A New York Times article recently reported data from Rosenblatt Securities showing that the percentage of total US stock trading done “off-exchange” has risen from about 15% in 2008 to over 35% in 2013 and occasionally as high as 40%. What does this mean?

Conventionally, stocks (shares) are traded on an exchange, which is an organised facility that brings together buyers and sellers for mutually advantageous trade. Originally exchanges were physical places where buyers met sellers. The greater the number of each that the exchange attracted, the more liquid and valuable the market was. Exchanges existed for many tradeable commodities. Many British towns have a corn exchange, which was once used by farmers to buy and sell cereal crops. Cambridge’s Corn Exchange is now the city’s largest performance venue, though it retains the original grand Victorian interior (and accompanying poor acoustics unfortunately).

Most exchanges today are virtual – all trading is electronic and there is no physical trading space. The New York Stock Exchange is one of the few remaining where you can actually see traders (known on the NYSE as specialists) actually walking around and doing deals with each other. This vanished in Europe many years ago. Today’s London Stock Exchange is just an office block.

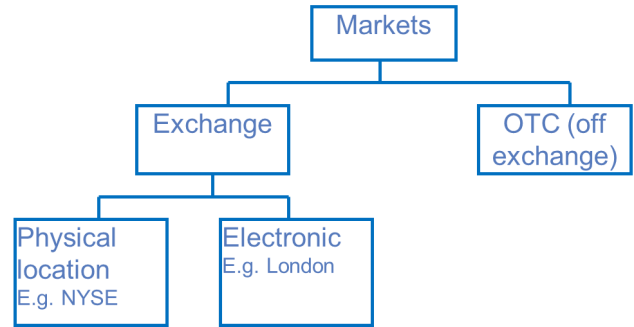

Not all trading of financial instruments is done on exchanges. Most bonds, FX and derivatives are traded directly between the banks with no third party exchange taking part. These over the counter (OTC) markets are highly organised and sophisticated but lack a central clearing house or counterparty, something that regulators believe makes them more vulnerable to credit risk. The different types of markets for financial instruments are summarised in this diagram.

The value of exchanges

Exchanges historically had two functions. The first was to achieve a liquid and effective market by bringing together buyers and sellers. The second was to restrict access to members who could be trusted to honour their deals. An effective market uses orders – stylised instructions for buying and selling such as “buy JPM at the market” or “sell IBM limit 30”. These orders, which are now usually matched by computers for smaller volumes, allow trade to take place quickly with a minimal risk of error. It would slow things down unacceptably if each time you traded you had to check the creditworthiness and credibility of your counterparty (the other member you were trading with). Restricting membership to people who were believed to be trustworthy and solvent made this checking unnecessary. Occasionally somebody might still default or abscond without delivering the shares they promised to sell but this cost could be met through mutual insurance through the exchange. London Stock Exchange members were required to take exams and to be of “good character”. Of course, like any club, an exchange can become a means of keeping out the riff raff, with the risk of becoming inbred and closed to new talent.

The private benefits of exchanges are clear – each trader gets the best price available at any moment in time by having access to the largest volume of potential counterparties. There is also a public benefit because the exchange publishes prices that show the going rate – the market price – of each security. Outsider users of this data, including companies, investors, regulators and governments know that these market prices are the best guide to the current market value of the securities, because they emerge from a large and liquid market.

Anything which diverts trade to other markets or fragments trades therefore risks reducing the credibility of the market prices. If the exchange accounts for only a portion of trading in a security then it might not be showing a fully representative price. This is what has happened with the move to trading off-exchange.

Off-exchange trading

The plunge in IT costs in the last twenty years has allowed competitors to exchanges to spring up. These at first took the form of relatively simple order matching mechanisms for out of hours trading, which didn’t compete too much with the exchanges. But in the last decade the competition has become very real in the form of dark pools and internalisation of flow by the largest investment banks.

A dark pool is an electronic mechanism for bringing buyers and sellers together, away from the exchange. It’s “dark” because everything is anonymous and traders needn’t disclose their orders, even long after they’ve been completed. This is different from exchanges, which publish trade data, with some lag in timing to allow larger orders to be fulfilled safely. Dark pools deny public information on trading prices and volumes.

Internalisation is where a bank matches buy and sell orders entirely through its own book, using market making to smooth out differences between buy and sell volume at any moment in time. This can only be done effectively if carried out on a large scale so only the largest trading houses, known as ‘flow monsters’, are in a position to do this. The banks achieve two things. First, they get a lot of liquidity which can be useful in reducing the costs of hedging other trades. For example access to large amounts of cash equities flow can help cut the cost of hedging equities derivatives trading.

Second, the bank gets an insight into the direction of flows. In other words, it can see which way the market is moving and trade on its own account accordingly to maximise profits. This is not insider trading, since it doesn’t depend on specific information affecting a stock. But having the knowledge of short term trading flows in aggregate is undoubtedly a profitable piece of information. Even if trading on the bank’s own book (proprietary trading) is banned by the Volcker Rule, the bank can still make money in its market making function, where it is permitted to tilt its position long or short to allow it to maximise profit consistent with providing liquidity to the market.

Internalisation, like dark pools, reduces the information available to public traders in equities. Confusingly, some dark pools are operated by exchanges, as part of the competition for customer business, though they tend to prefer the less dramatic term “non-displayed” market.

Challenges for regulators

Stock exchanges were once their own regulators. This wasn’t too unreasonable because the exchanges were owned by their members (they were mutual organisations) and had a strong interest in protecting the rules of conduct and their reputation. This was not the whole story, since insider trading used to be legal and it was therefore an enormous advantage to be a member of an exchange and part of the insider crowd. Outsiders had to rely on the advice of their brokers and hope they were indeed insiders who could pass on accurate tips to their customers.

Stock exchanges are now typically normal, for-profit companies and regulation is done by government entities such as the Securities and Exchanges Commission in the US. Regulators face something of a dilemma when considering what to do about off-exchange trading.

If customers wish to use new trading opportunities, either because they’re cheaper or because they offer anonymity, then it is not the job of the regulator to stop them. The problem is that the new facilities mainly benefit the largest investors, who like the fact that they can transact the larger, more difficult to trade volumes of stock, without the pressure of stock exchange rules saying they must disclose the trade prices.

But this means smaller investors may be left to trade in the conventional exchange market, which is less reflective of true demand and supply. The market price as shown in the exchange is no longer necessarily the true market price. And liquidity on the exchange is reduced by the diversion of flows off exchange.

In essence this is a conflict between some private interests and the wider public interest in the value of what economists call price discovery. Markets do lots of useful things but providing accurate prices is one of the most helpful. The market price of equities is one of the most important economic numbers in the economy, as it tells us the overall price of equity risk. If the price shown by exchanges is no longer accurate then there is a loss of information to a wide range of financial decision makers.

At a deeper level there is an interesting conundrum here. Markets become most efficient when they grow larger, because they are subject to economies of scale or more accurately increasing returns to scale. There was a brief period when several online second hand markets competed with each other for success but eventually eBay won out by achieving dominant scale. Once a single market operator has achieved leading scale it’s hard for competitors to survive. It’s not just the cost advantages but the network benefit. If you want to buy some particular 1970s comic books you will look where the largest number of sellers are likely to be and they will likewise seek the place where there is the largest volume of buyers. Once eBay established itself as this place, it became very hard for anybody else to compete.

A similar logic has led to widespread M&A and concentration among stock exchanges. Most of the continental European market trading is now dominated by Deutsche Boerse and Euronext, the latter being owned by the New York Stock Exchange. At one point a few years ago it looked as if the German and UK markets would become integrated under one ownership. A single European stock exchange seemed possible, if regulators allowed it.

But the tendency towards monopoly risks leading to typical monopoly behaviour – higher prices and lousy service, because of the very lack of competition. Monopolies that are inherently due to cost or technical reasons (so called “natural monopolies” such as water and electricity distribution networks) are usually regulated for this reason, through direct price and conduct rules. Monopolies that are thought to be amenable to competition can be broken up and exposed to new entrants and market forces, as happened with the break up of the US telephony monopoly in 1984, though that industry has now re-concentrated back to a de facto duopoly.

So a vigilant regulator (two words not so often seen in the same sentence) needs to be mindful of the genuine benefits of scale that push a market close to monopoly while being open to technical changes, such as the fall in IT costs, that allow competition. At the current state of play the regulators are clearly nervous about the scale of off exchange trading and are considering requiring greater trade price disclosure that would limit the loss of information. But it’s a fast changing industry and there is no clear rule as to what the regulators should do.

Samir Prakash

Simon – fascinating stuff. Questions:

1. You identify a regulatory challenge created by off-exchange trading: “the new facilities mainly benefit the largest investors…” Although I don’t know the details, this hints at competitive distortion, against smaller players, with the potential for market failure. My question is: Is it not possible to quantify the harm that may result from the reduction of information available publicly and thus the weakening of price discovery? I’d imagine this is an area of research with competing theories/models. In particular, if the possible public harm of off-exchange trading outweighs the private benefits then would that not be grounds for regulatory intervention? (Perhaps this is a legal question and perhaps the relevant law has not kept up with market developments.)

2. You discuss later the causal link between market size and market efficiency. I’m not clear but are you suggesting that the provision of a market (say, by a normal, for-profit concern) can or should, therefore, be regarded as a service that is a “natural monopoly”? In much industrial regulation today, an underlying principle or doctrine is to encourage competition, in all its forms, as an intervention-minimal way to achieve the greatest net benefits for consumers. But when it appears clear that competition will not naturally achieve the desired conditions – or eliminate unacceptable harm, then intervene in a “heavier” form (to prohibit unacceptable practices or level the playing field somehow). If market provision is not naturally amenable to competition, then why the regulatory dilemma – fundamentally – about intervening in off-exchange trading to protect consumers, protect smaller players, and secure the greatest net benefit for the greatest number of market participants?

Simon Taylor

1. A situation where larger customers benefit at the expense of smaller is quite common in business and not a market failure in the economics sense of the term. Measuring the costs and benefits is very hard, particularly when the industry is changing so fast. Regulators are on weak grounds in blocking clear benefits arising from free market forces based on an unquantified cost to others.

2. A market has some of the characteristics of a natural monopoly, yes, because of the network externality effect – the increasing returns to scale. But even where there are non-natural monopoly features in an industry, there is a good argument for letting competition erode them, though it takes time. Microsoft’s de facto monopoly in PC operating systems has eventually become irrelevant because PCs are now only a small fraction of the total computing market – competition based on innovation has gradually disciplined Microsoft. An earlier intervention to break the monopoly would have saved us all years of crashes and long start up times but it might have blocked or slowed the innovation that gives us smartphones. So it’s hard for a regulator to know what is the right policy.

paul

Simon, do you believe that capital can act like a black hole at times?

Simon Taylor

I’m afraid I don’t understand the question.