Evidence from Nigeria shows that access to finance can help households reduce the impact of bad luck, reducing the fall in consumption that they suffer.

*

Yesterday I was part of a group discussing a draft research paper on the ethics of banking, prepared for Cambridge Judge Business School’s Centre for Compliance and Trust. I will send a copy of the final version of this excellent paper to the incoming MFin class. It argues that before we can talk about ethics and trust we need to ask, what is the social purpose of banking? Banks, unlike most businesses, can cause immense social damage because they periodically suffer crises, the costs of which hit innocent bystanders in the rest of the economy. For banks to be allowed to do risky things, they need to show they do something useful which more than compensates.

A basic human goal: consumption smoothing

One benefit of a well-functioning financial system (which includes more than just banks) is what economists call consumption smoothing. Economists assume that people care a lot about their consumption, meaning all the goods and services they use and enjoy. We also assume that people dislike volatility in their standard of living: in the face of inevitable “shocks” from the weather, economy, ill-health and so on, people would prefer a more steady flow of consumption to one that is volatile. Shocks – bad luck if you prefer – are inevitable in this risky world, and for low income households can be disastrous, tipping a family into extreme distress.

This desire for smoother consumption (which arises from risk aversion) seems well grounded in observations of human behaviour across many cultures, and gives rise to the need for insurance, which can be defined as paying to reduce the risk of unwanted outcomes. It can be done through formal insurance companies but in low income countries insurance is often done via marriage, inter-household support and precautionary savings.

Consumption smoothing also takes place over a person’s lifetime. A key challenge for all humans lucky enough to live to retirement age, is to provide an income for when they no longer earn. There are many possible solutions, of which having children is a traditional one that increasingly fails to work in higher income countries. Saving out of earned income into a pension fund is the solution for these countries. The risk being insured here is a very predictable one, namely that you will not be earning beyond a certain age but don’t want to see a collapse in your standard of living. So you smooth your consumption by saving while in the mid-life, relatively high income years and dissaving during your later years.

A lot of what is misleadingly called welfare is actually a form of consumption smoothing, managing the risks of ill-health, disability and economic shocks. Since private insurance markets don’t work very well in these areas, the insurance is commonly done through the state, which can both ensure everybody pays in to the system and provide a credible guarantee of payout when required.

Finance as a way of dealing with adversity

Access to finance also plays an important part in consumption smoothing, which is one of its most socially useful purposes. A new research paper from the IMF finds that access to finance reduces the volatility of household income in Nigeria quite considerably. Households with access to formal finance saw their consumption fall by 15 percentage points less, on average, than for households without access, when hit by shocks.

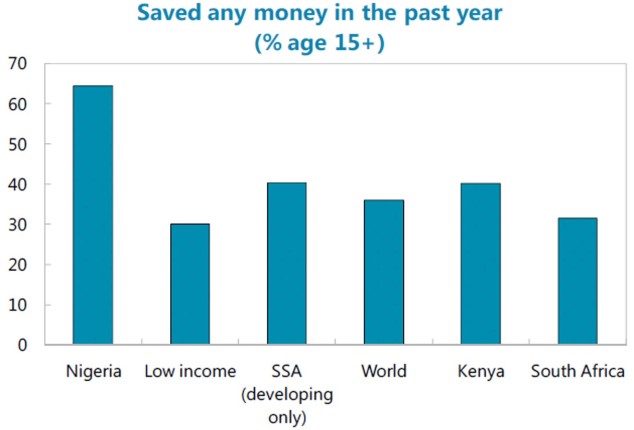

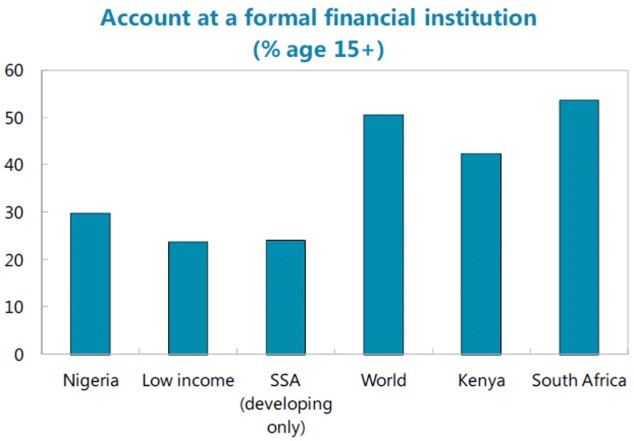

Nigeria has lower financial inclusion (access to financial services) than most countries in the world, though it is a little higher than the rest of developing Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The charts below show that although Nigerians lack access to bank accounts, far more of them save (65%) compared with the world as a whole (36%) or with low income countries (30%). The difference in Nigeria is saving through informal financial institutions called Rotating Savings and Credit Association (ROSCAs). A group of people (perhaps connected by clan, tribe or geography) save into the scheme and each cycle one person gets to take out a lump sum. These schemes offer a limited but valuable financial service to those outside the formal banking system.

The IMF research uses the Nigerian General Household Survey to measure the volatility of consumption when households suffer shocks. Those with access to finance suffer a fall in consumption 15 percentage points lower than those without access. But the effect is mainly because of those with informal access, via ROSCAs. It is the access to savings that helps, not access to credit, which is unavailable for most households. So ROSCAs appear to offer a way of saving combined with access to liquid funds when needed.

It would be better if more Nigerians had access to formal finance, even in a non-bank way. Other evidence cited in the paper shows that in Kenya, users of the mobile phone payments service M-Pesa suffer less from shocks because they have better access to remittances and other payments from relatives. A combination of accessible savings plus the ability to borrow to overcome temporary adversity would be best. Credit unions and cooperatives offer some of these services but a broader banking system would be better. The Central Bank of Nigeria hopes to reduce the rate of financial exclusion (those without formal or informal financial access) from 46% to 20% by 2020.

Note that ROSCAs and other community-based schemes can help insure against household-specific shocks (eg an accident that temporarily stops a person working) but not shocks that affect the whole region or economy such as drought, disease or economic recessions. For these only the state can provide insurance, using its ability to borrow across the generations, so each generation of people can insure through future generations.

Martyn

Why would broader access to the formal banking scheme be better? It would seem to me on the evidence you have presented here that it would improve the lives of poor people better if the informal sector was strengthened. Making them more reliant on the formal sector would make them more vulnerable, expose them to greater reliance on debt and crucially pass decision-making to exploitative elite institutions.

Simon Taylor

The IMF report gave no evidence that formal financial access was exploitative. I’m not sure what you mean by elite but banks need a mass customer base to succeed. There is nothing to stop informal financial institutions thriving if they offer a better service than banks (and credit unions continue to survive in the US for example). The line between informal and formal is not completely clear cut. Formal finance in the form of banks can mean a wider range of loans and the evidence of the report is that access can help households limit drops in consumption when their income falls, which is surely a good thing.