

http://clevelandfed.org/research/data/credit_easing/index.cfm

The Bank of England’s policy of QE is described at:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/Pages/qe/default.aspx

George

Great post Simon just a minor correction in your otherwise flawless piece is that ex Republican presidential candidate Ron Paul has called to “End the Fed” in a book and would have done so had he had the chance of being elected, Rick Perry is the republicans’ running mate to Mitt Romney but has not called to end the Fed, the Republicans if elected would probably replace Ben Bernanke at the Fed.

Simon Taylor

I agree that Ron Paul wants to end the Fed but he hasn’t actually accused the Fed of being hostile to the nation’s interest (so far as I know). Rick Perry was the person who called Ben Bernanke’s Fed “treasonous” in August 2011, in an attempt to win support from Republicans to nominate him as candidate for the presidency, which of course failed. There is a link to an article on that matter in the blogpost.

George

Sure but Ron Paul is the “failed presidential contender” Rick Perry is the vice presidential nominee and was not a presidential contender!

Simon Taylor

“On August 13, 2011, Perry announced in South Carolina that he was running for the Republican nomination for President of the United States in the 2012 presidential election. On January 19, 2012, Perry announced he would be suspending his campaign for the Republican nomination, and initially endorsed Newt Gingrich but gave his support to Mitt Romney after the former suspended his campaign.” (Wikipedia)