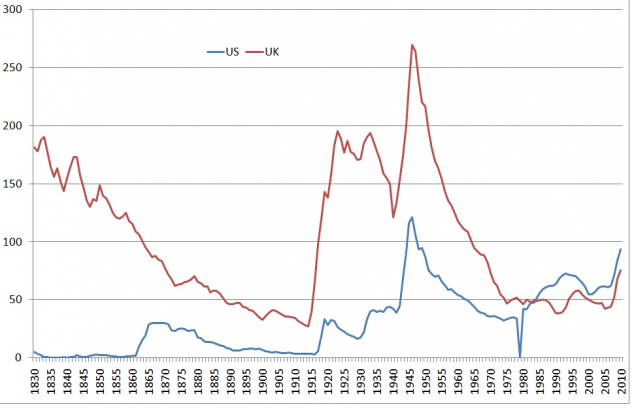

Paul Krugman shows in his blog yesterday how relatively minor is the current British debt to GDP ratio by historic standards. I’ve used the same data source (IMF historical debt database) to show the UK and US data, going back to 1830. (The US data actually goes back to 1793 but for some reason the UK data is missing).

Government debt to GDP (%)

The UK story is familiar to historians as one of war and peace. The peaks of British government debt are those of wars, which are very expensive. And there was very little other government spending in the nineteenth century. The Napoleonic wars which ended in 1815 at Waterloo (celebrated in the UK as a British victory over France, but more accurately a coalition of everybody-not-French over the French, including critically the Prussians) marked a peak of debt for Britain, necessitating the first ever income tax to pay for it. Steady growth, and peace, meant the ratio fell steadily until the First World War in 1914. You see a smaller tick up in US debt when entered the war in 1917 and an earlier peak in US debt coinciding with the Civil War.

A third, even higher spike, came with the Second World War, when British debt reached 270% of GDP, even higher than Japan today. It again fell steadily until the 1970s but has recently started rising again from the relatively comfortable level of about 50% to the less comfortable projection of 78% in 2014-15, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, run by my old friend Robert Chote. (Note that the UK had the luck of North Sea oil revenues from the early 1980s, which kept budgets deficits down and allowed the UK to enter the current crisis with relatively low debt. These revenues are now trivial.)

But by historic standards this is not much to worry about. One of the strengths of the British political and financial system has been its ability to take on a lot of debt and then pay it back. Britain won a long series of wars with France from the mid-18th century onwards (in India, Egypt, North America and eventually Europe) in part by out-borrowing Paris. France had a larger economy and population but its poor financial credibility meant it could borrow less than Britain. The over-borrowing of France in the eighteenth century was one reason for the Revolution of 1789, which I hope the grateful French remember to thank Britain for helping to bring about. (The coup de grace financially was French support for the American revolution, on the basis that my enemy’s enemy is my friend. That last splurge of French spending brought the Bourbon monarchy to its limit, and a few bad harvests finished it off. I’m slightly simplifying the history of the French revolution of course.)

That higher borrowing capacity arose from: i) few defaults since the middle ages; ii) a relatively efficient tax system compared with the hated French system in which the right to tax was sold off to third parties; and iii) a robust constitutional monarchy after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 in which Parliament (representing the tax base) was the ultimate guarantor, not the King (again very different from France and Louis XVI’s extravagant ways).

Britain has shown to international creditors repeatedly that it can repay its debts. To be fair, so has France since it became a Republic and ditched the Royal Family (something we should learn from them, albeit without any guillotines.. mostly). The current low interest rates on UK gilts (government bonds) are partly attributable to this creditworthiness but probably equally reflect pessimism over the British economic outlook, with attendant low inflation.

What the long term charts show is that the key to getting debt under control is GDP growth. The huge debts of the Second World War all but evaporated with steady GDP growth, in both countries. Unfortunately the current long term growth outlook is worrisome on both sides of the Atlantic and we risk a long period of low growth both caused by, and making worse, the debt burden.

Some new book recommendations (1): Why Nations Fail | Simon Taylor's Blog

[…] was the UK because of its “Glorious Revolution” in 1688 (I’ve written about this before). The French Revolution of 1789, followed by Napoleon’s conquests, destroyed the extractive […]

Vincent Cate

You fail to mention that after the war was over and the military was cut back there was no deficit. That makes things easy. If there were no deficit now there would be nothing to worry about.

http://pair.offshore.ai/38yearcycle/#debtlevel