The biggest topic in the global economy remains the oil price. It’s notoriously difficult to forecast commodity prices but how can we make sense of what would push the price up or down? A basic demand and supply framework gets us quite a long way

*

A market consists of demand, supply and some mechanism for setting prices. The crude oil market is one of the most global and most important. How can the price fall by more than 50% in six months, without anybody forecasting it? And how can we analyse what the price might be in future? I can’t offer a prediction but here are some ways to think about it.

Demand and supply can be captured in a simple diagram that sums all the market participants’ wilingness to buy (demand) or sell (supply) at each price. A market is in balance (“equilibrium”) if demand and supply are equal. The price that matches demand and supply is the market price.

So far, so obvious. This framework becomes more useful if we distinguish short and long run demand and supply. The concepts of short and long run go back to the Cambridge economist Alfred Marshall, who was one of the most important economists of his time (the last nineteenth and early twentieth century). His textbook Principles of Economics, written in 1890, was the standard one in British universities and was the one that Keynes studied.

Short and long run responses to price: elasticity

The short run is not a specific chronological period. It means a period when agents can make few adjustments to their costs or procedures. So in the short run I have a particular car and house heating system which commit me to a particular choice of fuel and energy efficiency. If the price of oil or gas rises I will be limited in my scope for changing behaviour so I may not buy much less than before, even though I’m unhappy about the higher price. This means that the short run price elasticity (the sensitivity of demand to a change in price) is quite low. This is equivalent to a steeply sloped demand curve.

But in the long run I can buy a more fuel efficient car (and cars become more efficienty partly to reflect increasing demand for fuel efficiency but also because governments set increasingly tough efficiency targets). And I can buy a house with a different type of central heating system or get the house insulated (these are admittedly less easy to do, which is why buildings are the most intractable area of energy efficiency improvement).

My price elasticity is much higher in the long run because I can make more changes than in the short run. The demand curves is therefor less steeply sloped in the long run. The same is true of supply, which captures the behaviour of producers.

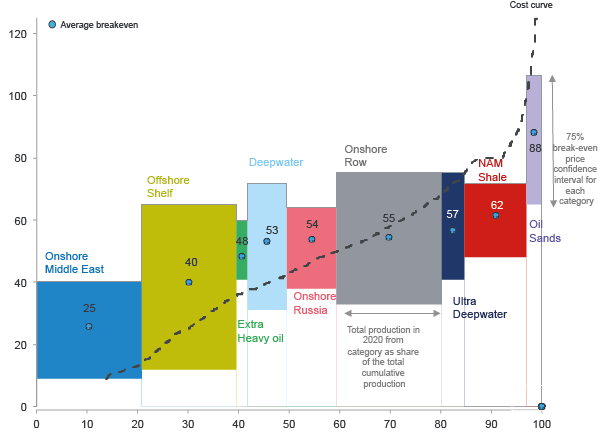

Consider the effect of a fall in oil prices on suppliers. In the short run, though it hurts profits, producers will rationally keep producing until the cash income from production is less than marginal cost of production. Even if the business is making an accounting profit loss it is better off covering at least variable costs, rather than shutting down altogether. The variable costs of different types of oil vary enormously from about a few dollars a barrel in Saudi Arabia to $60 or more in US unconvential (“shale”) oil (see chart below).

So the price elasticity of supply is quite low in the short term. But the producers will make other decisions that affect long term supply. We are hearing daily about the cancellation of new investments into oil exploration and production that are not likely to be profitable unless prices rise a lot. The oil companies have to make decisions over decades to come so they can’t scrap all new investment. But they have to revise down their long term price expectations to some extent.

The oil market supply reaction is still in the short run

Putting all this together means there is a short term market price equilibrium which reflects the big rise in supply in the last year, mainly from the US, Libya and Iraq, combined with a somewhat lower than previously expected level of demand, because the world economy is growing less fast than expected (but probably still faster than it was in 2013 and 2014). That price is currently about $50 for Brent crude. There are lots of oil producers, especially in the US, which are covering their variable costs at that price but not their fixed costs. So they are making an accounting loss and will not be investing in any new production unless they are confident the price will rise again.

The lower cost producers such as the onshore Middle East are still profitable at the current price, though they are suffering a big loss of income compared with what they made a year ago. They are not going to change production and they will probably keep investing, since even the newer fields in the Middle East are still profitable at current levels.

Offshore investment, especially deep water, is much more questionable an investment at current prices. Some projects are already committed (a lot of investment has already taken place and the companies are reluctant to write it off, even though economic logic says these costs are largely sunk so they should be irrelevant to future decisions). But many others that would have proceeded at higher oil prices will now be postponed.

Those decisions amount to the long term supply reponse. The volume of oil that is profitable (including covering fixed costs) at $50 is likely to be lower than the current amount being produced. If new investment falls and the older wells gradually run out (especially in US shale where the depletion rate is much faster than in conventional oil) then global supply will fall.

Demand will keep rising so long as rising incomes (“the new global middle class”) lead to rising energy demand, especially for cars and trucks. If governments are smart enough to remove subsidies and even push up carbon-based taxes then the price to the consumer will not fall that much. But underlying global demand is likely to keep rising for many years to come.

Lots of current production may not be profitable at current prices

At some future price, higher than at present, long run demand and long run supply will be balanced and the oil market will find a new equilibrium. I don’t know what that is but if you had all the data on demand and supply you could at least come up with a sensible estimate. For the supply side, here is an interesting chart from a new IMF working paper, estimating the break even price for different types of oil supply. It shows the price of oil on the vertical axis and the supply, ranked from lowest cost to highest along the horizontal axis with an estimated break even price for each category. So oil sands, the type of oil found particularly in Canada, have a breakeven price of $88. These supplies will eventually dwindle, with no investment in new capacity, if prices remain close to current levels.

If this chart is correct then around half of current oil supply is not profitable at $50/barrel. So if the short run lasts a year or so then the price can remain about $50. But it cannot stay at that level indefinitely because the long run supply curve of oil doesn’t intersect the long run demand curve at that price. The price at which it does intersect is very important but hard to estimate.

UPDATE

Some long term perspective on commodity cycles from Carmen Reinhart. The current commodity price bust is very much in line with history it seems.

An IMF model of oil price forecasts using purely statistical analysis.

Abhinav Charan

Simon – fascinating article!

Two questions:

1. You explained that the market is currently in the ‘short run’ mindset. But who or what decides that the market needs to move to the ‘long run’ mode? Does it always take black swan events like these ($50 Brent) to cause the paradigm shifts we are witnessing?

2. In the current price scenario, Saudi Arabia/OPEC can produce cheaply whilst American shale producers can’t cut the mustard. How does that impact swing production? Historically Saudi Arabia has been the swing producer. But since the Middle East will keep pumping oil at this price now, will that make the US the swing producer of the future?

Simon Taylor

The short and long run are concepts. The market is constantly adjusting, with new projects being planned, started up and completed. The idea of the short run is that market participants have not yet had time to adjust their response because some factors of production (labour and capital) are fixed. Over time, labour can be moved (ie fired) and eventually capital can be re-deployed, though much of its irrecoverably gone.

A black swan event is one that couldn’t have been predicted because it lay outside the conceptual framework of the people doing the planning. The recent fall is not a Black Swan event. Oil prices collapsed in the mid-1980s and they will do again one day, because that is how commodity markets work.

My analysis largely applied to a competitive market. Saudi Arabia has, at times, controlled part of global supply in order to influence prices. Saudi, unlike most of the rest of the Middle East, has very large reserves of low cost oil that will last for many decades. It therefore has a long term perspective on supply. Other OPEC producers will have exhausted much of their reserves in the next few decades and want to maximise revenue while they can. That clash of interests is one reason why OPEC has never been that good at fixing the oil price. The other is that much of the new oil supply is coming from outside OPEC. There need not be a swing producer, which is a rather thankless task. The price of oil in a competitive market will be set by the marginal producer (the one which is just able to make a profit). That could indeed be the US. But that doesn’t mean the US has any power over the oil market, just that US shale producers’ decisions will have an impact on the oil price.

VS

Greeting!

In competitive market, the oil prices should equal marginal costs. Unlike the monopoly price regime, the monopolist can pick a price wherever above marginal costs and then restrict production to ensure that supply does not exceed demand. The unconventional producer in the US is a real games changer. Under the current market, the marginal cost of US shale oil would become a ceiling for global oil prices, whereas the costs of marginal conventional oilfields in OPEC and Russia would set a floor. At the low oil price, the shale producer need to stop the production and can resume whenever the oil price picks up to the certain level. Some said the oil price will have w-shape movement. If so, do you think the supply-demand reaction can sustainably develop from the short run to long run?

Simon Taylor

Current oil prices (which are somewhat higher than when I wrote the blog) are consistent with some shale production continuing but not with high levels of new investment in additional shale capacity. So that’s why longer term prices are likely to rise. But there could be quite a long lag. So long as the current shale producers are covering their cash costs they will keep producing. We’ve heard a lot about cuts in oil investment but very little about oil production cuts. But eventually the existing shale oil wells will run down (in fact they deplete quite quickly compared with conventional oil and gas) and production will start to fall. Unless demand has risen even more, prices should then rise, or even earlier in anticipation. But this process can be erratic and volatile. Textbook charts showing a smooth adjustment from one equilibrium to another are only a device to help understanding. In reality we are constantly adjusting and there is no reason to expect a smooth price adjustment.

Samina Akhtar

Greetings!

Just want to ask that in most of the markets supply is more elastic in the long run than in the short run, why is it so?

Why producers supply more than the increase in the price of the particular product in the long run?

Simon Taylor

In the short run, some of the factors of production are fixed. In the long run they are all flexible. So producers are more flexible in the long run to respond to price changes, either up or down. If prices rise for example, a producer might want to produce more, to make higher profits, but be constrained by current capacity, which is based on previous capital spending. Over time the producer can invest more, raise capacity and so produce more than in the short run. Similar considerations apply in the case of a price fall, though it’s not symmetric. Capital invested in existing capacity cannot be easily withdrawn and reallocated to other uses even in the long term so it may be economic to keep producing a similar amount, even when prices fall, until the equipment wears out or is no longer worth refurbishing. So eventually a fall in price will be followed by a fall in output but possibly not for a long time. By contrast a rise in price will be followed a rise in output as quickly as the new investment can be carried out (assuming the suppliers believe the price rise is going to last).

Samina Akhtar

Respected Sir thank you so much for this elaborated reply.

God Bless You.

Humble regards,

Brilliant Fane

how can an economy in the short run and long run enjoy consumption beyond its production possibility curve

Simon Taylor

A country, like a person, can consume beyond its income if it can borrow. This is possible in the short run but not in the long run, because the debt will have to be repaid. Nobody will lend to a country that seems unable to one day generate income in excess of consumption sufficient to repay the debt. But plenty have managed to borrow in the short run, though sometimes they later defaulted. Normally borrowing would fund investment, not consumption, which should lead to higher future income, out of which the loan can be repaid. Borrowing to fund consumption only makes sense if there is a temporary fall in income, perhaps because of a recession or natural disaster.

Patience

I am looking at the market and how it has shown that so far demand is elastic as relative to the inelastic belief of demand and supply for oil.

can it be said that while demand is elastic supply is inelastic, using the current oil price.

Rk

What happens both in the short-run and long run if oil producers can come together to restrict the output of oil.

Simon Taylor

We know from history that oil producers can sometimes effectively restrict supply and thereby push up short term prices (the Opec oil “shock” of 1973-74 is the best example). But the challenge in doing this is both the incentives (countries differ in their view of the optimal oil price) and enforcement (some countries cheat, to the frustration of Saudi Arabia which takes the main burden of cutting supply). So producer restrictions happen less often than might seem desirable from their point of view.

Interested Reader

Hello. Is it possible to estimate demand curves with any certainty? It seems to be to be just as important as the supply curve, but I assume it is very difficult to do? Thank you

Simon Taylor

Certainty is not available. But demand curves can be estimated with high enough accuracy when the data are available. There are many cases in public policy (e.g. transport planning) where economists have accurately estimated the future demand for new road or metro services. Oil demand is one of the most important demand curves in the economy and both private and public organisations estimate demand. The volatility in prices is usually more owing to supply surprises and shocks to overall demand (from recessions or booms). It’s possible to estimate the underlying demand for the next few years with some success, excluding these external surprises. Longer term demand is more uncertain because of technological innovations that affect the demand for all energy and for oil versus other energy sources (e.g. how quickly will electric cars go mainstream).

Jan Sand

Hello, is it possible to have a supply curve that intersects the demand curve twice? Since many oil prouducing countries need to keep up their income one could imagine a segment of the supply curve for which price times volume is constant. This would happen for low prices and cause the curve to twist to the right.

Simon Taylor

Theoretically perhaps but it’s unlikely in practice. There is no doubt that in a weak demand context, commodity producing nations can end up producing a lot more to maintain their income but in doing so they cause prices to fall further. This is the problem of collective action. If the producers could successfully collude they could push prices up, at least for a while. We have recently seen an unprecedented agreement between Saudi Arabia and Russia to manage production. This presumably reflects desparation, especially in Russia, where the government budget is in tatters and there are likely to be severe cuts in spending, at least after the forthcoming elections. Whether this agreement will have any lasting effect remains to be seen. Short term prices did rise after the deal.

Nic DellaCioppa

Everything that I have read about North American Shale with respect to low cost Middle Eastern oil production tells me the US government needs to be involved in the equation. Oil price is still a strategic resource that must remain in balance to prevent disastrous consequences to the US economy. Right now many of the North American shale producers are going bankrupt. What is to prevent Saudi Arabia or even China from scooping up the associated resource at bargain basement prices? The US government needs to step in and acquire (and possibly going forward put some regulation on domestic production) these assets so they don’t fall into the hands of other governments that don’t have the best interest of the US consumer in mind. The other risk is that all the positive gains made in renewable energy sources could be erased as well if global oil prices stay too low for an extended period of time. The best policy right now would be for the US government to provide some oversight over the production of US shale, trying to only kick up production when oil prices rise above $60 a barrel. While keeping the resources in check when oil market price dips below $50 a barrel.

Matt

Nice blog post. There is something that still puzzles me about this analysis. You claim that in the short run both demand and supply are inelastic. But if this was the case, any short-run change in supply and demand would move prices by a huge amount, and actual production would never change (imagine a diagram where both demand and supply are very steep. Equilibrium production is constant). However the data seem to refute at least in part this hypothesis: production and usage (consumption) move somewhat on a month to month basis, and prices do not move 50% from month to month. Hence a little bit of short-run elasticity (either on the demand side, or on the supply side, or both) must necessarily be present.

Simon Taylor

Yes there is some elasticity. For the extreme case you suggest, the electricity market is a good example. Very inflexible demand and supply does indeed produce dramatic 1000x price changes. This happened in the California electricity crisis of 2000 and 2001. Dramatic rises in prices produced windfall profits for producers such as Enron, later found guilty of manipulating the market.

Inderpal

how change in oil prices changes elasticity of demand?

Simon Taylor

Price elasticity of demand for any good or service is the sensitivity of demand to a change in price. It’s defined as the percentage change in demand over the percentage change in price. The elasticity itself depends on the time horizon (it’s typically higher in the long run because it’s easier to make changes than in the short run).

OB

What happens both in the short-run and long-run if oil producers can come together to restrict the output of oil.

Simon Taylor

OPEC has tried to do this for 50 years, with some mixed success but oil prices have still varied a lot. Now it makes no difference, long term demand for oil is in decline and the price will trend downwards, even if it fluctuates along the way, as we gradually decarbonise the world economy. Eventually oil will be irrelevant to the world economy.