Central banks have balance sheets like other banks and in theory their liabilities can exceed their assets, meaning they are insolvent. But they can always create new money so they can settle their debts. So can they really go bust?

*

A bank (or any other company) is insolvent if its assets are less than its liabilities. It is illegal in many countries to trade while insolvent because you are commiting a type of fraud on anyone who owes you money, since you have no reason to think you will be able to pay them back. Nonetheless an organisation that is insolvent may be able to keep functioning if it can meet its daily cashflow needs.

The standard insolvency criterion I mentioned above applies to the stock of assets and liabilities – the balance sheet, which is defined at a point in time. What matters for day to day viability is the flow of income and expenditure. So a firm that has net liabilities (i.e. negative equity) might be able to keep going if it somehow has enough daily cashflows to pay for its daily costs. At some point, if the balance sheet figures have been correctly calculated, that ability will run out, but possibly not for some time.

Years ago a friend of mine worked for a development bank in a southern African nation. He was surprised to learn that it had negative capital yet it carried on running. This is not a situation anyone intended or that I would recommend but it shows that balance sheet insolvency isn’t necessarily the same as a functional ability to pay your costs.

The magic of central bank balance sheets

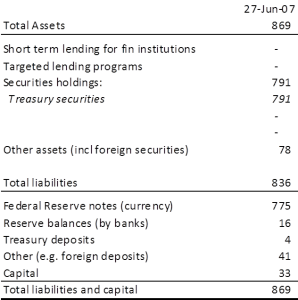

Central banks are an extreme type of company because they can create new liabilities at zero cost out of nowhere, so long as they have credibility with the rest of the banking system. Here’s the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve system in the “normal” days before quantitative easing (QE) as of 27 June 2007.

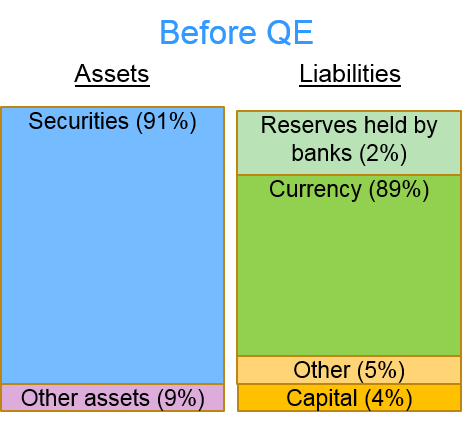

The Fed’s assets were almost all holdings of securities (all federal government bonds and bills, so zero credit risk). It financed these holdings mainly by issuing currency, which costs it very little (just printing and security costs). It had a small amount of reserve balances owing to the commercial banks which are members of the Federal Reserve system, which are used for settling claims between those banks, with the Fed acting as clearing house (the original function of central banks). Note that “capital” (which means equity) was a very small amount. No interest was paid on the banks’ reserves at that time.

The Fed had interest-bearing assets (securities) with non-interest-bearing liabilities. So even a small positive interest rate on the assets implies the Fed would be profitable, and potentially very profitable. Most of the Fed’s profits are passed to the Treasury, which is notionally its “owner”.

To make things simpler, here is the balance sheet in graphical form, somewhat simplified.

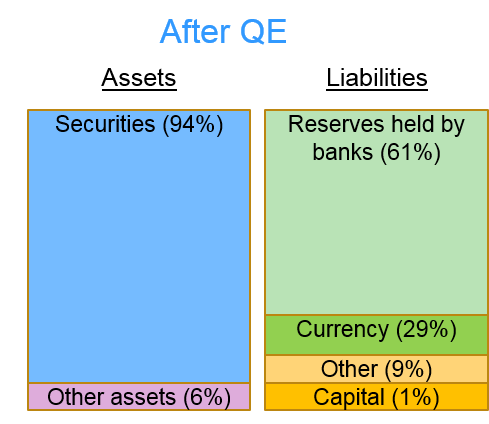

Things have changed a bit since. First, the Fed’s balance sheet structure has changed owing to QE. Now it still holds securities but they are financed in large part by a vastly larger reserves held by the commercial banks. This change is shown indicatively in this diagram (from the Fed’s balance sheet at 25 February 2015).

The second change is that the Fed now pays interest on those reserves held by the commercial banks. Indeed that is now a way in which monetary policy can be implemented, alongside the traditional open market operations, although we haven’t yet seen how this will work since interest rates haven’t been changed since December 2008.

Before QE, the Fed issued cost-free currency and used to buy interest bearing securities. Now it finances its securities holdings, most of which were bought in the market under the QE programmes (now ended) with interest-bearing reserves. And the interest rate it receives on many of those securities is fairly low. The spread between what the Fed earns and what it pays has gone down. It could in theory go to zero or even negative, meaning the Fed could be paying more for its liabilities than it receives on its assets, implying an annual loss. That is unlikely for some time to come, because interest rates are unlikely to rise quickly (as Chair Janet Yellen made clear recently).

But what about the solvency of the balance sheet? The Fed bought securities in the market at the market price (or just above it, to induce institutional owners to sell). Is has those securities sitting on its balance sheet at either acquisition cost or mark to market. What if interest rates rise in future and the value of those securities falls? Or what if the Fed sells them back to the market, reversing QE, and drives down the prices of federal securities in general by doing so? Either way the Fed might have to report a loss on its securities holdings.

Capital is there to absorb losses. But the Fed has a very narrow capital base. At 25 February its capital was just 1.3% of its total assets (or if you prefer the Fed was leveraged 77 times. This would be reckless in any other financial institution. It means just a 1.3% fall in its holdings of assets would wipe out all of its capital and make the Fed insolvent.

What if a central bank is insolvent?

It’s not clear that the Fed would immediately face any operating difficulties, even if its assets were less than its liabilities. Even if it has to pay net interest, it can do this in the form of adding to the reserves of the commercial banks directly i.e. by creating the interest from nothing. But that is not ideal and would likely inflame worries (previously groundless) that the Fed was taking risks with the stability of the monetary system.

The credibility of the Fed rests on its backing by the US government. It is unthinkable that the government would allow it to get into a position where it couldn’t operate normally or achieve is monetary policy goals. So there is an implicit backing from the Treasury, which could provide additional capital or some other form of temporary assistance, perhaps secured on future profits (once the Fed eventually gets back to “normal” operations).

But the risk in that scenario is that politicians sieze the chance to impose additional conditions or restrictions on the Fed’s behaviour. There is a long standing distrust of central banks in US political history and there are repeated calls from some Republican members of Congress to audit the Fed more (it already is audited in detail). Any such intervention might damage the long term independence and credibility of the Fed.

Many central banks face a similar situation to the Fed. They have assets (often also US government securities) which are paying very low interest rates and liabiilties which may pay a higher rate. They therefore face a dilemma. They can raise returns on their assets by shifting towards higher risk and higher return securities. Or they can risk going bust and hoping that their governments will bail them out without threatening their credibility.

One might argue that a central bank that is insolvent will inevitably lose some credibility, as it hardly looks like good financial management. But it is a real possibility during these times of unusual monetary policy and very low interest rates.

nick0123N

America is nearly $ 20T in the red as a 3 generations in the red so Insolvent is not the word. It is that capacity to Print beside the Chinese that Help To Stay otherwise few countries will follow …

Philip Moore

Another really nicely explained post. Too much material on central banking glosses over the subject of interest payments and subsequent ramifications. Good stuff!

shahid saleem

A well explained and thought provoking article. Fed or any central bank shouldn’t start something just to keep music running.