I last visited South Africa in 1987, during the apartheid period. Since at that time there was a cultural and economic boycott of the country, I should explain to alarmed friends that I was there because I was working for two years in the Central Bank of Lesotho, a small former British protectorate that is entirely surrounded by South Africa and largely economically dependent on it. It was impossible, other than by flying, to leave Lesotho without crossing into SA, which in any case my job occasionally required. Returning this July was a fascinating and somewhat emotional experience. A lot has changed for me and more importantly for the country in the last quarter century. The trip, to promote the Cambridge University MBA and MFin programmes, was also a chance to meet alumni, some old friends and make a couple of new ones, courtesy of my colleague, MBA Director Jochen Runde, who grew up in Johannesburg.

Apartheid

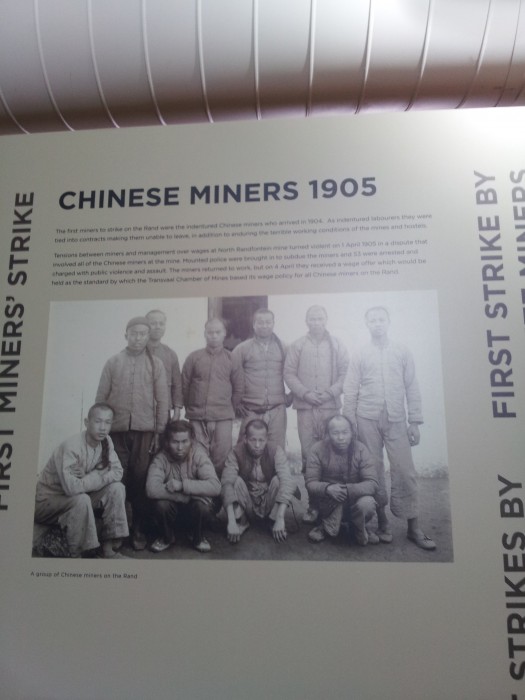

There is plenty of competition for evil regimes but apartheid must have a strong claim to be top of the list. Rooted in the economic policies of the colonial British, the full horror of “separate development” as it was mendaciously termed, began in 1948. (To get some historical context, recall that Rosa Parks refused to sit in the blacks-only part of a bus in Alabama, USA in 1955 and most of the European colonies lacked democracy at that time). The economic logic is simple: South Africa’s main wealth lies in its deposits of gold and other minerals, which require large numbers of low cost miners. In the early twentieth century these miners were a mixture of white and black, but their limited numbers gave them union bargaining power so the mines brought in Chinese indentured workers, who were both subject to racist abuse and badly exploited. The Museum Africa in central Jo’burg tells how there were around 100,000 Chinese at one stage but they were eventually sent home to appease white miners. But the search for cheap labour led to the use of more black labour instead.

http://www.gauteng.net/attractions/entry/museum_africa/

The British found ingeniously unpleasant ways to “encourage” blacks to work in the mines, including the hut tax, a tax on every dwelling payable in cash, which could only be earned through paid labour. But the policies of the Union of South Africa, created when Britain granted independence in 1910, went much further, intending to build a racially segregated society. By 1948 black people were forced to live in designated areas, were not free to move without permission, must work only in certain jobs, could not marry white people and were denied any political power and the majority of normal human rights.

The genius of the system was to create supposedly independent countries in which blacks lived so that technically South Africa was an entirely white nation, which owned the great majority of the land. These artificial black “homelands” were loosely based on tribal names and regions, the apartheid regime learning the lesson from the British (and other European colonists) of divide and rule. The four allegedly independent homeland states – Transkei, Bophutatswana, Venda and Ciskei – were never recognised by any foreign country, though Israel allowed some to set up embassies there and Taiwan had some economic relations with them.

Lesotho

All of this was quite clear from the UK, there was no need to visit South Africa to see it in operation. Lesotho was on the frontier of this system. It was for a while a political base for the ANC (African National Congress), the main opposition group against apartheid, founded in 1912, and which started to use violence after the Sharpeville massacre of 1960, including against civilians, and was then banned (Nelson Mandela was officially taken off the US terrorism list only in 2008). Teaching at the National University of Lesotho at Roma, I came across several black students who spoke superb, barely accented English. The reason was that they had grown up in Sweden, which supported the ANC and allowed leaders’ children to grow up safely far away from the main ANC base in Zambia. Eventually the South African government tired of Lesotho’s safe harbour status for the ANC and fomented a military coup in 1986 by closing the border, leading to the expulsion of the ANC and anybody suspected of supporting them. Others were simply killed by South African special forces.

By the mid-1980s the regime was becoming increasingly violent, there were several states of emergency and the economy was deteriorating under the pressure of international sanctions and low commodity prices. The turning point was the refusal of Citibank and other American banks to roll over short term loans. Lest this seem heroic, these banks and many other western companies, had been bankrolling and profiting from the apartheid regime for decades. They only pulled out because of consumer pressure in the US and UK and the increasing credit risk of the regime. This does make the point though that going for the money is the way to kill these evil regimes.

Current difficulties in context

There was a strong sense that eventually apartheid would collapse but I was one of many who were pessimistic about a peaceful transition to democracy. The savagery of the regime, the bitterness of many blacks (and whites), the difficulty of including the vast majority of a disenfranchised population and the risk of economic disaster made it a near-miracle that there was a peaceful transition. This owes a huge amount to Nelson Mandela, a man who is in a class of its own when it comes to leadership. But the remarkable generosity of spirit of the whole ANC leadership and of blacks more generally is something to celebrate when listening to today’s pessimists.

For we have only to look at the recent shootings of workers in the platinum and gold mines to see how bad things are in this highly divided nation. Economic inequality is still very high, unemployment is around 36%, but far higher among young blacks, and South Africa is a de facto one party state under the ANC. A series of blogs by Acemoglu and Robinson, accompanying their book Why Nations Fail, examine the prospects. Some of the people I spoke with in South Africa fear a populist future in which the more radical elements of the ANC take over, nationalise the mines (a popular policy for the miners and their families who wonder what the end of Apartheid has changed here) and drive out foreign investors. Acemoglu and Robinson suggest, by contrast, that South Africa may become more like Colombia or more generally a Newly Latinamericanised Country (NLC). By this they mean a highly unequal country in which an elite controls power and wealth, discouraging or blocking economic development that would help the majority.

The ANC chose in 1994 to abandon the more radical content of the Freedom Charter of 1955 (which includes: “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people; The mineral wealth beneath the soil, the Banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole; All other industry and trade shall be controlled to assist the wellbeing of the people”). They opted instead for a mixed economy to reassure the skilled white workers and foreign investors that South Africa would not make the same mistakes as so many other African countries, and in particular Zimbabwe, the troubled neighbour to the north, a constant reminder of what a tyrannical leadership can inflict on a people. This mixed economy policy has worked in many respects but has not meant much for the mass of poor black people, who are therefore open to the more radical and confiscatory policies as urged by Julius Malema, recently fired as head of the ANC’s Youth League and who has emerged as a figure of hope to some and fear to others.

The enormous potential

And yet, the potential for South Africa remains so great. It is beautiful, has a superb climate (with the low winter night time temperatures meaning it is free of tropical diseases), some excellent infrastructure (though not in the townships) and a lot of well educated people who speak English well. It is in the European time zone and has plenty of space. It is a potential California of Africa. When at JPMorgan, we considered South Africa as a location for a new global research centre, but chose India because of its much larger pool of highly educated people. I believe some European bank outsourcing is done in South Africa, which has a sophisticated financial system. Meeting staff at some of the banks was a source of great inspiration. Around the table were people of every skin colour, enthusiastic, positive and impressive. I’m often rather gloomy about banks in the UK and US (they have done such a terrible job in recent years) and it was wonderful to leave a bank feeling so uplifted.

(On the matter of skin colour, the official Apartheid classification of white, coloured (mixed-race), black and Asian was always absurd. Race is a largely social construction, not biological. It is a sometimes amusing feature of the US, with its own deeply troubled history of racial segregation in the southern states, which looked a lot like Apartheid South Africa, that a “white” person may turn out to have one or more “black” ancestors or vice versa. I once sat at the conference table in the board room of the Central Bank of Lesotho for a meeting to initiate a structural adjustment loan. Present were people from the Bank, Treasury, IMF and World Bank. The Central Bank had about one hundred employees, 96 Basotho – people from Lesotho – and four expatriates, which included one Swedish governor, one Bangladeshi general manager, a Pakistani IMF adviser and me. Also present were people from Nigeria, Jamaica, Italy and Kenya. Basotho, proud of their status as being from a single nation, not tribe, are nonetheless quite varied in appearance. So, around the table was a rainbow of hues from very pale (the Swede, but with me not far behind) to very dark (the Nigerian) and every shade in between. The Italian was darker than some Africans. Any third party, on being told that a few miles away over the border they classify people into four skin colours, would have laughed.)

Downtown Johannesburg

Johannesburg’s centre was hollowed out in the earlier post-Apartheid years but is showing signs or revival. It is a lot more prosperous and lively than the city of Detroit when I visited it some years ago to meet a client. Recent research emphasises the importance of culture and the arts in urban regeneration. Artists and cultural entrepreneurs move into cheap, depressed areas and then attract the sort of skilled workers who like such neighbours, contributing to what in the UK we call gentrification. Perversely this eventually pushes up property values too high for most of the artists, who have to move. Downtown Manhattan and much of east London are now too expensive for any but the commercially successful artists to stay. But they did their job. MFin alum Rael Cline showed me a fledgling example in central Johannesburg of the same thing, a mixed artists studio, cafe, bookshop, exhibition space and shops. On a sunny day (it’s nearly always sunny in the Jo’burg winter) it was very appealing.

Perhaps it’s Jochen’s enthusiasm for art but we saw several great galleries in town. Here is one, rather empty but it was the winter.

It’s also refreshing to see shops that you don’t see in the increasingly identical British high streets. I like this one, with it’s international reach (Ougadougou is the capital of Burkina Faso by the way).

Leave a Reply