Exchange rates are among the most important macrofinancial prices, influencing many aspects of an economy. This post introduces exchange rates and their importance for macroeconomic adjustment

*

What is an exchange rate?

An exchange rate is a ratio, the price of one currency relative to another. All prices are ratios, but normally they’re expressed in terms of the local currency (the price of bread = £1) and we don’t think of them as such. “The” exchange rate is really lots of rates. The pound has different rates versus the US dollar, Euro, Swedish Krone, Japanese Yen and so on. Each of these rates changes constantly as buyers and sellers of the currencies are matched through foreign exchange (FX) markets.

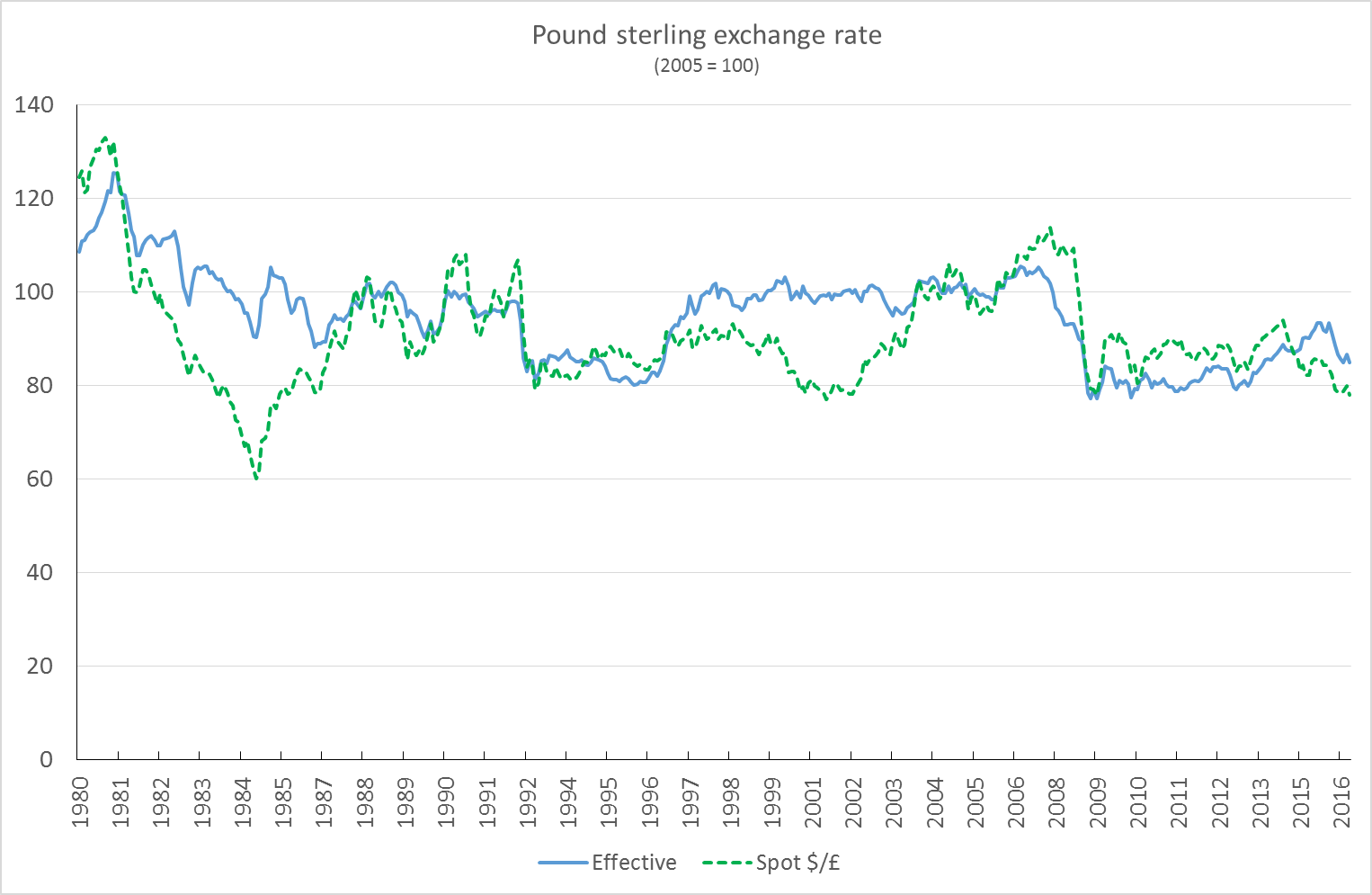

But we can talk about the overall exchange rate, meaning the average of these ratios, usually weighted by the amount of trade a country does with each of the other countries or regions (we call this a basket of currencies). So the effective sterling exchange rate is the average of the various rates against the UK’s main trading partners. This has to be expressed as an index, as it is not an actual price that can be observed directly.

It means that the pound might fall against one currency, such as the dollar, but rise against the basket of currencies. It’s important to keep these ideas separate, especially when the dollar is moving strongly against other currencies. In recent years people have tended to focus on the Chinese RMB rate against the US dollar. But with a rising dollar, it is inevitable that the RMB would fall versus the dollar. But against a wider basket of currencies the RMB has either not fallen much or even risen. In 2015 the Chinese central bank adopted a basket of currencies as an alternative guide to the exchange rate, for just this reason.

Over longer periods, the difference between a specific exchange rate and the overall effective rate can be more significant. The chart below shows the $/£ exchange rate converted to an index to make it comparable with the effective sterling rate. At times the two have diverged considerably, at times when moves in the dollar have been the main driver rather than moves in the pound.

Real versus nominal exchange rates

It’s also important to distinguish the real from the nominal exchange rate. The rates we observe in the markets are nominal, just as all prices we observe are nominal. But what matters for economic behaviour is the real exchange rate. This means adjusting the nominal rate for changes in the overall price levels in two countries for which we’re calculating the exchange rate.

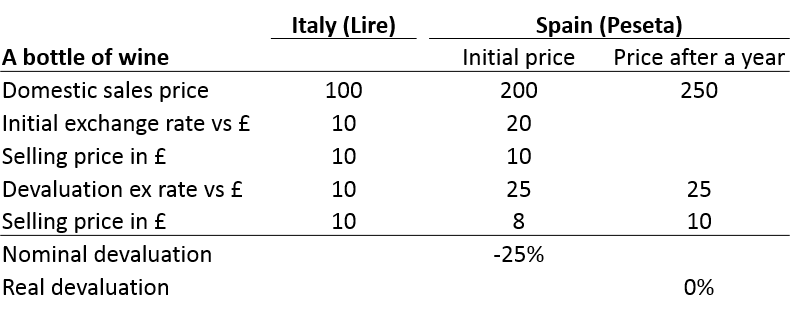

For example, lets assume that, before the Euro was created, Italy and Spain competed in international wine markets, including the UK. Let’s also assume that British consumers, lacking finesse in wine, simply buy the cheapest. Start with Italian wine priced exactly the same as Spanish. Now Spain, seeking to sell more, devalues its currency. This makes its exports cheaper in terms of sterling so the price in the UK market should fall.

In the example below, we assume the Italian Lire/Pound exchange rate is 10 and the Spanish Peseta/Pound exchange rate is 20 (the numbers are purely illustrative). If the Peseta is devalued to 25 to the pound (a 25% fall) then initially Spanish wine will now sell at £8 and the Spanish will outsell the Italian wine.

But if after a year Spanish domestic costs and prices rise, so that the cost of producing wine goes up by the same amount of the devaluation, then the overall effect will be to leave the export price unchanged. In the example below, we assume that the domestic price of Spanish wine rises from 200 to 250 (by 25%) The price in pounds rises back to £10, even at the lower nominal exchange rate. In this case the nominal exchange rate devaluation is fully offset by domestic inflation, leading to no change in the real exchange rate.

This may be a slightly extreme case, but there is plenty of evidence that nominal devaluations (and appreciations) may be partly or even completely offset by domestic price changes. In the long run it is real exchange rates which matter.

Fixed versus floating rates

Exchange rates can be set by free markets (“floating” rates) or by governments (“fixed”). The rich countries largely leave their exchange rate to the market. They don’t usually attempt to influence the level, nor they do intervene by buying or selling currencies. Most emerging economies either fix their exchange rate, typically to the dollar (this is known as adopting a dollar “peg”) or they have a target range and intervene if the currency moves outside this range. Partially leaving the rate to market forces is sometimes known as “dirty floating” meaning that the government retains the right to intervene when it deems it necessary.

The case for floating rates is the same as for any other free market: the free play of demand and supply is more likely to deliver the economically most efficient level than governments. The case for fixing or at least some intervention is that the exchange rate is the single most important price in the economy and if that price is volatile or appears to be far away from what is justified by economic fundamentals, then governments have a right and duty to intervene. The case for intervention is stronger for emerging markets where the exchange rate may be distorted by the decisions of foreign investors looking at global (mainly US) factors. Smaller economies can get carried up and down by tides not of their making.

But it’s not just emerging economies which make the case for intervention. The Euro currency represents the ultimate fixed exchange rate and its creation in 1999 followed 25 years of attempts to limit the volatility of European exchange rates.

What drives the level of the exchange rate?

Economic theory provides a lot of support for what the sustainable or fundamental exchange rate should be. Unfortunately actual rates can deviate considerably from these theoretical rates, in part because any theory must be calibrated with estimates of the macroeconomic fundamentals and these are open to reasonable disagreement. Moreover economists disagree to some extent about the theory itself. But there are some broadly consistent attempts to define what are called fundamental equilibrium exchange rates (known as FEER – not an ideal acronym). An estimated FEER is the exchange rate at which an economy is in equilibrium, which means that trade flows and debt are on sustainable paths. Different models of the economy will produce different FEER estimates so there is no precision about FEERs. But they can give some idea of when exchange rates are markedly far from their fundamentals.

William Cline of the Peterson Institute of International Economics (PIIE) estimated in May 2016 that the US dollar was about 7% over-valued relative to FEER. The IMF estimated in June 2016 that the overvaluation was more like 10-20%. So we might conclude that the dollar is probably overvalued but the scale is open to dispute.

Unfortunately exchange rates can diverge for years from their FEER so that is not a good guide to short or even long term exchange rate changes. For those currencies set entirely by market forces (essentially the rich economies) the exchange rate is set continuously by demand and supply. At any moment of the day, somebody somewhere is buying and selling dollars for pounds, euros etc. The flows can come from transactions – for example the need for a UK-based importer to pay a supplier in dollars, meaning selling pounds to buy dollars.

But the overwhelming volume of daily flows comes from capital movements. Banks, asset managers, sovereign wealth funds and emerging economycentral banks are all playing in the markets each day both to hedge their risks and to try to take advantage of expected currency movements. This produces a vast flow of fast moving or “hot” money which can push exchange rates around on the basis of actual or rumoured data. In particular, expected short term interest rates drive flows of funds. A hedge fund might buy dollars because it expects interest rates to rise more there owing to the relatively greater strength of the US economy. But the longer term strength of the US economy is possibly being reduced by an overvalued dollar. If the Federal Reserve takes a longer term view it might not raise rates so quickly, precisely because of the higher dollar caused by the original expectation of higher rates! Foreign currency traders are constantly weighing these sorts of considerations up to guess what the next move will be.

One result of the constant attempts by thousands of investors to forecast exchange rates is that all available information will already be reflected in the market, so rates will tend to be unforecastable – they will follow a random walk. There is some evidence for this being an accurate description of short term movements, which is one reason by asking an economist for advice on when to convert your holiday money is usually futile: they either don’t know or will fall back on the random walk argument to avoid offering any useful advice.

While the advanced economies almost entirely leave exchange rates to the market (there are exceptions such as the Swiss National Banks’ attempt to keep the value of the Swiss franc down in 2009) many emerging and developing economies manage their exchange rates. This means they intervene to change demand and supply, using restrictions on fund flows into and out of their countries to do so. Without restrictions there is little that central banks can do to influence the market. So the Chinese government restricts flows into and out of China, providing some room for the central bank to influence the exchange rate. But there is a limit to that power because there are large gaps in the controls and a lot of RMB is now traded outside mainland China, mainly in Hong Kong. Indeed there is a separate exchange rate for the onshore (domestic) RMB and for the offshore. The fact that differ shows that there is not yet a free market in RMB. Longer term the stated Chinese government policy is to allow complete freedom, meaning it would leave the exchange rate entirely to market forces. But quite when that might happen is far from clear.

What happens when a currency falls in value?

When a currency falls in value owing to market forces we talk of a depreciation. If it’s a deliberate decision by a government which controls its currency we tend to say it’s a devaluation. Either way, let’s assume that the pound has fallen against a basket of currencies, as happened after the Brexit vote. What does this mean? We can think of the effect on UK consumers and the effect on international trade.

From a UK consumer’s point of view, the change in prices has, like any change in price, an income effect and a substitution effect. A fall in the exchange rate will push up the prices in sterling terms of imported goods and services. So prices in the UK will tend to go up. How much they rise will depend on: i) how much of UK consumption is based on imports rather than home supply; ii) the extent of competition in the market – if there is a lot of surplus capacity then prices may not rise as importers fight to retain market share; iii) the extent to which people are able to shift to domestic sources of supply.

But the overall effect on consumers is at best neutral and probably negative, if only because foreign travel must get more expensive (it costs more to go on holiday than before). People may choose to holiday at home instead, but their opportunities are worse than before, for a given income.

So the income effect is generally negative – consumers will on average be worse off than before and will probably consume less. The substitution effect will encourage them to spend less on the relatively more expensive goods and services (those imported or linked to import prices) and spend relatively more on relatively less expensive goods and services (those with a low import content or which are unaffected by import costs). One effect of this might be to spend more on domestically produced services, whose price should not change much. And to spend less on imported manufactured goods or on foreign services such as tourism abroad.

For businesses engaged in international trade, the fall in sterling makes exports abroad cheaper, assuming that the exporter keeps its sterling prices the same (it could raise them by the extent of the currency fall, leaving its foreign currency selling price unchanged). British businesses will be incentivised to export more because it has become more profitable or they can sell more at the same price. Foreign exporters to the UK will be less competitive than before, meaning that they either have to cut their prices to retain market share or they must accept a lower profit margin.

These import and export effects are qualitative – the direction of the effect of the exchange rate is broadly predictable. But the scale of the effect is an empirical question. Here we have to use the concept of the price elasticity, the degree to which demand or supply changes relative to a change in price. Some imported goods may be very price elastic, for example the demand wine from Italy which competes with Spain will be highly sensitive to small changes in their relative price, assuming that the quality is the same. But a country which imports oil may show low price elasticity, meaning that even quite a large rise in the price of oil may not cut demand much, because there is not much scope for substituting for oil.

So the actual effect on trade of a devaluation or depreciation is not predictable without information about the structure of the economy and the extent to which the domestic economy can substitute for imported goods and services.

Effects on wealth, distribution of income, inflation

If we consider the effects of depreciation on consumers and on firms we can deduce that it redistributes income from households to firms. Consumers are worse off after a devaluation because at least some of what they buy has become more costly (the income effect). But businesses are generally better off if they export or benefit from a shift in spending away from imports (the substitution effect). So the effect of depreciation on the national income distribution is to raise profits and cut real incomes. This may not be obvious at first, but is to some extent the point of a devaluation intended to correct macroeconomic imbalances. If there is an excessively large balance of payments current account deficit, it can be seen as reflecting too much spending by the household sector. A devaluation curbs household income and forces lower spending.

Recall earlier the illustration of real versus nominal exchange rates. Why might a nominal devaluation be followed by a general rise in prices? This is likely to some extent, because a devaluation puts up the prices of all imported goods and services. This means some things become more expensive directly, because they’re imported. But it also allows domestic producers of similar goods and services to raise their prices, since they face less price competition than before. The combined effect gives rise to a general rise in prices – inflation.

If there is rapid inflation following the devaluation and if there is resistance by labour unions to the cut in incomes which a devaluation necessarily brings, then we may face a price-wage spiral, which leads to such an increase in overall wages and prices that the benefit of the original devaluation is completely offset. Indeed it may lead to a further devaluation and a spiral of falling currency, rising prices and general macroeconomic instability. Something similar to this happened in the UK in the 1970s. It was only stopped by an emergency loan from the IMF to the British government, conditional on a cut in public spending to improve the government’s financial deficit and to reduce overall demand in the economy, to curb inflation.

Note that if we reverse all of this, and consider an exchange rate appreciation, it implies a cut in inflation, as import prices fall and domestic companies face more competition from abroad. One way to cut inflation then, is to drive up the exchange rate or keep it at on over-valued level. This is what happened in the UK in the early 1990s, when the pound sterling was linked to the German deutschmark. The policy was successful in the sense that inflation in the UK was indeed low. But it also kept the economy in deep recession, as UK companies were unable to compete effectively. When the link was abruptly broken in 1992, the economy started growing comfortably but with no increase in inflation, because there was plenty of excess capacity in the economy.

Internal devaluation

Another matter which arises from the concept of the real exchange rate is the idea of an internal devaluation, as in some Eurozone economies. Exchange rates can be floating or fixed. The ultimate fixed exchange rate is when you combine two currencies into one, as it is then impossible to have a nominal devaluation. Spain cannot any more devalue its currency against that of Germany because they share the same currency. But it can try to engineer an internal devaluation, meaning that it cuts wages and costs to achieve an improved competitive position relative to Germany. But compared with a nominal devaluation this is slow and painful. The very deep recessions that Spain, Portugal and Ireland suffered during the euro crisis period did lead to some improvement in those countries’ competitiveness. But it was at the price of very high unemployment and would have been much more fast and effective if it could have been done through devaluation of their currencies.

Long term prosperity from rising exchange rates: Germany, China

A nominal exchange rate devaluation brings greater competitiveness, at least unless domestic price rises partially offset it. So it sounds as if the way to economic success is to have a weak exchange rate that tends to keep depreciating. This is the exact opposite of the truth, which is that strong economies get into a virtuous circle of improved productivity, better competitiveness, stronger exchange rate and then further improved productivity. Countries which keep having to devalue their exchange rates to avoid their trade deficit getting too big face underlying problems with productivity and growth. Devaluing their exchange rates may temporarily help but cannot bring higher long term growth if those underlying problems remain.

FURTHER READING

Bank of England on concepts of exchange rate equilibrium

IMF on real exchange rates

IMF on choosing an exchange rate regime (fixed or floating)

Bank of England on research showing that flexible exchange rates do help speed of adjustment for developing economies

IMF research on the effect of the dollar on emerging economies

McKinsey on managing foreign exchange risks for corporates

Leave a Reply