Every country’s economic relations with the rest of the world are summarised in the balance of payments. This is divided into the current account, which records the flows of trade and income, and the capital account, which records the flows of financial assets and liabilities. Usually countries have a deficit on one and a surplus on the other. China has been unusual in recent years in having a surplus on both, which explained the very strong growth of foreign reserves. But the capital account surplus has now become a small deficit. This is consistent with the view that the foreign reserves, which have stopped growing, might shrink in future. It is also a signal of capital flight from China – the rich taking their money out for fear of the future.

The balance of payments

We have got so used to the relentless rise of China’s foreign exchange reserves that it ought to be news that they are no longer rising, being roughly stable recently at about $3 trillion. In fact China experienced an outflow of capital in the second quarter of 2012. The future appreciation of the renminbi can no longer be taken for granted. To explain what’s going on we need a bit of background theory on the balance of payments (BoP).

The BoP for any country is a record of its economic transactions with the rest of the world. Unless a country is a total autarky, meaning it is self sufficient or at least it chooses to have no dealings with the rest of the world, then it will have inflows and outflows of resources. (North Korea today and Albania during the 1980s are rare examples of near-autarky.)

Those resources are classified by economists into: i) goods, services and net income payments & receipts; and ii) financial resources. The first group of resource flows is captured in the current account and the second in the capital account.

The current account is often what people refer to when they say that a country has a balance of payments surplus or deficit. Germany, for example, routinely runs a current account surplus because it has a remarkably strong export industry. It imports things too but not to the same extent.

The UK and US have for several years run current account deficits, importing more than they export. Note that exports and imports here refer not only to physical (“merchandise”) trade but include services such as tourism, investment income and travel. The UK has had a deficit on its physical trade for many decades, at least until North Sea oil and gas came on stream, but most of the time it more than offset this with a surplus on the “invisibles” trade, meaning services and net investment income.

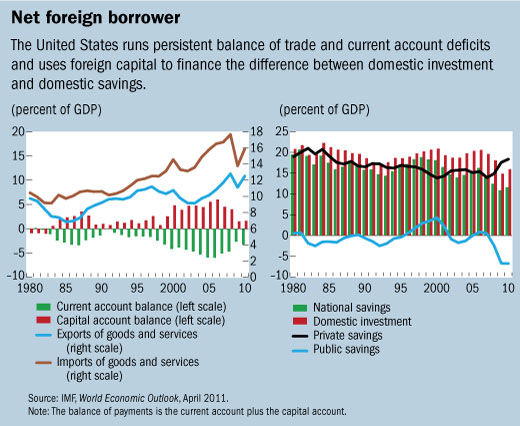

A country can’t run a current account deficit indefinitely because it has to be paid for, either by running up debts or by running down assets. Neither of these can be done forever. That’s why the current account is often the focus of attention in the balance of payments analysis. Here is the US position in the last decade.

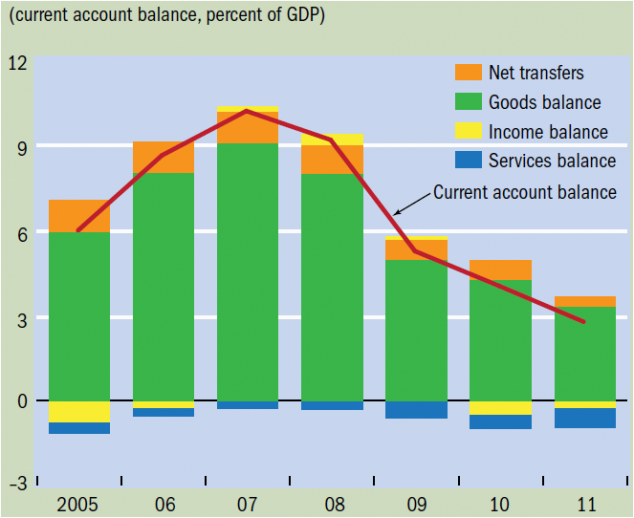

China has had a high current account surplus for many years, mainly driven by high export growth. This chart from the latest IMF Finance and Development shows the structure of the current account.

China’s once huge, but declining surplus on goods dominates the current account. Services trade has been regularly in a small deficit and flows of income swing between deficit and surplus over time. All of these surpluses and deficits must have counterparts in the rest of the world. China’s surplus on goods trade means an equally sized deficit among its trading partners, particularly the US.

The capital account

But the capital account matters too. A country may be a net recipient or payer of capital. If foreign investors are optimistic about a country’s prospects they may invest by purchasing shares or buying companies outright or by buying the government’s bonds. All of these represent an inflow of capital. This means a capital account surplus, in these cases of a benign kind.

But a country may borrow abroad to finance deficits and attract a capital inflow that does not reflect good economic prospects, merely a financial gap. Many Latin American countries ran large capital account surpluses in the late 1970s by borrowing from the big American banks. This was to allow those countries (chiefly Mexico, Brazil and Argentina) to keep their economies growing despite a huge rise in the cost of imported oil after the OPEC price hike of 1973-74. The US government encouraged the banks to keep lending, to maintain economic growth and stability in the western hemisphere. But after the second sharp rise in oil prices in 1979-80 following the Iranian Revolution, the level of debt became dangerously high. The US Federal Reserve put up interest rates to combat high inflation in the US and in doing so drove those countries into default in 1982, precipitating the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s.

The Latin American example shows how the two accounts are frequently linked economically. A capital account surplus pays for (finances) a current account deficit. If the deficit reflects the import of machinery and equipment that will raise future growth, this is good and sustainable. If it merely funds the import of consumption goods, it may not be.

Equally a persistent current account surplus country like Germany has a capital account deficit, meaning that it routinely exports capital by providing loans and funding to countries that want its exports. Some of this funding went to Italy and Spain, which ran (and still run) trade deficits with Germany. So Germany was directly helping to finance the trade imbalances it now complains about.

Many countries restrict capital flows. In the jargon, their capital account is not fully convertible. Economic theory and history provide a lot of reasons for having a relatively free current account, because free trade is often – though not universally – good for an economy. There is no such presumption in favour of a free capital account. Premature opening of East Asian countries’ capital accounts is widely seen as an important cause of the Asian financial crisis of 1997 (see here for a recent argument against India liberalising its capital account).

Netting the capital and current accounts

The overall balance of payments is the sum of the capital and current accounts. The sense in which the two balance each out depends on the country’s exchange rate regime. In the rich countries which let their currencies float entirely according to market forces, the overall demand and supply for foreign currency are equalised through the price – the exchange rate. So the capital and current accounts must in total sum to zero (other than quite significant data errors). The US, UK, Eurozone and Japan (most of the time) don’t try to influence their exchange rates.

Most emerging economies do manage their exchange rate by intervening in the foreign exchange market. Any surplus of supply of foreign exchange over demand, whether from a current account or capital account surplus, would tend to push the price of the domestic currency up relative to foreign currencies. If this is not what the government wants, it instructs the central bank to fill the gap by absorbing that surplus foreign exchange supply. How? It buys the foreign exchange with printed domestic money. It thereby acquires foreign exchange reserves. This has been the Chinese case for a decade.

In the opposite case of trying to keep the exchange rate up, because there is a surplus of demand of foreign currency, the central bank can use its reserves to fill the gap, preventing what would otherwise happen, a fall in the value of the domestic currency versus foreign currencies.

Why manage the exchange rate? It is one of the most important prices in the economy and rapid changes can have a destabilising effect on the country. So many countries intervene regularly to influence the daily exchange rate. Some try to fix it completely against say the US dollar (as in Hong Kong) or against a basket of currencies (Singapore).

In sum, the relationship is:

Current account + capital account + net change in foreign reserves = zero

In floating exchange rate countries the net change in reserves (*) is zero and the two accounts are brought into balance by changes in the exchange rate. In managed or fixed exchange rate countries any imbalance between the current account and capital accounts is met by raising or lowering reserves. If reserves are zero and there is an overall deficit the country has no choice but to let the exchange rate fall, or restrict capital flows and risk a black market in foreign exchange.

China

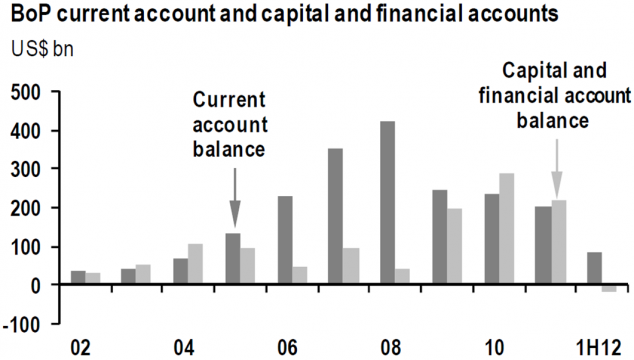

China’s decision to prevent the renminbi being pushed up in value against foreign currencies is what explains its massive foreign exchange reserves. The upward pressure has resulted from a combined current and capital account surplus, as shown in this chart from JPMorgan’s economists.

The sum of the vertical bars is the total surplus of supply of foreign exchange over demand. Left to the market, that would have pushed up the renminbi, possibly 20-30% on some estimates, choking off Chinese exporters’ competitiveness and pushing down the trade balance. This is what critics abroad, notably in the US, mean by currency manipulation, implying that China has rigged the trade market in its favour by keeping its currency at an unfairly low level.

The chart shows that the current account surplus has been falling but so has the capital account surplus. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange recently revised down its estimate of the capital account deficit for the second quarter but the downward trend is still marked. If China’s trade surplus keeps shrinking, because of weak demand in rich countries suffering recession or slow growth, and capital is now flowing out of China, then the net balance could become sharply negative.

Then the central bank, the People’s Bank of China, would have to choose either to use its reserves to fill the gap, keeping the renminbi up, or to let market forces push the currency down. Slowing growth in China is likely to cut its imports, so that the trade surplus may grow again. But the days of dramatically rising foreign exchange reserves are over for the moment.

The capital account is the sum of long term and relatively stable flows such as foreign direct investment, (FDI, foreign companies buying assets in China and building new factories), and more short term, volatile flows known as “hot money”. Although China restricts such flows it is very hard to block them completely. FDI remains strongly positive into China. It is widely suspected that the reversal in the capital account reflects the movement abroad of money by the Chinese rich, ahead of the change in government next month and the associated uncertainty. If the new regime appears stable and calm, perhaps some of this money will return. But if not, the outflow could accelerate, which will put pressure on the renminbi exchange rate. At least that would stop the Americans complaining about unfair trade.

(*) Postscript

The US and UK do have foreign reserves, but don’t use them for exchange rate intervention. The US also has 4,600 metric tonnes of gold at its Fort Knox base in Kentucky (that’s about 2.5% of all gold ever mined). Even larger amounts are held at the Federal Reserve Bank of NY in Manhattan, but much of that is held in trust for foreign governments.

This was the subject of the early James Bond film, Goldfinger, which featured a brilliantly evil plan to explode a dirty nuclear bomb at Fort Knox, rendering the gold useless with radioactivity for decades. (In the film, Bond at one point somewhat implausibly appears to know the half life of an isotope of cobalt). This would raise the value of the gold held by the mastermind Mr. Goldfinger, who was either Swiss or German but perhaps should have been French given that country’s historic attachment to gold. Where did he get the atomic bomb? The People’s Republic of China.

Further reading

The IMF BoP manual:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/bop/2007/bopman6.htm

An IMF briefing paper on liberalising the capital account http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/capital.hrtm and on potential problems with current accounts http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/current.htm

Ketil Widerberg

Thanks for this -miss your lectures. Ketil Widerberg MBA 2008

Chloe Miller

Thanks for this–writing a term paper for an international macroeconomics class at sciences-po university in Paris and this made everything much clearer

Octavio

Thanks for clarifying and helping me to understand each account and their importance, especially what makes them change. I need to write an essay about Chinas’ accounts balance, current and capital, at the University of Phoenix Los Angeles, California Campus

Al Arshad

If the balance of payment has to balance, by definition, and if China runs surpluses in both capital and current account, how is its BOP balanced?

Simon Taylor

The balance of payments is the total sum of domestic resident payments abroad and foreign non-resident payments into the economy. If there is no government/central bank intervention in the market (US, UK, Eurozone and most of the time Japan) then demand and supply will be matched by the price mechanism i.e. the exchange rate. In the case of China a few years ago and to a lesser extent now, the central bank does intervene. The balancing item is the change in foreign reserves held by the central bank. So if there is a surplus on both capital and current account then it means a corresponding increase in the foreign exchange reserves of the country.

OD

hello,can you PLEASE rewrite this paper with more outdated information and statistics about China

OD

Sorry I mean not outdated, but the new

Simon Taylor

This post covers the very different situation that China is now in: https://www.simontaylorsblog.com/2015/09/21/is-a-market-determined-exchange-rate-always-a-good-thing/

faziyamt

please how did the government uses it reserve to balance the bop?

Simon Taylor

The balance of payments is the sum of total demand for and supply of foreign exchange for an economy. It must balance in the sense that there can’t be a transaction without a buyer and a seller. If there is no government or central bank intervention then the balance is done by the market, with the price (the exchange rate) adjusting to make sure that demand equals supply. If the central bank intervenes it either buys or sells foreign currency to change the market rate. China used to buy foreign exchange to keep the price of the dollar higher than it would otherwise have been (and so the Yuan was lower). In the last 18 months it has been doing the opposite, selling its foreign reserves to buy Yuan, to keep the Yuan higher than it would otherwise have been. The reserves peaked at $4 trillion and are now about $3.1 trillion. The fall represents buying of Yuan in the markets using the reserves to pay for it, thus adding to demand for Yuan and supply of foreign currency.

D

Hi Simon. You wrote “if there is a surplus on both capital and current account then it means a corresponding increase in the foreign exchange reserves of the country”

But would that not mean that all the variables in the below formula would be positive, so how can they equal zero?

“Current account + capital account + net change in foreign reserves = zero”

Simon Taylor

Not all of them can be zero at once. If the first two are positive then the third must be negative. A rise in foreign reserves is a use of foreign exchange so it’s a negative item. You can think of the foreign exchange coming into the current and capital account and then going out to the foreign exchange reserves.

jenny

Could you please explain 2 reasons why a current account surplus is good for China and 2 reasons why a current account surplus is bad for China.

Simon Taylor

A current account surplus is neither good or bad in itself. It arises from a country having total savings in excess of total investment. That is more likely to happen in a mature, ageing economy (such as Germany or Japan) where large numbers of people are saving in anticipation of retirement. It it less likely in a developing economy where we might expect a high level of investment demand (because of the opportunities for development) relative to saving. China has been unusual in having very high levels of both saving and investment. It appears to be gradually moving towards a small current account deficit (according to the IMF’s forecasts) which would be more “normal” for a developing economy. By contrast the US, which one might expect to run a surplus, has been running a deficit for years. This is partly a result of the dollar’s reserve currency status (which means a lot of funding flows into dollar assets, leading to a capital account surplus and therefore necessarily a current account deficit). But it is also a result of the US household sector having a low savings rate, which is at least partly because of stagnating income levels.