London is permanently in the news in Britain. But a number of recent stories get to the heart of what London is and should be, the subject of increasing disagreement among Londoners themselves.

First we have the imminent Olympics, a £9 billion extravaganza that is both the largest logistical exercise in the UK in peacetime and a source of great annoyance to many Londoners, who are being advised, in effect, to not leave home during the games to avoid over-loading the public transport system. Second, we have a sequence of scandals in the City of London, the financial centre of the UK. With the damage from the financial crisis of 2007-09 still far from repaired, we have had the fixing of LIBOR by Barclays and now the revelation of money laundering (in Mexico) by HSBC, until then the only British bank that appeared solvent, competent and principled. And then a few days ago we had a Bruce Springsteen concert in Hyde Park at which the sound was switched off in the middle of an historic duet with Sir Paul McCartney. Bruce was unimpressed, as were the thousands of ticket holders, but many other Londoners are fed up with the noise of outdoor events.

I was born just outside London but at the age of three moved to rural Lincolnshire. I spent the rest of my childhood trying to get out again. Lincolnshire has some of the finest towns and villages in the whole country (particularly the town of Stamford, where my parents still live) but it is not a very exciting place to be a teenager. I was happiest on our regular visits to London, where I had several relatives. My mother was born in County Cork, in Ireland, but her family, seeking like generations of Irish before them to escape the miserable economic conditions of that once and now again blighted country, moved to London. My grandfather got a job in one of the Irish construction companies. The family arrived just in time for the second world war and the Blitz, the Luftwaffe’s bombing of major British cities in what turned out to be a futile, even counterproductive attempt to defeat the UK. Life during the Blitz was very dangerous but from a child’s point of view quite exciting. My mother had two older brothers. One was killed in the war. The other one, too young to fight, played on bombsites where he picked up interesting things. One of these things was an unexploded incendiary bomb. Being a curious child who wanted to understand how it worked, he took it home and cut it in half with a hacksaw at which point it did what it was designed to do and set fire to the house. The fire brigade, who were really quite busy already, were not impressed when they heard the cause of the fire. But my Uncle Tom went on to a highly successful career as an electronics engineer, mostly in Canada. These days he would probably have been put in some sort of institution for delinquents and his curiosity either stifled or diverted into crime. My mother’s younger brother, Noel, carried on the family tradition of construction work but upgraded himself to interior decoration, culminating in a job to paint the Music Room at Buckingham Palace.

I can only assume that even the royals don’t pay their decorators much because Noel gave up being a painter and became a taxi driver. This requires the passing of a very stiff memory test called the “Knowledge”, which dates back to 1865. Each driver must memorise 320 “runs”, routes across London that require the naming of every key landmark and street name (25,000 of them) within six miles of Charing Cross. It takes around three years to master the Knowledge, which is done chiefly by tracking the routes repeatedly on a scooter, a common sight in London.

The Knowledge is why London taxi drivers, with all their faults in terms of sometimes talking too much and sharing their often rather extreme views, do at least know where they’re going, unlike their counterparts in New York.

London and debt

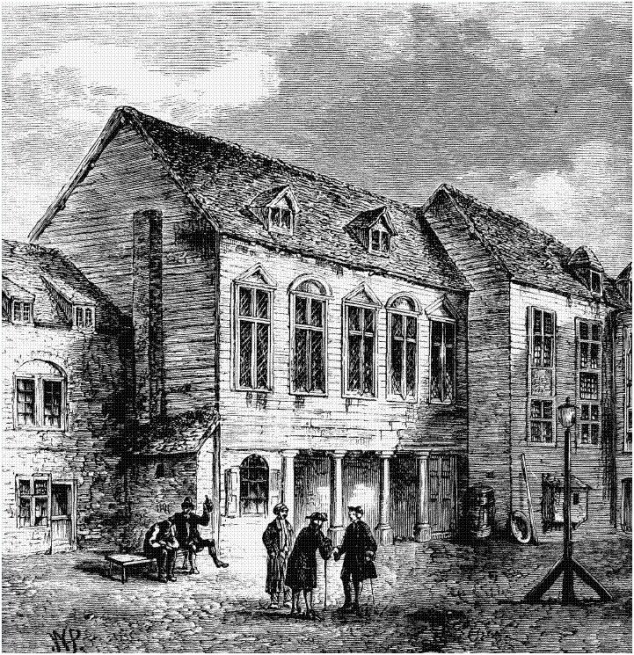

AN Wilson’s wonderful short history of London notes the irony that much of London’s success as a financial centre arose from a policy of embracing public debt, with the Bank of England founded to make a very profitable of business of managing it, yet private debt was heavily frowned on. In 1719, not long after the Bank was founded in 1689, around 60,000 people were in prison for failing to pay their debts. In London, some 300 people died of hunger in the debtor’s prison at Marshalsea (p. 46). This prison, run privately like all of Britain’s prisons at that time, according to Wikipedia “looked like an Oxbridge college and functioned as an extortion racket”. If you had money you could live quite well, even drink at a bar. If you didn’t, you starved to death.

Going into debtor’s prison was both dangerous and socially disastrous. Charles Dickens, whose stories chronicle the life of the poor in nineteenth century London, gave a vivid description of the social shame accompanying failure to pay ones debts, based on the experience of watching his own father imprisoned at Marshalsea, in his novel Little Dorrit. Dickens is still a hugely popular writer, though perhaps more for the film, TV and theatre versions of his books than for the books themselves. Some of them are quite long, which is an obstacle in today’s busy times. (He wrote his stories in episodic form for newspapers – they were the soaps of their day). If you’ve never read any Dickens, I’d recommend starting with the relatively short A Tale of Two Cities, which is set in London and Paris at the time of the French Revolution and the subsequent Terror. It’s perhaps a little sensationalist about the facts of the Revolution, which captivated, excited and terrified Londoners as they read of French aristocrats being beheaded (pioneered in London with the execution of Charles I in 1649 by the way). But it’s a great story, with one of the most wonderful beginnings of any book:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way– in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

It also has a famous last line:

“It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

Both beginning and ending featured in the film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn, which also includes references to Moby Dick (and you thought it was just a Hollywood action picture).

You can read or download A Tale of Two Cities free from various places such as Project Gutenberg or Google Books. (Star Trek II you’ll have to pay for).

Dickens was a master of character portraits that still move readers today, particularly on the subject of poverty and misfortune. George Orwell, as outstanding a British non-fiction writer as Dickens was of fiction, wrote a sympathetic essay Dickens and his portrayal of poverty and injustice. Orwell observed that Dickens thought that if only people would be kinder to each other then much unhappiness could be avoided. Orwell thought this was naive, and that Dickens failed to see that private property was the root of the problem. Orwell was perhaps naive in his own way, seeking a form of British socialism that would combine liberty with justice and avoid the tyranny of Soviet communism. He didn’t know that the second great communist experiment was about to begin, in China, and that it would decisively show that government planning and the abolition of private property lead to tyranny and mass murder.

Meanwhile London is once again a city of debtors, both among the general public and the state itself. It is also a city of enormous economic inequality, though the poor are less wretched than in Dickens’ day. The rich are increasingly foreign, as London has become the one true global city to which all billionaires and oligarchs come, to live, invest, sue each other or put their children into school. This influx keeps the city alive and stops it becoming a charming museum like Rome or Paris. But it makes ordinary Londoners whether it is still their city.

Leave a Reply