Even for people who’ve lived their whole lives in the UK, the Scottish independence debate is a bit confusing and perplexing. For those from abroad I know it’s quite bizarre. Here’s some background to a period which might lead to the break up of the United Kingdom.

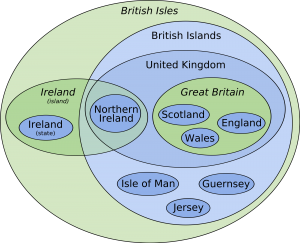

First some nomenclature. The United Kingdom consists of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Great Britain refers only to England, Scotland and Wales and is nothing to do with greatness in the sense of superiority, just to the larger of the two islands that were originally known as Pretannia then Britannia from before the Roman period. The history of Northern Ireland is so complex and controversial that I’ll say no more about it here. Wikipedia has a great diagram, which serves to emphasise the difficulty of just getting the names right.

Scotland was an independent sovereign nation state, quite separate from England (which conquered Wales in 1282). It was joined to England in 1603 when King James VI of Scotland became king of England too, owing to the dead Queen Elizabeth having no children. He became King James I of England but the two nations, as opposed to the monarchies, remained separate. Only in 1707 did they become a single country, the Kingdom of Great Britain, when a more or less bankrupt Scotland merged with England and scrapped its parliament in Edinburgh. Many Scots were unhappy with this arrangement, on which they were not consulted (nor were the English masses for that matter, in that pre-democratic age).

The Scottish parliament was revived in 1998 together with a degree of self-government for Scotland. A minority of Scots have, for many years, wanted full independence and the goal of partial devolution was to head off any secessionist pressure by appealing to the majority who just wanted not to be governed from London. But the electoral success over the last ten years of the Scottish National Party, culminating in its winning of a majority of seats in the election of 2010, means the SNP’s long standing policy of a referendum on full independence is now going to happen, probably in 2014.

Support for full independence is, according to opinion polls, in the range of 30-40%. But a much larger proportion of Scots might vote for devolution just short of independence. And the SNP may use the threat of secession from the UK to extract concessions from the Westminster parliament, in the way that Quebec has done in federal Canada and various regions of Spain have done.

But there are differences from the Canadian situation. In particular, a lot of English might be quite pleased if the Scots left, so long as the national debt is fairly divided and other financial matters are resolved. Scotland, being a poorer and markedly more unhealthy part of the UK, takes up a disproportionate share of public spending and generates a less than proportionate GDP. So Scotland leaving could be an investment banker’s dream, a spin off that enhances the value of the remaining core. But it depends how much of the North Sea Oil tax goes with Scotland, something that depends a lot on how you draw the Scottish/English coastal water boundary.

Now I’m not sure what the situation is in Canada, other than to say that quite a few Canadians, especially those in the western provinces, would be equally happy to see the back of the troublesome French-speakers in the East. But Canada is a federal country; the UK is not. The four constituent parts (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) all elect members of the Westminster (London) parliament. But England, unlike the other three parts, has no separate assembly of its own. So Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish MPs get to vote on laws that affect only the English but English MPs are excluded from voting on matters that affect only Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

So far this hasn’t caused any practical concerns, though it was irksome to some English people that there were so many Scots in the last British (Labour) government. Any further devolution for Scotland would inevitably raise the question, why should Scotland still elect full MPs to the Westminster parliament? But trying to find an intermediate solution (eg they don’t vote on matters that concern only England) would be very difficult and likely to inflame further the separatist instincts of Scots and English.

I don’t think Scottish independence is high up most English people’s list of concerns or interests. It’s most unlikely that it would change much practically, since Scotland would remain economically very much tied to the rest of the UK for the foreseeable future. Ireland, independent since 1922, still does the bulk of its trade with the UK (which helps explain why the UK helped in the Irish debt bail out, despite not being a member of the Euro).

But it’s not at all out of the question that the UK in its current form, has only a few years left. And if Scotland leaves, will the Welsh want to go too? Or will England itself demand independence?

Samir Prakash

Simon – Thanks for the explainer. Two question: How do you believe the national debt would be divided among the constituent parts of the UK if they decide to separate? What are the main other financial matters that would require resolution?

Samir

Simon Taylor

The national debt would be divided either in proportion to share of population or of GDP, the latter being lower because Scotland is lower income than the UK as a whole. There are other financial liabilities though, especially unfunded pensions for the public sector. I’m not sure what part of these are already devolved to Scotland but I suspect there are some that are not. Then there are the assets of the state balance sheet, including idiosyncratic ones like the Faslane Trident nuclear submarine base. These things can be done, as they were in the break up of the Soviet Union and in the “divorce” of Czechoslovakia. But they will take time and could be very controversial.

Alan MacBeth

You say Scotland is poorer than UK. This is just your opinion. Note that the Financial Times newspaper of London says that an independent Scotland will be better off per person than the rest of the UK. See their edition of 2nd Feb 2014.

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/5b5ec2ca-8a67-11e3-ba54-00144feab7de.html#slide1

But many people in Scotland will be voting Yes for what we see as a more important issue – fairness and equality. With the gap between the rich and poor growing in the UK (4th worst wealth distribution in the Western World) – many Scots will be voting Yes to permanently get rid of right-wing Conservative governments and their right-wing policies that we don’t vote for. Currently Scotland has 59 MPs – only ONE is a Conservative – but he gets to impose his austerity cuts on the poor of Scotland. This issue may not be on the BBC news or mainstream newspapers – but it is dominating the debate here in Scotland on the Internet and on the doorsteps and meeting places.

And together with losing the right-wing Conservative policies we’ll be waving goodbye to nuclear weapons and illegal wars.