In a recent IMF working paper I came across the term “North Atlantic financial crisis”. I hadn’t heard this before and it was the first clue of several that the report was written by Indian economists with a well justified gripe about US monetary policy and the damage done by the international monetary system to developing economies such as India. NAFC is a reasonable description of the combination of sub-prime real estate lending losses and subsequent liquidity and credit crunch caused by counterparty risk which started in the US and spread to Europe and then most of the rest of the world. The British, Irish and Spanish financial and economic disasters were in some part independent bubbles, mainly grounded in their own real estate bubbles. But the easy credit of the early 2000s partly followed the US lead.

IMF working papers always carry the disclaimer that they must not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. Indeed, the frustration and barely suppressed anger in this report is presumably much more reflective of emerging economy opinion. The report makes the following arguments.

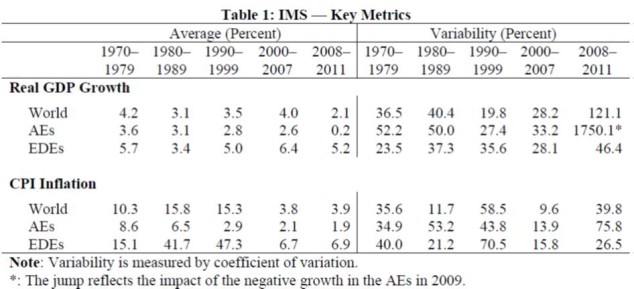

i) The IMS has done a pretty poor job since the end of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in 1971. Economic growth has been lower and there has been a much higher rate of financial and banking crises. The system therefore needs urgent reform. This table, from the IMF working paper, shows that economic growth has been decelerating since the 1970s and the volatility of growth has increased, for emerging and developing economies (EDEs).

ii) In particular the system needs to reflect the balance of economic power as it is now, not in the late 1940s. In particular the IMF shareholdings need to be shifted away from the US and Europe towards emerging economies.

iii) The free movement of capital that followed the end of exchange controls in the advanced economies in the 1970s and 80s has led to huge and destabilising flows of funds that have worsened and to some extent caused banking and balance of payments crises. Funds have flowed from developing to advanced economies – or at least to the US – contrary to economic theory.

iv) The dollar’s role is unsustainable and is likely to be made more so by the expected continuing increase in the demand by emerging economies for foreign reserves. But for the moment there is no alternative to the dollar. Regional plans such as the Chiang Mai Initiative have some potential to replace the dollar but the authors are fairly pessimistic.

v) The report asks for countries to take into account the external effects of macroeconomic policies. This means the US should consider the effect on the rest of the world of its monetary policy. In mid-2013 we saw the effect of markets’ anticipation of the ending of quantitative easing (the “tapering” debate) on financial flows to emerging economies, including the abrupt fall in currencies such as the Indian rupee.

I agree with all of these observations, none of which is really in dispute. Unfortunately I doubt anything will change for the foreseeable future and it’s quite likely that a similar report with even more evidence of disfunction will be written in five years or so.

Why can’t things change?

The Bretton Woods system that ran from 1944-1971 was truly a system, designed by committee (dominated by the US as chief creditor and global hegemon) and based on broadly agreed economic principles. The arrangements since then have been barely controlled anarchy. The US lacks the ability or will to run the system and there is no other country to take over. China is extremely unlikely to match US economic or political dominance at any stage. It will likely overtake the US economy some time soon but it’s falling population means the gap will not keep growing.

And the more fundamental problem is the conflict of interest between the domestic and international responsibilities of a country which is leader of an global monetary system. This is known as the Triffin dilemma after the economist Robert Triffin who first analysed it in the 1960s. The US then (but this is applicable to any country leading the system) needed to run a balance of payments deficit to ensure a supply of international reserve currency i.e. the dollar. But the ever growing supply of dollars and external deficit inevitably led investors to question the value of the dollar. For the dollar to retain its role as lynchpin of the system it needed to keep its value, which meant limiting its supply. That implied keeping the US economy from overheating and avoiding inflation. In the late 1960s the US ran greater budget and external deficits, arising from the cost of the Vietnam War and the growth of President Lyndon Johnson’s “great society” social spending. But that meant a gradual loss of confidence in the dollar.

So the US faced a dilemma: restrain the US economy to cut inflation and raise external confidence in the dollar; or see the external value of the dollar put under increasing pressure. The US understandably put domestic policy first and the dollar was devalued and then floated in 1971. The Bretton Woods system ended at that point. Exchange rates have fluctuated enormously since and a vast pool of mobile capital flows erratically around the world.

Even now the dilemma arises, in a different form. The Fed has kept pumping liquidity into the US economy to accelerate the still weak economic recovery. But that has meant lower interest rates in other countries, especially those choosing (they aren’t forced to) link their currency to the dollar. Even those not linking to the dollar have experienced surges of capital into their economies, until the surge reverses at the prospect of the ending of that liquidity policy.

No country is likely to put international goals over domestic for any period of time. And there is no prospect of an international government that might create some higher order of policy interests, let alone a global currency. The nearest we have to that is the Euro. I don’t think anything more needs to be said about that lessons of the Euro for anyone hoping for global governance or monetary policy.

So the IMF paper is correct but unfortunately unlikely to change anything. Financial anarchy and continued waves of destabilising capital flows are to be expected for some years to come.

Leave a Reply