The sacking of Russian finance minister Alexei Kudrin yesterday might not seem very important, just another casualty of Kremlin politics. But the Peterson Institute of International Economics offers an insightful and rather depressing account of how this means Putin is turning away from reform and fiscal responsibility.

Like many people I’ve been puzzled by the inclusion of Russia in the BRICs list of countries that Jim O’Neill of Goldman Sachs coined in 2001. Russia is not a developing economy like China, India and Brazil. During the Cold War, people referred to the rich First World, the communist Second World and the poor or developing Third World. After the collapse of Soviet communism, Russia has a pretty big restructuring job to do and became one of the so-called transition economies. But its GDP per head in 1989 was about 43% that of the US, ten times the level of China (4.7%) or India (3.8%). Brazil was at 21%. (This data comes from The Conference Board, using purchasing power parities, the calculations are mine).

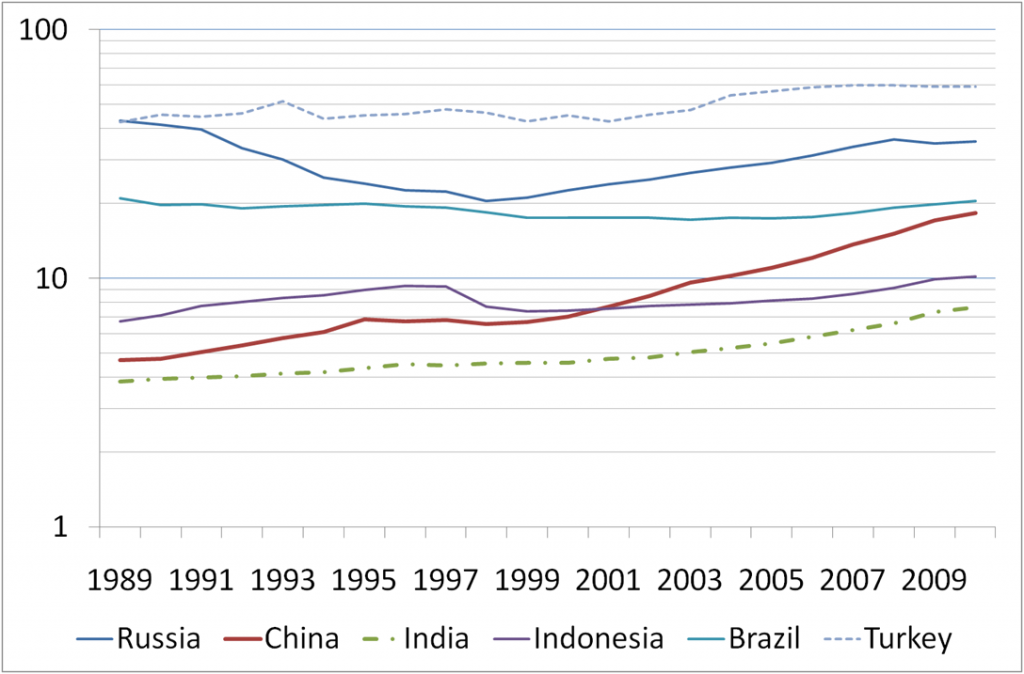

By 2010, Russia had slipped back to 36% while China had risen to 18% and India to 7.7%. Brazil is still at 21%, having fallen then risen in the meantime. This chart, which is an updated version of one used by Martin Wolf for a presentation at the LSE earlier this year, shows things on a log scale. It’s indexed to show GDP per head relative to that of the USA.

The key thing to note is that China (red – of course) shows steady upward progress (representing accelerating growth, as this is a log scale) and India similar but slower growth and acceleration. Russia shows no such transformation, just a recovery from a very weak period, mainly on the back of higher hydrocarbon prices. Oil remains high but gas prices have collapsed owing on the back of US shale gas extraction. But Russia is still on average a relatively rich country.

Note too that Indonesia was on a similar path to China, but from a higher level, but faced a massive setback in the late 1990s because of the Asian financial crisis. But it’s set to keep growing and become one of the world’s major economies. Turkey, already far richer than China or India, is also making slow but steady progress. We could add Mexico as another soon-to-be-major economy. Russia is Saudi Arabia plus Brazil but with a worse climate. I go with the view that it was included to make BRICs easier to pronounce.

Vuyo Gugushe

What do you make of South Africa’s recent inclusion to this group of countries? As a South African it was a great moment to hear that we were now part of the bricS, however, besides being the gateway to Africa, what do you think SA can offer this group?

Simon Taylor

South Africa is certainly a developing economy with enormous potential. It’s a lot smaller than the BRICs, with GDP about a quarter of that of Russia, the smallest BRIC economy. But it’s part of the next group of economies that have the potential to grow substantially faster than the rich economies, including Mexico and Indonesia. South Africa is more important than its size suggests because it is so critical to the whole southern African region. Without a prosperous and stable South Africa, the prospects for that region are poor. But the political situation in South Africa, combined with the great inequality (the two are of course linked) makes the future more uncertain there than in the other economies I’ve mentioned. Having worked in Lesotho for two years I wish the whole area the very best of luck.