What exactly is liquidity?

The word liquidity is used in many different ways, often confusingly. It’s important to keep clear the centrally important concept of what liquidity is: the ability to turn assets into money quickly and at low cost.

*

It’s common to read in the financial press that central banks are keeping up asset prices by creating a wave of liquidity. Commentators often refer to the movement of liquidity around the world, most recently from emerging economies to the advanced ones. Both of these uses can cause confusion.

In the first case, what the critics (typically hedge fund managers) really mean is that central banks have set very low (and now in some countries negative) short term interest rates, which by holding down borrowing costs can encourage the buying of assets, thereby pushing up their prices. This is of course exactly what the central banks intend to do, to encourage investment and greater consumer spending. But that is nothing to do with liquidity, it is just cutting the cost of borrowing.

In the second case, writers use “liquidity” to refer to the flow of short term investment funds from one country or asset class to another. For these funds to move easily, the assets in which they are invested must be fairly liquid, otherwise it would be slow or costly to sell them. But the fund flows themselves are not caused by nor should be described as liquidity.

Liquidity does have a clear definition, which has been an essential quality of a well functioning financial system for centuries. An asset is liquid if it can be turned easily, quickly and with minimal transaction costs into money – either cash or funds in a bank account. This is something of value to people using the financial system.

Physical money and bank deposits are the most liquid of assets. Other financial assets can be liquid if they are traded in well functioning markets in large quantities. So UK government bonds and the shares of major global companies are liquid because you can buy and sell them almost instantaneously at very low transaction costs.

Corporate bonds are less liquid because typically they are not frequently traded. Similarly for the shares of small companies. And private equity and real estate are very illiquid – they can be sold but usually only after a lengthy process and with significant costs.

Almost any asset can be sold quickly if you really need to but if the asset is illiquid, it can be sold fast only at the price of a large discount to the value you might get if you sold more slowly. The buyer can both take advantage of a distress seller and needs to be protected against the inability to do a proper asset appraisal (“due diligence”), so there is a risk that the asset is not what it seemed. Assets such as real estate or a private equity are illiquid.

Liquidity is a feature of assets that people value highly because we all want flexibility. If you have a sudden surprise that needs funding (illness, a distressed relative, a sudden tax bill) you need to be able to raise finance fast. If your affairs are in order you may be able to borrow at an acceptable rate, but sometimes that will still require you to pledge collateral. And banks prefer liquid collateral.

If you’re not in a position to borrow then you need to sell something. If you have a store of liquid assets then you can raise funds quickly without serious costs. If not, you may take a big hit on selling perfectly good but illiquid assets in a hurry.

What goes for individuals goes for companies and especially banks. One standard way of judging a company’s balance sheet is to look at the amount of short term assets and liabilities, meaning claims and obligations of a year or less. Within this accountants particularly look at very short term obligations and claims – what are your creditors expecting you to pay in the next month or two, and how are you going to pay for it? If your ability to pay depends entirely on your claims on other people – who may NOT be able to pay – then your liquidity is stretched and may put your whole business at risk.

Liquidity is a valuable quality and so people are willing to pay for it. Some assets are intrinsically liquid (chiefly money). In other cases, liquidity is provided by financial markets, chiefly by market makers. This is a rare case where the financial jargon accurately describes what it is. Market makers are people who stand ready to buy and sell assets at prices they publish or display electronically. If you want to buy oil, an interest rate swap or a corporate bond in reasonably large quantities, you will need to go to a market maker (perhaps via a broker, who provides the access to the market maker that you yourself lack).

Market making is extremely useful because it means that I can buy 100,000 shares in BP whenever I want, without having to wait for a seller of 100,000 shares to happen to be there to trade with me. Market making bridges the gap between buyers and sellers, ensuring that there is a market (the opportunity to buy or sell) at all times – or at least during trading hours.

Market makers are often given certain regulatory privileges in exchange for promising always to provide liquidity, though at a price of their choosing. This is a way to ensure there is always some liquidity available, whatever the state of the market. (This promise can break down though. In the October 1986 Wall Street crash, still the largest one day fall in a major stock market, market makers on the New York Stock Exchange, faced with a vast amount of sellers and no buyers, allegedly left their phones off the hook so they couldn’t be forced to buy even more stock.)

The liquidity premium

Since liquidity is valuable, people will pay for it. A share in a company which is traded on a stock exchange is worth more than one which isn’t. The former is public equity and the latter is private equity. Listing shares in an IPO raises the value of the otherwise identical shares because it brings liquidity.

This means that private equity investors need to get a return of 1-2% above their holdings of public equities, simply to compensate for the illiquidity. Typically a private equity fund ties up your money for up to ten years and you can only sell if there is a buyer and even then probably at a discount to the fair value of the assets.

Long term investors such as endowments and pension funds can put part of their portfolios in illiquid asset without difficulty, because they have a large enough pool of assets that they can accept the illiquidity. Mutual funds are not able to do this because they may face immediate redemptions by customers.

Certain types of long term, illiquid investments such as infrastructure naturally fit with those long term investors who should in theory get an extra return for their willingness to bear the illiquidity, which other investors cannot (so the initial price of the asset is lower than it would be if it were liquid).

During times of uncertainty or distress, individuals prefer more liquid assets, because it gives them more flexibility in their decision making. The liquidity premium rises and less liquid assets fall in value. A higher liquidity premium may therefore reflect increased risk aversion.

Banks and liquidity mismatching

For commercial banks (deposit takers) liquidity is central to the business model. Banks routinely run a mismatch between the liquidity of their assets (loans to companies and households) and their liabilities (deposits made by their customers).

Current account deposits are by definition very liquid – I can take money out of my bank account instantly via a debit card, online account or ATM. But bank assets are usually fairly illiquid – the bank cannot force me to repay my mortgage suddenly.

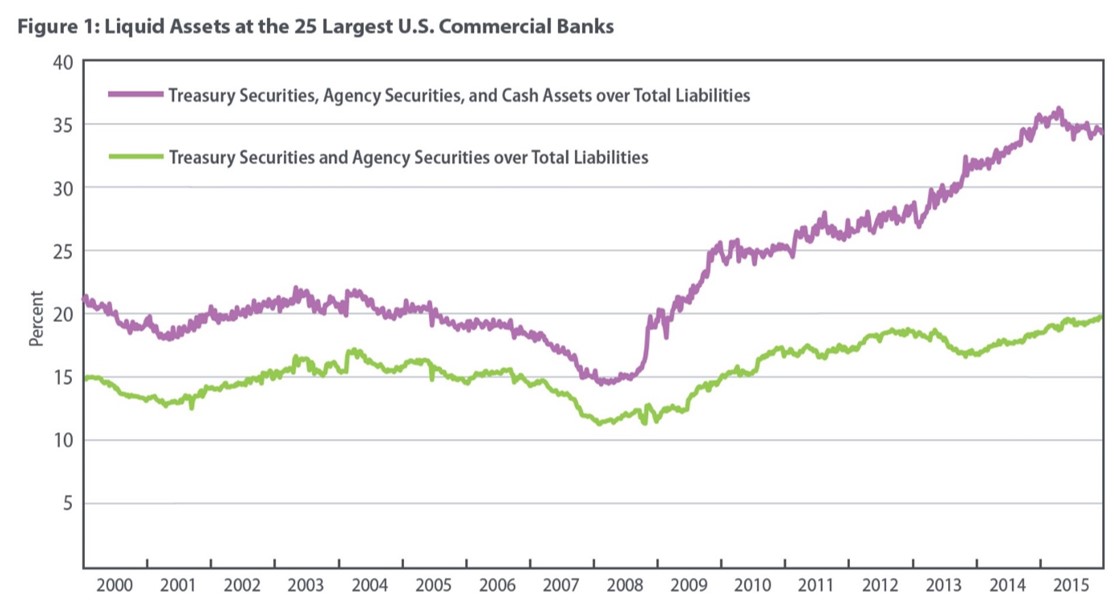

That liquidity mismatch is a source of trouble. History shows it has often brought down banks and led to contagion of other banks. Most countries now have some form of deposit insurance that reassures depositors that, even if the bank gets into trouble, they will get their money back, thus reducing the pressure to take out their money at the slightest whiff of trouble, thus bringing about a bank “run”. On top of deposit insurance, regulators also insist that banks limit the asset/liability liquidity mismatch by requiring banks to hold a certain proportion of their assets in liquid form. Usually this means government bonds, which (at least in developed countries) are usually liquid and safe.

The Basel III international bank regulatory agreement includes a Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) which requires banks to hold enough liquid assets (as defined by the Basel Committee) to cover 30 days of normal liquidity needs. So in theory a bank could lose access to it usual liquid funding sources but keep operating for 30 days, long enough for other solutions to be found.

This chart from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond shows the increased holding of liquid assets by the largest US banks in recent years.

This might work fine for a single bank in trouble. But if all banks suffer a liquidity problem at the same time the system may not cope, especially if everyone holds government bonds as their liquid assets. In a systemic crisis, all banks would have to sell their bonds, potentially causing a collapse in their price and jeopardising the very liquidity that such bonds are supposed to have.

The ultimate provider of liquidity is the central bank, a service known as the lender of last resort. Financial markets are prone to crises, sometimes taking the form of a liquidity problem. In late 2008 the collapse of Lehman Brothers led many people to doubt the financial security of all investment banks and most commercial banks. This was reinforced by the difficulty of knowing which banks had holdings of mortgage-related securities that were at risk of losing much of their value. The lack of transparency and generalised uncertainty led to a generalised unwillingness to lend to almost any bank. All banks therefore hoarded what liquid assets they had. The normal inter-bank funding market that allows banks to adjust for small daily gaps between funds coming in and funds coming out ceased functioning.

In this situation only central banks can provide liquidity and the Federal Reserve and other central banks did so. The US had no central bank until 1913; the recurring crises of liquidity which were only just overcome by private bank action (led by JPMorgan in the famous crisis of October 1907) made it clear that a credible lender of last resort was necessary to avoid the economic costs of financial crises.

Liquidity concerns today

Market making is a commercial activity which banks provide only if it’s profitable. It requires banks to provide balance sheet capacity (to bridge the gap between buying and selling). That in turn requires commitment of capital and brings a regulatory capital charge. Many banks argue that higher regulatory costs, in the form of a higher required proportion of equity funding of the balance sheet, has reduced the profitability of market making.

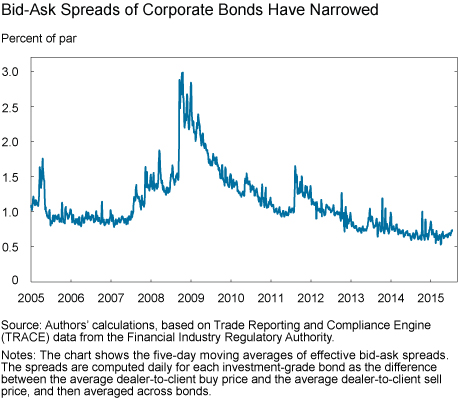

Some critics argue that this has reduced the overall market making capacity, thus reducing market liquidity. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York examined these claims in detail recently and concluded that market making capacity had indeed fallen but back to levels that were normal before the financial crisis, when capacity rose to unusually high levels. Their researchers found that normal measures of liquidity suggested that there was no fundamental lack of liquidity in markets. One way of measuring this is the bid-ask spread (or bid-offer spread) which is the gap between the prices that market makers buy at and sell at. On average this must be positive, to allow market makers to make a profit (at least on average). A narrow spread suggests healthy competition, consistent with profitable market making. This chart from the New York Fed shows that spreads on corporate bond market making rose sharply in 2009 as banks cut back on trading capacity but the spread is now lower than before the financial crisis.

Critics counter-argue that many investors have higher holdings of corporate bonds than before so there is a greater need for market making capacity. In particular there are worries about the rise in retail holdings of corporate bond mutual funds (driven by a search for higher yields). Large scale withdrawals from these funds could lead to selling of corporate bonds that would overwhelm market making capacity and possibly lead to a panic that the mutual funds couldn’t honour their stated net asset values.

For central banks, ensuring that there is always enough liquidity is a key part of ensuring financial stability and reducing the damage from financial crises and panics, which are likely always to be with us.

Peter Nowicki

Liquidity is key in the Resolution Plans that the Fed failed recently for a number of banks. The Fed wants an ongoing process to ensure that the liquidity assumption process is ingrained for the banks and not just a static test which once passed is ignored till the next submission. The process is one that needs new modeling techniques that are both quantitative as well as qualitative. The banks need to change their approach and should expect the Fed to be very challenging for those that just want to game the process. Culture change is necessary but most banks haven’t really done this. Should the banks consider selling assets in normal times to get smaller or deal with selling them in distressed conditions at substantial discounts.