It is fifty years since the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. Many people have said that this period marked the most important historical event of the twentieth century, namely that the USA and the USSR did NOT go to nuclear war. In the Cuban missile crisis they came closer than ever before or since. As the publicity for a film about the crisis (Thirteen Days) put it, you’ll never know how close we came. President Kennedy put the odds of war at 50/50 at one point. The world gambled – and won. If events had gone the other way, this blog would not exist and nor would most of the northern hemisphere.

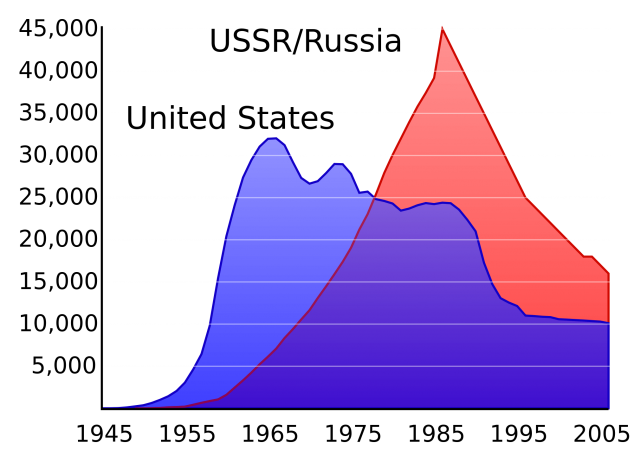

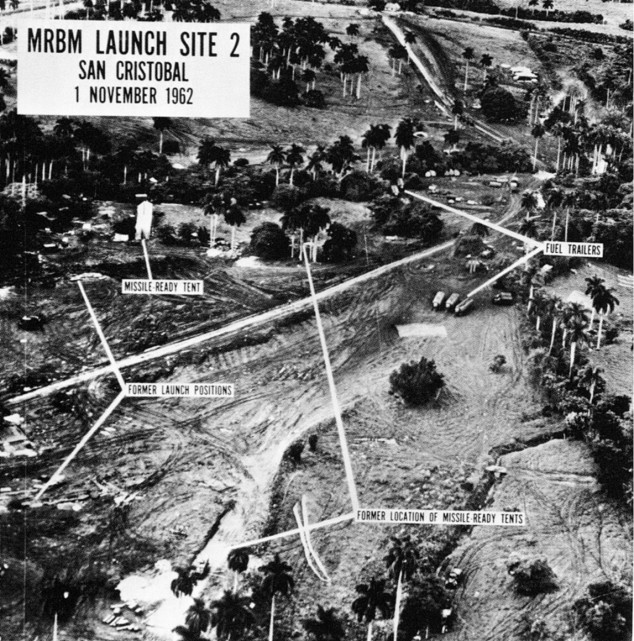

The facts are still coming into focus, as archive documents continue to be revealed (for example the transcript of a conversation between the Cuban president and a senior Soviet official has only just been published). But the main events have been known for some time. On October 14 1962 an American U-2 reconnaissance plane photographed Soviet SS-4 medium range nuclear missiles in Cuba. The Soviets in private and in public denied their existence. The American president, John F. Kennedy, on 22 October announced on nationwide TV that the US would start a naval blockade of Cuba, and demanded the withdrawal of the missiles. The Soviets initially refused and the two countries went to the brink of nuclear war. Although the US had a massive superiority in nuclear missiles, the USSR had more than enough warheads to destroy the USA. A private deal was done between Kennedy and Russian premier Nikita Kruschev on 27 October (only revealed decades later) in which the US withdrew largely obsolete nuclear missiles from Italy and Turkey in exchange for the withdrawal of the Soviet missiles from Cuba. Kruschev was fired two years later, in large part for the recklessness that led to Soviet humiliation. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas in November 1963.

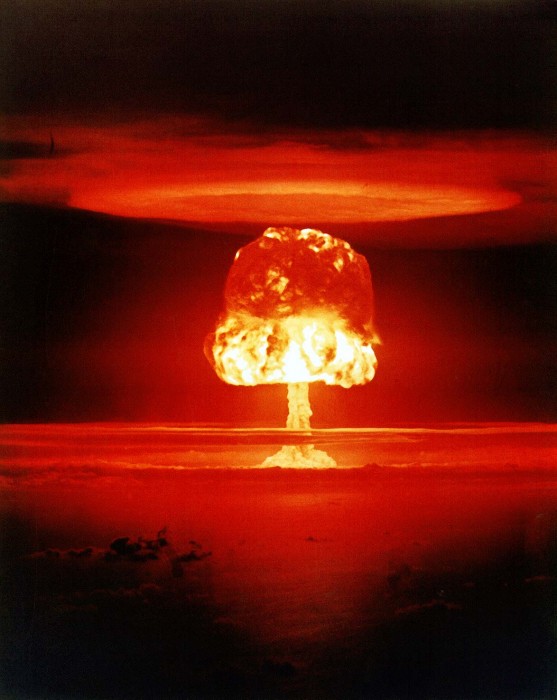

There have been at least two other times when there was nearly nuclear war between the two superpowers, both owing to accident and misunderstanding (see below). Cuba was the only time (so far) that the countries nearly went to war over a matter of actual military conflict. (The US went on nuclear alert during the 1973 Middle East war, mainly to show it would not tolerate Israel losing). Had war broken out, both countries would have launched hundreds of nuclear missiles at each other and their allies. Most of North America and Europe would have lain in radioactive ruins. The deaths would have numbered hundreds of millions and European-based civilisation would have been finished. On some theories there might have been environmental damage that would have threatened all life on earth. A well researched scenario in which the human race continues but there is little left of the northern hemisphere is available here – it is not happy reading.

So human history nearly stopped – or at least nearly went down a very different path – in 1962. What was learned from this?

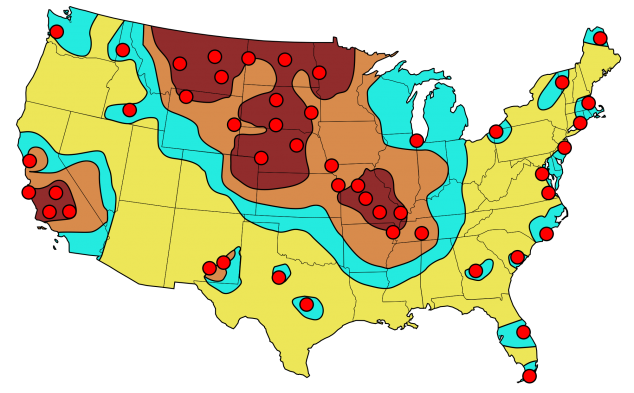

Nuclear war is exceptional in two respects. First, its destructive scope, sufficient to kill the great majority of the human race. Second, in its ballistic missile form, its extremely fast execution. There is a chilling moment (one of many) in Thirteen Days when Kevin Costner, playing an aide to President Kennedy, is talking about the allocation of White House staff to different fallout shelters. He then confides to a colleague that the message is purely for morale. In reality there would be no time to get to the shelters (not that they would have helped much). The missiles could reach Washington DC in less than fifteen minutes. By the time the President knew they were on their way it would be too late to do anything, let alone formulate a clear plan of action.

This hair trigger quality (submarine launched missiles could reach the US or USSR even faster) gave rise to the doctrine of survivability and second strikes. If the US could survive (in a strictly military sense) a first strike and still threaten credibly to retaliate against the USSR then the Soviets would logically and rationally not try to make a first strike. With symmetrical logic, the USA would not try either. So emerged an uneasy equilibrium known unofficially as mutual assured destruction (MAD). In the rather clever and entertaining film War Games (with a young Matthew Broderick, later to star in the utterly brilliant Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, undoubtedly the most popular film in my household), a computer learns that the only winning move with global thermonuclear war is not to play. In other words, GTW is a negative sum game.

The need for timely communication between the superpowers led to the installation of the hot line, a direct phone channel from Washington DC to Moscow that would allow misunderstandings to be dealt with quickly, as well as for negotiations and threats to be expressed.

Deliberate nuclear war became completely irrational. But there are two documented incidents when it nearly happened owing to error. The early 1980s were a time of heightened tensions between the USA, with President Ronald Reagan offering some bellicose anti-Soviet rhetoric (*) against an increasingly economically weak and paranoid USSR. The USA has also introduced the exceptionally accurate Pershing II intermediate range missiles in West Germany. From a Soviet point of view, the only way to counter missiles that could accurately destroy their missile silos in six minutes or less, was to strike first. This inherent instability ought to have made the Americans cautious but it seems that it never occurred to them that the Soviets might genuinely think that the USA would attack. But the combination of the Russian experience of Hitler’s surprise attack in 1941 and the Cold War suspicions of the new Soviet Premier Andropov, formerly head of the KGB, meant that an American sneak attack seemed highly possible.

The first incident was almost comical in its absurdity. In September 1983 a Soviet missile early warning system indicated that a single US intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) had been launched. The system operator, Stanislav Petrov, knew this was very unlikely – the US would launch either launch hundreds of missiles or none. Shortly afterwards the system indicated that four further missiles had been launched. Petrov correctly interpreted this also as an error.

The Soviet early warning system was designed to “see” the flash of an ICBM launch over the horizon but was confused by an unusual pattern of sunlight on high altitude clouds. The level of anxiety in the Soviet leadership was very high, and relations with the US especially strained following the shooting down three weeks earlier by a Soviet fighter jet of Korean Airlines flight 007, which had strayed into Soviet airspace, with the death of all 269 passengers and crew. Had Petrov not shown initiative and judgement, his report might have encouraged a nervous Moscow to launch a nuclear strike on the US in false anticipation of a US attack on them.

When the incident became public in the 1990s, Petrov was quite correctly labelled the man who saved the world (though he was apparently reprimanded by the Soviet military for inaccurately completing the paperwork on the incident). A world which can get so close to a disaster averted only by one man’s willingness to challenge the technology is a crazy and frightening one.

The second incident followed close behind. In November 1983 a Nato exercise called Able Archer that simulated a full transition to war made Soviet military analysts fear that the West was using the war game as a cover for a real attack. The Soviets noticed, but could not decode, an unusual flurry of communications between the US and UK, which seemed consistent with preparations for war. In fact they concerned the US invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada in October 1983, to the great annoyance of the British, who were not consulted. (The head of state of Grenada is Queen Elizabeth II.)

The US had not the slightest intention of attacking the USSR, but it seems clear from later declassified files that the Soviet high command really feared the US was out to destroy them. The rational thing to do in that case is to attack first. Able Archer ended and the Soviets eventually relaxed. When the Americans realised how close they had accidentally come to provoking a Soviet strike, and after Ronald Reagan had been moved and depressed by an American TV documentary about nuclear war (The Day After, which had a profound effect on public opinion), he became convinced that the US and USSR must find a way to put the threat of nuclear war behind them. The superpower tension began to ease, strategic arms deals were done and of course in 1991 the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Russia inherited the nuclear weapons.

It remains the case that the only true existential threat to the USA is the fact that several thousand Russian nuclear warheads are targetted on it. No sane person would press the button to fire them but the risk of accident or unintended consequences remains. Many former leading Cold War figures now argue for full nuclear disarmament. But not only is there little progress at the superpower level (and the UK is currently not helping here) but the risk of regional proliferation is greater than ever.

Robert S. McNamara, Kennedy’s Secretary of State for Defense at the time of the Cuban crisis and through several years of the Vietnam war (and later head of the World Bank), made a brilliant documentary film in 2003 called The Fog of War. In the film he reflected on Vietnam and on Cuba. One of his lessons was: “The indefinite combinations of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will lead to the destruction of nations.”

*

(*) In a speech to the British House of Commons on 8 March 1992, President Reagan predicted that “… freedom and democracy will leave Marxism and Leninism on the ash heap of history.” The phrase was chosen by his speechwriter to echo similar words used by Leon Trotsky at the time of the Bolshevik/Menshevik split that led to the October 1917 revolution. There is evidence that the Soviet leadership really thought Reagan intended to bring this ash heap about. Reagan was, as for so much of his life, just acting.

Anthony Smith

Anyone remember that German chap who landed a Cessna in Red Square ? So much for defence, eh ?

Simon Taylor

And remember Neun und Neunzig Luftballoons? Doesn’t seem quite so far fetched now.

Anthony Smith

That was a horribly mimsy song. Germans should stick to prog .And think, if the Americans had done Cuba in, we wouldn’t have Strictly. Sorry, slightly off topic about the End Of The World