Australia is often known as the lucky country. Not that all of its history has been lucky but in the last twenty years it has been one of the largest beneficiaries of fast Chinese economic growth. About a quarter of Australia’s exports go to China and its abundance of raw materials such as iron ore and coal have helped Australia to a remarkable 21 years of continuous economic growth.

But that happy picture is now clouded by China’s slowing economy, which is causing a fall in commodity prices, particularly iron ore, demand for which has been curbed by the slowdown in real estate construction, which uses a lot of steel. According to Bloomberg, the consensus still sees positive growth for Australia in the next couple of years but there is widespread concern about the structure of the economy, as manufacturing has been squeezed by the high exchange rate caused by booming raw material exports.

I came across this interesting report on the Australian economy from the firm Variant Perception, featured on John Mauldin’s essential investment blog. They see Australia as suffering from a form of Dutch disease. This is a term from the 1970s which is perhaps not so familiar now, yet it is quite relevant in a world where many countries have seen their economies boosted by high natural resources exports.

The Dutch disease is what can happen to an economy that enjoys a natural resource boom, either from the discovery of new resources (natural gas in the case of the Netherlands) or from a sharp rise in prices. The higher income from these resources raises economic value but it also pushes up the exchange rate and that makes other tradable sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, less competitive. The effect is that the new resources partly crowd out the old. Although the economy is overall larger there can be problems of employment. Manufacturing employs a lot more people per unit of output than natural resource extraction. If the process is swift it can cause unemployment, often regionally concentrated.

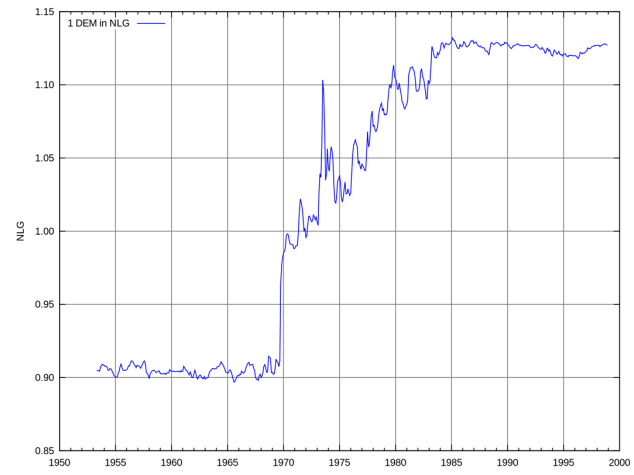

The rise in the Dutch exchange rate was pretty dramatic. This graph (from here) shows the Dutch Florin against the German Deutschemark from 1950 to 2000 (note that exchange rates were fixed until 1971 and that the price of oil, which dominated the pricing of gas, quadrupled in 1973-74).

There is also the fear of re-adjustment when the resources run out or prices fall. In principle a reverse process of exchange rate depreciation should help boost manufacturing exports. But markets don’t work that well and once companies have shut down production in a country it is hard to get them back.

Note that the Dutch disease is different from the “resource curse”, the idea that less developed economies can end up worse off after natural resource discoveries because the scramble to capture the new wealth leads to corruption and a predatory state. Some get rich but the majority are worse off than before. This is an often true story of political economy, avoidable only if the conditions for a non-predatory state are present. Foreign action to reduce the corruption in resource economies has helped in some degree here, through the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (the next meeting of which is hosted by Australia in May 2013). Examples of the resource curse in action are given in Acemoglu and Robinson’s fascinating book Why Nations Fail, though they emphasise that the roots of predatory states were usually there before the natural resources were discovered. (Their blog is excellent, continually refreshing their arguments and adding new examples, such as South Africa, about which I will write soon.)

Many countries have suffered in some degree from the Dutch disease. The UK saw a huge increase in its exchange rate in the early 1980s when it became clear how big the income from North Sea oil was going to be. This allowed the British government to repay early the loan it humiliatingly took on from the IMF in 1976. But, reinforced by the high interest rates of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s disastrous experiment in monetarist economic policy, the high exchange rate caused a near 20% fall in manufacturing and the largest peace time recession until the current one. Now that North Sea oil and gas are dwindling and are relatively unimportant for economic growth and taxation, the exchange rate has duly fallen (which couldn’t have happened if the UK had been in the Euro, one of several reasons why the UK was right not to join). But British manufacturing, excellent in quality, is small in scale and has a huge job to grow to a scale that will replace the long term push to GDP we enjoyed from oil and gas.

The boom and bust of the City of London can be seen as a sort of Dutch disease effect also. Financial services grew to a much larger proportion of the UK economy than any other rich country (excluding Luxembourg, which is largely a site for intermediation but where relatively little employment is created in finance). This boosted exports of services and helped to fill the UK’s trade deficit in manufactured goods. But the City over-expanded and it’s not clear what its long term contribution to GDP can be. Critics argue that not only did it push up the exchange rate above what was healthy for the rest of the economy, but it distorted and damaged the manufacturing sector by focusing on complex and socially useless financial products as the expense of the basic need of capital for British companies. (A variant of this argument has been made about the City of London since the late nineteenth century, but there is some force in it according to the recently released and highly readable Kay Review of short termism in the City).

One response to the risk of Dutch disease is to set up a sovereign wealth fund. SWFs are usually justified on the grounds of intergenerational equity – the resources will only last a while and some of the income should be saved so that future generations will benefit too. But they can have a benefit to the exchange rate. The mechanism of the Dutch disease is that there is a large increase in foreign exchange earnings (most commodities are priced in dollars). That pushes up the price of domestic currency relative to say dollars, meaning the exchange rate rises. Concretely, foreign companies seeking to pay domestic taxes must sell dollars to buy local currency. Left alone the market causes the price, the relative scarcity, of domestic currency to rise. A SWF or a central bank acting as exchange rate stabiliser, can take the dollars and deposit them in a fund, in effect taking away the demand/supply imbalance. It must still create the domestic currency that the foreign company needs to pay its taxes and that can lead to inflation. So a normal counterpart to this is either to raise interest rates, which risks damaging local manufacturing, or to mop up local currency through the issue of bills and bonds. But eventually that too risks pushing up interest rates as a steady increase in the supply of bonds must eventually mean a fall in their price (a rise in interest rates).

It’s impossible to accommodate a natural resource boom without any adjustment. There must be some shift of real resources in the economy but it is not necessary for this to be a zero sum game, nor even for manufacturing to shrink. Australia has a modern, advanced economy and careful macroeconomic policy should help limit the long term cost to the non-resource sectors of the iron ore boom. That requires skill as well as luck.

Further reading: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/dutch.htm

Leave a Reply