Venezuela’s economic difficulties include very high inflation which threatens to become another example of hyperinflation. But what is this and why is it historically quite rare?

*

Inflation in Venezuela has recently been reported as reaching 46,000% with the IMF projecting it could reach 1,000,000% by the end of 2018. An article in The Spectator claims that the value of the maximum amount Venezuelans can take out of ATMs is equivalent to 12p in UK money (US$0.16). The Venezuelan government has devalued the bolivar and linked its value to its own cryptocurrency (*), which in turn is linked to the value of Venezuela’s oil reserves, the world’s largest. I think it’s fair to say that nobody outside Venezuela thinks this is going to do much to help. Venezuela’s economic crisis, which is rooted in politics, will not be resolved by anything as simple (or technologically clever) as this.

Inflation is very common in economic history and, while often unwelcome, is not necessarily a serious problem. Hyperinflation has been somewhat arbitrarily defined as a situation when prices are rising more than 50% per month (following the earliest serious study of the subject by an American professor Phillip Cagan in 1956. What really makes hyperinflation different from ordinary inflation is that it tends to lead to a collapse of the currency, a loss of confidence that shows up as an increasing unwillingness by the general public to hold any cash, ultimately leading to the use of other currency or even barter for economics transactions.

Modest and reasonably predictable inflation complicates economic life but is not necessarily a barrier to normal economic activity. If you know that inflation is and will remain 10%, you can make all the necessary calculations to ensure that the real value of economic transactions remains the same. Unions can bargain for higher wages, pension and other payments can be indexed to inflation. A steady state of constant inflation at 10% is not significantly costly compared with a steady state of 2% (which is approximately the official target for inflation in the UK, US and Eurozone). But ever accelerating inflation is a different matter. Not only does it become increasingly complex and costly to calculate and forecast inflation but the adjustments of prices to keep up become more frequent and difficult.

A Serbian colleague recently told me of the hyperinflation in Yugoslavia which took place in 1993-94 as that country began to disintegrate. He mentioned that as soon as people got paid they would hurry to spend their money before prices went up even further, a classic sign of hyperinflation. People in Serbia and Montenegro, the remaining states of Yugoslavia, started to use German Deutsche marks instead (Montenegro still uses the Euro, without permission, as its currency). An old joke from Latin America, which has had several episodes of high inflation over the last 60 years, captures the same idea. You know inflation is bad when it’s cheaper to take a taxi than a bus, because with a taxi you pay at the end (and the value of the currency has fallen).

Hyperinflation results from a collapse in confidence in the currency. This reminds us that all currencies depend on the confidence of the general population. Modern currencies are backed by nothing more than the good faith of the central bank that issued them (and the government that stands behind it). We all use a currency so long as we expect everyone else to use it. One anchor for any currency is that you can pay your taxes in it (this was how the early United States cemented the federal dollar as a national currency).

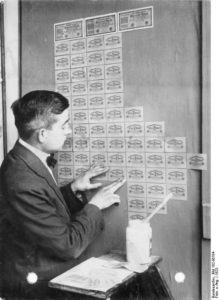

But if for some reason that trust is put in question, it makes sense to spend your currency as soon as possible and hoard some other currency or real assets or gold. Whatever the cause, if more and more people start to think like this then it is rational to behave the same way. Nobody wants to be left holding a pile of useless notes – and in a hyperinflation the notes can become so devalued that people use them as wallpaper (see photo below, Reichsmarks pasted on a wall in 1923).

The main reason for a currency losing confidence is that the state behind it loses confidence. Most hyperinflations result from a state or political crisis. “Ordinary” inflations can rise to costly levels but rarely mutate into hyperinflation. In the 1970s several of the developed economies suffered double digit inflation following the oil price shock of 1973/74, which certainly affected confidence in the economy, but did not lead to ever-accelerating inflation.

A typical hyperinflation results from a government spending more than it receives in tax and funding the deficit by printing money. Doing a small amount of this is not necessarily disastrous, but if it becomes clear that the government is systematically running unsustainable deficits and encouraging or forcing the central bank to fund them by printing money, then confidence in the currency will not last long.

The spectacular annual percentages of hyperinflations result from the magic of compound interest, described by Albert Einstein as the “eighth wonder of the world”. If we take the earlier definition of hyperinflation as monthly inflation of 50% and compound this monthly to get an annual rate, we get about 13,000%. That’s pretty alarming but nothing compared with what happens when hyperinflation really gets going. During the infamous German hyperinflation of 1922-23, the folk memory of which still haunts Germany government policy today, prices were estimated to be rising by 21% a day. If we compound 21% a day at a daily rate for 365 days we get an annualised rate of….1.6 x 1030%. That’s 1.6 followed by 29 digits (you get very different numbers depending on the rate of compounding but all the numbers are staggeringly high). The point is that 21% a day is not a stable rate of inflation, meaning that it cannot continue for long. The value of the currency is the inverse of the inflation rate; once prices are rising at anything like 21% a day, the decline in value quickly escalates towards a de facto value of zero (i.e. infinite inflation). People stop using the currency and turn to alternatives such as foreign currencies.

The record for hyperinflation is probably Zimbabwe in 2008. The peak monthly rate was estimated at 7.96 x 1010%, which means prices were doubling in just over 24 hours. The highest denomination notes were issued in units of 100 Trillion (1014).

Stopping hyperinflations

Hyperinflation is not only very inconvenient; it destroys the basis of normal economic activity. One of the key functions of money is as a unit of account, a measuring stick for the value of different goods and services. I sell my labour for money in the belief that I can spend the money to buy food, a haircut and a holiday at rates that are reasonably stable. If the measuring stick becomes unreliable it undermines people’s willingness to buy and sell things. Even worse, the collapse in trust makes people want to hoard whatever they can in other assets that will keep their value. Those with wealth will try to put it into real assets (land, cars) or into foreign currency or gold. But for the majority of people this is not possible. The often meagre savings of the ordinary people are kept in currency so hyperinflation wipes out their non-human wealth. This is not just destructive but can lead to a profound sense of injustice, especially as the wealthy are much better able to protect their wealth. The anger of the middle classes in early 1920s Germany was in large part owing to their loss of savings to hyperinflation. The political consequences of that loss of trust in the system were to be very serious indeed.

Hyperinflations burn out sooner or later because people shift to other forms of currency. Zimbabwe legalised the use of foreign currencies in 2009, simply to recognise the reality that nobody would accept Zimbabwean dollars; they wanted South African Rand or US dollars or Euros, anything really other than the discredited and destroyed local currency.

One rare example of hyperinflation which didn’t result from state collapse or a serious political crisis was the Bolivian hyperinflation of 1984-85. Along with other Latin American countries, Bolivia suffered from a sudden increase in the interest rate payable on its high levels of dollar-denominated debt. As the economy fell into recession, the government replaced its falling tax revenue with printing money. causing hyperinflation. Inflation in 1985 averaged 11,857%. There are reports of a cup of coffee costing 12 million pesos and an airline check-in desk attendant spending 30 minutes to count the 85 million pesos needed for a plane ticket. This is an example of the transaction cost of hyperinflation short of the actual collapse of the currency. Bolivia had the advantage of a parallel currency, namely the US dollar, large amounts of which circulated owing to the export of cocaine to the US.

What is notable about the Bolivian case is that a team of economists including Jeffrey Sachs, famous as the head of the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York from 2002-2016, helped the government bring the hyperinflation rapidly to an ed. Sachs and his colleagues advised a new government, elected in August 1985, on the New Economic Policy, which restricted spending, partially floated the peso and created the conditions for renewed confidence in the government’s economic policy and the currency. The hyperinflation stopped just three days later. Collectively Bolivians shifted from the “bad equilibrium” of treating the currency as untrusted, to the “good equilibrium” of trusting it.

Sadly, such rapid solutions are historically rare. We can only wish the Venezuelan people the best of luck.

Yolanda Z

The underlying theory behind hyperinflation has always been the significant inconsistency between the supply of money and the value of taxation. This can be resulted from either the government itself over-issues currency to cover the requirement of national welfare, or the government relies on over-issuing currency for international trade. Germany, after the World War, used the Deutschmark to buy foreign currencies to pay for reparations (though I remain my opinion that France should be blamed for Germany’s hyperinflation to some extent).

However, I also notice that, based on what I have been acknowledged, the ultimate solution to hyperinflation is the same – replacement of new currency plus taxation reform.

Until shortly before the foundation of People’s Republic of China, between June 1946 and May 1949, domestic commodity price increased by 36 trillion times and food price increased by 47 trillion times compared with those of the prewar period (June, 1937), which were 248 times and 324 times higher respectively than the multiples of additional currency issuance. “100 Jin Yuan Quan (bills issued by the KMT government in 1948) for a grain” was the true portrayal during that period.

Back to Germany’s story, the Deutschmark depreciated dramatically. Before the war, Germany suspended the exchange of gold for the Deutschmark. This gave rise to two separate versions of the same currency in Germany, i.e the gold mark and the paper mark. Not surprisingly it happened again in China, where gold remained steady value whilst Jin Yuan Quan crashed into the trash (unfortunately the reservation of gold was largely transferred away with the KMT government, which made it even more difficult to reform the whole economy. But this was another story.) The PRC government had to replace Jin Yuan Quan with a new currency, as well as establishing a new taxation system. But slightly different from normal solution, except for Chinese Yuan (the old-time currency differs from what we’re currently using RMB), the government forced to use grain coupon, oil coupon etc. to control the essential commodity. Each coupon represented a standardized amount of commodity. I think it was not a good solution to hyperinflation but was an extraordinary move under that circumstance.

I’d better stop here, though I still have a lot to say lol

The interesting part of finance is that we could always find similarities from the past hence we could be able to predict the future and give possible solutions. The more interesting part is that we cannot simply use the past experience to solve all the problems since each individual case has something special.

BTW the problem of China is quite complex. I believe there has already been hidden abnormal inflation to some extent. But luckily, we have seen some brave steps taken recently trying to solve the problem.

All the best wishes to both Venezuelan and China.