I see my job as trying to understand what is going on in the world of economics and finance, mainly by reading the research of others, and communicating it as best I can to others. It’s a privilege of my job that I have the time to read some of the fascinating books produced by academics and other writers, who are trying to make sense of the changing times we live in. In this post I will briefly describe five books I have read in the last few months which I think tell us something helpful, based on thorough research and analysis.

Most of these books are relevant to the EMBA elective I teach next month, titled “Brexit, Trump and the backlash against globalisation”. I first taught this course last year and much of the content remains relevant, but a year on we have a lot more information about the state of the US and of Europe, and the causes of “populist” reactions to the conventional way of doing things. My interest is in explaining the deep causes of these political changes and very tentatively peering into the future.

The first book is “The Narrow Corridor” by the highly successful team of Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, who wrote the wonderfully interesting “Why Nations Fail”. Their latest book extends the thesis of the first, that it is institutions which largely determine the economic and political success of nations. While not quite so rich in historical detail as the earlier book, “The Narrow Corridor” is still both entertaining and insightful. The idea is that there is a narrow range of success between having too little of a state, which means a society cannot organise to create essential public goods, most notably defence and security; and too much of a state, meaning a parasitic system that creates political tyranny and discourages economic progress.

As with their previous book, the one example that doesn’t fit too well is China, which is clearly a relatively despotic state by the authors’ standards, but so far has produced remarkable economic prosperity. It remains to be seen whether China in the long run proves a successful counterexample to their argument for an essentially liberal democratic outcome as the only one that can survive in the corridor.

It is now conventional wisdom that economic inequality and a sense of injustice leading to people and regions being “left behind” was and is a major source of anger in both the US and Europe, including the Brexit-supporting parts of the UK. Explaining why this came about is therefore very important. One perspective is that of the changing nature of technology in modern capitalism. Carl Benedikt Frey’s “The Technology Trap” provides a highly readable and persuasive explanation of much of what has gone wrong in the developed economies, especially the US.

Frey argues, with a lot of detailed historical analysis going back to England’s industrial revolution, that technology broadly comes in two forms: one replaces labour and leads to rising output but temporarily falling demand for (especially unskilled) labour. This was the case in the first few decades of the industrial revolution. Mechanisation lead to mass misery for English workers, whose standard of living fell for a generation. Early factories were designed to replace skilled labourers (including the famous Luddites, who smashed the machines that would take away their skilled jobs – they were quite rational in doing so from their own point of view). The new machines could use children, who were cheaper and less likely to revolt.

The second type of technology increases the demand for labour, and this is more characteristic of what is often called the second industrial revolution, based on the electrification of the economy and the mass industrial consumer good economy of the middle 20th century. Sometime called “Fordism” after Henry Ford’s pioneering mass production techniques, the big auto factories of the American mid-West (and in European countries) led to mass prosperity for relatively low-skilled labourers (men who had graduated school but no more). This was in some respects a golden age of capitalism because profits and wages both rose, more or less in line (though it was also a time when married women were still largely excluded from the labour force).

Unfortunately, the change in technology in the later 20th century has been back towards labour replacing, leading to a big fall in the need for low skilled workers, who are now forced into low paid service sector jobs. Even worse, the outlook is for a lot more of this: more and more tasks are likely to be done by machines or computers in the coming decades, meaning that while skilled workers in the knowledge economy may continue to prosper, everybody else faces falling pay or unemployment.

Torben Iversen and David Soskice’s “Democracy and Prosperity” puts this technological story into a wider context, arguing that the democratic capitalist economies evolve to ensure that the majority of voters support the changing economy, so long as they or their children are able to benefit from it. They argue that a lot of the value in the knowledge economy is bound up with combinations of skilled people in companies in places like San Francisco (or Cambridge) which cannot easily be replaced. Importantly, companies cannot easily just move to another country with cheaper labour because they cannot take the knowledge with them, as it is part of the local system of doing things. In othe words, the state has some power over these companies, unlike when earlier less knowledge intensive industries were free to move abroad to use cheaper labour.

The authors argue that the knowledge economy will be supported by a majority of voters, and the companies in it will support continuing state support for education, which is essential to supporting those economies. State research and development is another part of the mix. But they clearly acknowledge that a lot of people who lack education will not benefit from the knowledge economy and the political consequences of this could be destabilising.

“The Great Reversal” looks specifically at the way that the US economy has become more unequal and in many ways less competitive than that of Europe, reversing the pattern of 30 or 40 years ago. French economist Thomas Philippon, who is based at New York University, documents the effects of rising monopoly power (more expensive broadband and mobile phone bills, lower levels of new company formation) and persuasively ties this to the power of lobbying in the US, leading to a lack of enforcement of anti-trust regulation and the undermining of the previous dynamism of the US economy.

Technology and the rising power of money in politics are not mutually exclusive explanations of the fact that the US economy no longer works for the majority of Americans. The third cause is globalisation and in particular the “China shock”, which I have covered before. It seems increasingly clear that it is the first two which are probably the more important causes of the US economic and political malaise. In Europe it is more the technology that matters, though Europe has its own problems stemming from immigration and the uneasy relationship of the EU to nation states.

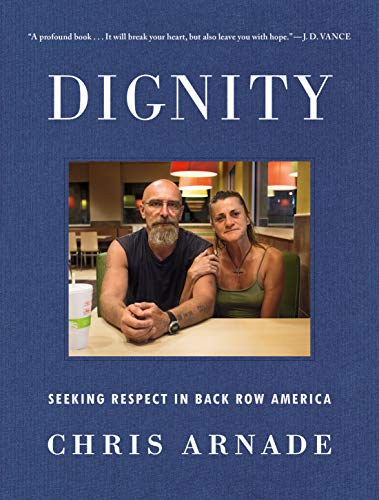

The human cost of the US economic changes is told with great sensitivity in a book titled “Dignity” by a former Wall Street trader called Chris Arnade, who spent several years visiting McDonalds stores across the poorer parts of the US, since this is where poor people now go, along with churches. He talks movingly of the reality of an absence of economic opportunity, powerfully reinforced by racism in some cases. But he also tells how, in the midst of great want, people nonetheless create community and hope. He contrasts the well-meaning attitudes of the well paid metropolitan educated liberal class (i.e. people like him – and me) who have been willing to move to advance their careers, with those who put their local friends and family first and still refuse to move from their hometowns, even when those towns are blighted by closed factories and decaying infrastructure. His book is a reminder that having an income and having a job are important, but not enough – dignity matters too.

Leave a Reply