The world’s most expensive power station project, a new nuclear reactor at Hinkley Point C in the UK, still hasn’t reached financial close, despite backing from the UK, French and Chinese governments. It might be best for the UK if it never does. The full story is told in my new book The Fall and Rise of Nuclear Power in Britain – A History which is published in March. An event to discuss the book will be held at the British Academy on the evening of 13 April, open to all (sign up here).

*

Background to the problem

Hinkley Point C (“HPC”) is meant to be the first new nuclear station to be built in the UK for twenty years. French nuclear giant EDF announced in 2008 that it intended to build a 3,200MW plant using the French-German designed European Pressurised-water Reactor (EPR), a Generation III design (meaning higher efficiency and safety). In 2013, at least two years behind the original schedule, the project cleared all planning hurdles and seemed ready to start. In 2014, the European Commission approved the UK government state aid support, after an initially frosty opinion. (The British government is promising that the British electricity customers will buy the power at a price that is more than double the current electricity price, indexed to inflation, for 35 years). In October 2015 the British and Chinese governments signed a statement on cooperation on civil nuclear energy at the time of President Xi Jinping’s state visit to the UK, reflecting the 33.5% of the project to be invested by state owned company China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN)

But the project has still not reached “final investment decision”, the point where EDF and its partner actually commit the funds and construction can start.

EDF is in financial difficulty

The main reason is that EDF is in financial difficulties, caused largely by tougher regulation in France and the onerous cost of refurbishing and upgrading the existing French nuclear stations. EDF’s latest group results in February 2016 showed the once mighty utility having high debt and negative cashflow. Reflecting this weakness, EDF cut the dividend from €1.25 to €1.1, something that companies are very reluctant to do. The French state, which owns 85% of EDF shares could do with the money but has taken the latest dividend in the form of new shares, a form of capital increase which very partially reverses the original privatisation.

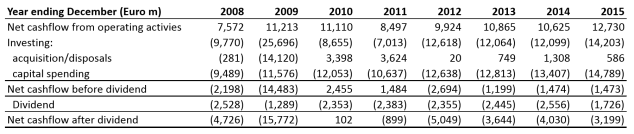

Here is EDF’s summary cashflow position (brackets indicate negative numbers).

EDF has had negative cashflow before paying its dividend for most of the years since 2008. The exceptional outflow in 2009 was for the acquisition of British Energy, which owns the UK’s more modern nuclear power stations. But the level of ordinary capital spending is worryingly high relative to net cashflow from operating activities. Once the dividend is deducted the company looks to be in a seriously cash negative position.

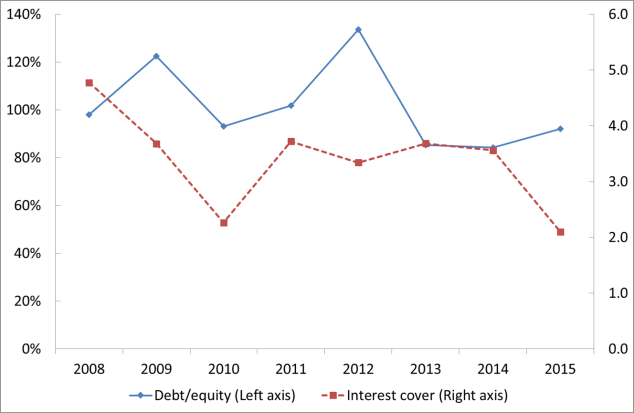

Another way of looking at the company is its leverage (or gearing). We can look at this on a stock basis (net debt to equity) or flow (operating profit over interest payments). Either way the company looks highly leveraged.

A utility with safe regulated returns can usually run with high leverage but EDF’s returns are under pressure and more of its market is being opened to competion Against that backdrop interest cover of less than three times looks low (note that 2015 profits were depressed by write-offs).

Investing in Hinkley Point C would be a huge and risky step for EDF

So EDF is already in a weak position and it faces large future capital spending costs in its domestic business. What would the investment in HPC look like in comparison? We assume here that EDF keeps its share of the project at 66.5%, though it hopes to sell some of that to other investors at some point in future. We assume that the base construction cost is the £16 billion (excluding £2 billion of costs already incurred *) that EDF announced in October 2015 (up from £14 billion a year earlier). We also use a high case of £22bn, which comes from the £24bn figure that the European Commission used in its state aid approval document, minus £2bn of money already spent. Of course the upper limit could be far higher than that. HPC is a European Pressurised-water Reactor (EPR). The two under construction in Europe, in Finland and France, are both running at about three times their original budgeted cost. But hopefully lessons have been learned from those and from the two EPRs under construction in China, which are much less over budget.

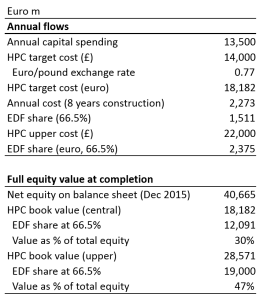

There are two ways we can judge the impact on EDF. First, I compare the annual cost of funding construction with the existing normal capital spending of EDF, using €13.5 billion as an average of the last four years (it’s likely to be higher than this in future). Second I look at the scale of the completed project compared with EDF’s existing total equity. In each case I look at the base cost case and the upper cost case.

This table shows the results.

My admittedly rough and ready calculations show that EDF’s share of the financing cost of HPC would be about €1.5 billion a year over eight years on the base case and €2.4 billion on the high cost case. In practice this funding will be off balance sheet, borrowed through a separate non-recourse vehicle. But that is a fair gauge of the economic impact on the EDF group. Perhaps just about manageable but it would put the group even further into negative net cashflow and place the future dividend payments in jeopardy.

If we look at the effect of a completed HPC project on the EDF balance sheet we see that its two thirds share of HPC would account for some 30% of the total equity of the group, or 47% if the project cost goes to the higher case. That shows the enormity of this project; it would be by far the largest asset on the EDF balance sheet. If it turns out to be very profitable it would a wonderful deal. But if it goes wrong it could destroy EDF’s financial credibility.

EDF won’t go bust because it is majority owned by the French government. But is the French state really prepared to underwrite this extraordinarily expensive project for the UK?

The shares have dropped by three quarters since the plan was first announced in 2008

Shareholders in EDF have lost a lot of confidence since the original plan to invest in Hinkley Point C in 2008. The shares have fallen by three quarters from their peak. The company’s market equity value is now about €20 billion.

The planned 66.5% stake in Hinkley Point would amount to €12 billion if it stuck to the target cost and €19 billion if costs reach the higher level. To put it with English understatement, the project would be somewhat material to the group’s financial position. In blunter words, going ahead with Hinkley would amount to betting the entire company.

Conclusion: Hoping the French pull the plug

It is now quite possibly in both the UK and France’s interests for HPC to be cancelled. That would save the UK electrictiy customer from paying a high price for power and save the French government and EDF from the alarming risk of the project going wrong.

But the UK government can’t cancel it without damaging its already tarnished reputation for policy consistency. It could scare off the other nuclear project consortia (backed by Japanese companies Hitachi and Toshiba) who are pushing ahead with what should be somewhat cheaper nuclear investments in the UK. These new reactors are essential for the UK to hit its carbon emission targets arising from the 2008 Climate Change Act.

It would also be a little embarrassing because the UK and China signed that statement of cooperation and the UK has been trying hard to be friends with China in recent years. But if HPC didn’t go ahead it would still leave the door open to the plan for a wholly Chinese nuclear station intended for Bradwell in Essex.

So we need the cancellation to come from France. Let’s hope they do the right thing.

(*) Yes, EDF has already spent £2 billion on this project, in the form of preliminary civil engineering works, design costs and a large team of people.

UPDATE

EDF’s Chief Financial Officer reported to have resigned because he believe proceeding with Hinkley Point C could jeopardise EDF’s financial position (7 March 2016)

Ian A. Crossley

Dear Prof Taylor

I have been carrying out correspondence with my local MP, Hugo Swire, about HPC, which I believe is a huge waste of resources that would be better spent of CCGT stations. He has been passing on my letters to Amber Rudd for response. Incidentally, have no links with the power generation industry or any NGO and I wrote to him as a concerned citizen. Mr Swire was very responsive, however, the DECC responses were what one might term “boiler plate”. I am interested in your analyses and views that EDF are likely to withdraw from the project. Analyses like yours are a very important way of balancing the “stacked” analyses from DECC.

Orderly retreat is difficult to accomplish, especially for politicians!

Yours truly, Ian A. Crossley, MIMechE, CEng

Simon Taylor

thanks. I don’t think I would say that EDF are “likely” to withdraw, it’s a political decision so I really can’t say how likely it is. I just think it would be best for us (and for them!).