I recently visited Mumbai for the first time in over 10 years. A lot had changed and India may be poised to take over from China as the fastest growing major economy.

*

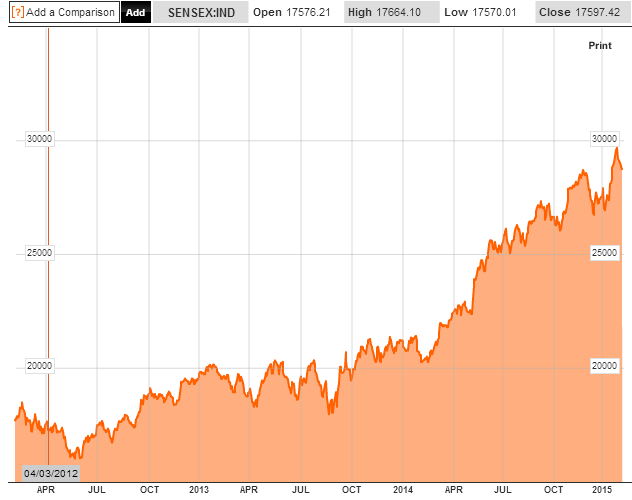

Mumbai is the commercial, financial and film-making capital of India. I visited the city several times from 2003-2005 to set up a new research centre for JPMorgan, initially with 20 analysts and now with some 150. I went back for a short trip recently to promote the Cambridge MFin. It’s an interesting time to take stock of India’s economic prospects. There is a lot of optimism about the future because of the relatively new Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The highly respected governor of the Reserve Bank of India, Raghuram Rajan, is gradually convincing people that inflation will be kept under control. The stock market has boomed in anticipation of future GDP acceleration.(see chart below).

A history of disappointing growth

India matters to non-Indians because it one of the world’s largest economies and it contains most of the world’s poorest people. It is also the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide, after China and the USA. In the increasingly fractious world of Asian politics it is one of the three major players, alongside China and Japan.

India’s economic potential remains vast but it has repeatedly disappointed in the past. For decades after independence in 1947, India followed highly interventionist economic policies with a great deal of regulation and protection from foreign trade. These policies, which were recommended by western economists, including it must be said from Cambridge, led to very low GDP growth, barely above the level of population growth. Development economists in the 1950s and 1960s were obsessed with the macroeconomics of savings, arguing that developing economies needed extra savings to allow them to boost investment. There is something in this view but the policies badly neglected the supply side of the economy. The economy cannot flourish if there are multiple barriers to getting anything done. You need spend only a few minutes in Mumbai to see that Indians do not lack for entrepreneurial flair. But this spirit was held back for years by the “licence Raj” in which free enterprise was strangled. The result was that per capita GDP grew at only 1.3% between 1950 and 1990, a dismal result misleadingly called the “Hindu rate of growth”. The low growth had nothing to do with Hinduism and everything to do with bad economic policies followed by secular, western educated prime ministers. Economies in east and south-east Asia did dramatically better during the same period, though China, India’s main rival, also grew relatively slowly until it swapped Maoism for capitalism in the 1980s.

Growth picked up markedly in the 1990s after the first wave of liberalisation under prime minister Narasimha Rao and finance minister Manmohan Singh. (Dr Singh did his undergraduate economics degree at Cambridge and his doctorate at Oxford.) As is so often the case, it took a crisis to bring about reform. India faced a balance of payments problem in the late 1980s. By the end of 1990 the country’s foreign exchange reserves were down to the equivalent of three weeks of imports. A healthy level would be three months’ worth. Close to default on its obligation, the government accepted an IMF bailout, secured on 67 tonnes of Indian gold, some of which was airlifted to the Bank of England.

India had previously managed to remain economically as well as politically independent so it was embarrassing to have to take IMF funds but the shock effect was productive. The liberalisation reforms were opposed by many vested interests and by those who saw them as being imposed by the IMF. The IMF has often had to bear the brunt of criticism for forcing countries to introduce economic policies which are not only good for the country but which the domestic government wanted to effect but could only do so under the cover of IMF loan conditions. Indian GDP growth per head accelerated to about 7% over the next two decades, a rate that started to make inroads into poverty.

But the momentum of liberalisation faded as the crisis receded in memory and GDP growth had decelerated. The last five years are widely seen as having achieved very little in economic policy. The widespread sense of hope over the government elected in May 2104 reflects frustration that India had seemingly gone backwards. It’s a little early to know whether Modi’s cautious but determined attempts to improve India as a place to do business and to attract more foreign investment will be enough to push economic growth back up again but there is a lot of optimism in India.

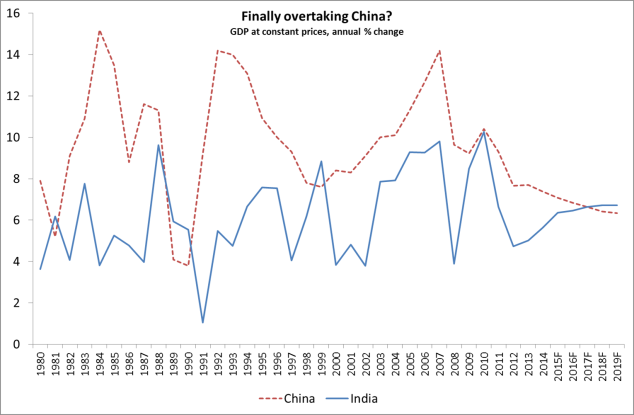

In 2014 India is estimated to have grown at 5.8% and China at 7.4%. In January 2015, the latest IMF forecasts predicted GDP growth in India would exceed that of China at some point in 2016. This is of course partly because China is now forecast to grow at 6.5%, down from its former 10% compound rate. India is forecast to match that in 2016 and then accelerate beyond it, if it fully achieves the potential of the Modi reforms, backed up by a credible monetary policy from Prof. Rajan (see chart below).

Economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to reduce poverty. In many indicators of poverty and quality of life, India lags behind not just China, which is a richer country, but Bangladesh, which is not. Nobel prize winning economist Amartya Sen (formerly the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge) pointed out four years ago that India could and should do far more on poverty, female literacy and health even with its current resources, without having to wait for faster economic growth. China has brought some half a billion people out of poverty. It would be a wonderful thing if India could do the same.

Aside from economic reform, the main theme of Modi’s first year as prime minister has been foreign policy. Most strikingly, President Obama attended India’s Republic Day celebration of independence, the day before I arrived in Mumbai. The papers were naturally full of this remarkable visit. India has for decades proudly asserted a non-aligned policy, not wanting to get caught up with either side during the Cold War and refusing to be labelled by essentially European measures (if Russia can be regarded as for the most part European). Obama’s visit was in stark contrast to the refusal by the USA to grant Modi a visa in 2005, when he was Chief Minister of Gujarat. For the US to get closer to India makes good sense. India is the world’s largest democracy and is a natural ally of the US in its goal of neutralising China’s rise. If India can achieve a decisive increase in GDP growth it will provide a democratic counter example to the successful rise of authoritarian China.

India versus China?

It was striking to me, on an admittedly short trip, to witness the enthusiasm and optimism in Mumbai. On frequent visits to China I have experienced something similar but it is tainted by a sense of anxiety about how China’s rapid economic development will play out. India’s history is far more integrated into the rest of the world than that of China. Mainly because of geography, India has closer links with the rest of the Eurasian continent, including the linguistic roots of European languages. Despite the burden of European and especially British imperialism, India seems more at ease with its past and less in a hurry to prove to the world that it is important. China often seems torn between enormous pride at the country’s economic achievement and insecurity about its global status.

From an old fashioned but still relevant European balance of power view, it is probably good for the stability of Asia that India and China are, very broadly, matched for size and power. China is clearly ahead on GDP but India has far more soft power and a lot more friends, something that Modi is building on. It remains to be seen whether India can match China for economic growth. In the mid-21st century India’s population will surpass that of China. If it catches up on GDP per head too – which is quite a tall order – then it will become the world’s largest economy. Discussions about the future of Asia have in recent years been dominated by western – specifically American – worries about the rise of China and the risk that its already troubled relationship with its neighbours spills into conflict, into which the US would be dragged. India, which has until recently been punching below its weight (according to The Hindu newspaper), is the other vitally important part of the story of more than half the human race.The current century will almost certainly be Asian but not necessarily only Chinese.

UPDATE

A comment by the author of the BRICS concept, Jim O’Neil, who is optimistic about India’s future

Dan

Would love to read your thoughts on the Indian banks…http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-01-19/burger-flipping-wages-for-india-bank-chiefs-dent-competitiveness