I think the world may be fragmenting into increasingly separate economic and cultural regions, one dominated by China, another led but not dominated by the US, with other nations watching and wondering how best to position themselves. This reminds me of the novel 1984.

*

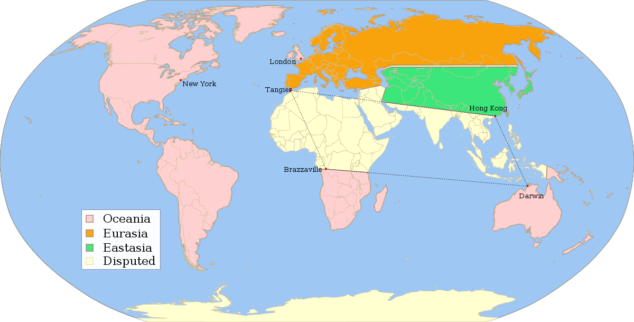

When people refer to a world like that in George Orwell’s novel 1984 they usually mean one of totalitarian control, in particular through oppressive surveillance by the state. While that world is unfortunately looking all too close (especially with the development of facial recognition software) I’m referring to the international world that lay behind 1984‘s all-powerful state. Orwell described a globe divided into three large states, called Oceania (the western hemisphere plus the UK – called Airstrip One in the book); Eurasia, taking in Russia and Europe excluding the UK; and East Asia. It’s not exactly clear where the boundaries are (see below for one plausible map) but Orwell conceived of a world divided along Cold War lines but with a presumably China-led third state aligned with neither the West nor the Soviet Union.

I think we may be heading into a roughly similar division of global politics, as the US-led system that has dominated the world since the end of the Cold War breaks down under the influence of a rising China and domestic US politics. From the end of the Second World War in 1945 until the break up of the Soviet Union in 1991 there was a clear division between East and West, across geography and ideology. Other countries were more or forced to choose to be aligned with one or other of the Cold War adversaries, though India led a partially successful attempt at creating a non-aligned movement (a topic that features in one of this year’s Turner Prize finalists). The capitalist/West side was a system dominated by US economic and military power, which worked pretty well until the rise of OPEC in the early 1970s, when high oil prices punctured the long boom that had until then benefited both advanced and most developing countries.

With the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s, the US remained the dominant economic nation even though the system became one of largely free movement of capital and market forces. That system expanded after the end of the Cold War, as most of the former Communist nations opted for a form of capitalism (not just in Europe but in Asia, including China and Vietnam, despite the continued political control of Communist parties).

The US: large but no longer dominant

Right up until now the US dollar remains the key global currency, something I don’t think will change for years simply for lack of a credible alternative. But that is not the same as continued US economic dominance. The advanced economies’ share of global GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2017 was only about 40%, of which the US was 15%. China was 19% and India 8%. Simply put, the US and the West are not as important a part of the global economy as they used to be. The trend growth of China and India, plus other medium-sized economies such as Indonesia, Mexico and Brazil, is higher than that of the West, partly because it’s easier to “catch up” with established productivity levels of the advanced economies than to advance the best practice productivity itself. The Western productivity growth trend appears to have slowed down markedly in the last 20 years. Although some of the explanation may be statistical (it’s harder to measure and capture the economic value of many digital services) there is a general view in the world of economic policy that growth has definitely slowed. The logic, in the absence of major setbacks for the likes of China and India, is that these developing countries will narrow the gap with the Western economic success.

So the world economy is already looking much more pluralistic than before. A more common term used in the political realm is “multipolar”: there are now various sources of economic, military and diplomatic power in the world, of which the US may still be the largest but it is no longer dominant. On top of that the formerly strong coalition of advanced economies is increasingly at odds, partly owing to President Trump’s policies but the trend was there before him and will probably continue after.

The world has 195 countries but they are organised, either officially or in many cases tacitly, into various shifting groups and alliances. It was ever thus. Although nation states have legal independence, they are forced or choose to trade some of their sovereignty for economic advantage or in some cases to avoid annoying powerful neighbours. So we can see at least three “poles” in this multipolar world, grouped around economic power: the US, Europe and China. If we look further at economic integration, especially trade, we can talk of North America, Europe (mainly the EU), China and Japan as four trade hubs. Japan and South Korea are very highly integrated economically with China but neither wishes to be dominated by its neighbour. Given the very troubled history of this region, the dynamics of power between China and Japan in particular are going to be very interesting. So it’s premature to talk of Eastasia as a single monolith but, given the slow growth of the Japanese economy compared with that of China, it’s increasingly reasonable to talk of a China-dominated regional economy.

Europe: economically strong but politically weak

Europe’s economy is roughly the same size as that of the US, though with a lot more people. Unlike the US, China, and India, which are all continent-sized countries, the continent of Europe (which some people argue is really just a large peninsula on the huge Eurasian land mass) has never been under a single political authority (even the Roman Empire was a largely Mediterranean entity, the Roman army never conquered most of northern Europe – or Scotland). So Europe, if we take that to be roughly the same as the EU, has great economic wealth and influence, especially in trade and in standard-setting. But it has limited political or diplomatic influence. There is no EU army and, apart from the old imperial powers France and the UK, most of Europe enjoys a peace dividend of lower military spending (something that greatly annoys a lot of Americans, not just President Trump, as it makes the NATO alliance seem rather one-sided).

This is one reason Europe is different from the US and China. The other reason why the EU Is a very long way from turning into Orwell’s Eurasia is that Russia, the world’s largest country by territory, is not in the EU and has a very different geography, politics and economy from that of Europe. Although it’s only 3% of world GDP by PPP, it matters because it spends a large fraction of that GDP on the military and is the only semi-global military power to rival the US (though China is catching up). So it is unlikely that “Europe” including Russia will be a single entity any time soon.

The first half of this century is likely to see the continued relative decline of US influence in the world and its replacement in Asia by that of China. This may be only a temporary stage, because if India keeps growing at a high single digit rate, which is plausible (unlike China it has continued population growth for some decades to come) but by no means guaranteed, then it could overtake China’s economy in the second half of this century. Long before that the world may become dominated by the rivalry of the two most populous nations, who happen to be Himalayan neighbours.

An economic “divorce” is in prospect

It’s not just about economics, but that other aspect of globalisation, the media. Google’s Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt recently said that the Internet was splitting in two, because China was building its own online world. Writers from the two Chinese newsletters I follow (SupChina and Bill Bishop at Axios China) both pointed out that this is largely already a fact. People in China have both different companies running their online world, and they have different news and information sources from those in the West (apart from the minority who access The Economist, Google, New York Times, Bloomberg and so on using an increasingly costly VPN). China is also building its own satellite positioning system (as is Europe). The Belt and Road Initiative is mainly an economic project but it’s also about a wider Chinese cultural influence, which is already being pushed globally through Confucius Institutes.

But the core of the growing “divorce” as it’s being referred to, between the US and China is economics. Whatever deal may or may not end the current trade war, the prevailing opinion in much of the US foreign policy world is that the US must do something to stop China catching up in high technology investment. China, mirroring this view, increasingly seems to be determined to build a high tech economy independent of the rest of the world.

What Orwell called “oligarchical collectivism” in 1984 was more an extrapolation from the conditions of 1948, when he wrote it, than a forecast of the future. But the world is, I think, entering a very different phase from that of the previous 200 years when the US, Europe and Japan largely dominated world affairs because of their economic power (which they translated into often brutally effective military power). The US isn’t going away and I think it’s a bit early to write off Europe or Japan, but all face the headwinds of lower productivity growth, and ageing populations, reinforced by negative population growth in Japan and much of Europe. Asia’s future in the next generation is perhaps China’s to lose but there are many other people in Asia who do not want China to dominate. So the world will be a bit more complicated than the three power blocs of 1984. Many countries have hoped for freedom from the dominance of western ideas, but we shall see what they get instead.

Leave a Reply