A key feature of macroeconomic analysis is the relationship between a country’s savings and investment rates. Savings represent income that is not consumed. Investment means spending on assets that will last for some period of time, such as factories, houses, cars and infrastructure. Savings are resources – you cannot invest if you don’t set aside some part of your income. Investment sounds like a good thing, because it should boost income in future, whether directly (the benefits of living in a house) or indirectly (better infrastructure boosts overall economic productivity and growth).

We can classify countries and get quite a long way in understanding their economic problems by examining their savings and investment. The US has, for some decades now, had a relatively low savings rate, reflecting the household sector’s desire to consume most of what it earns. Investment has also been relatively low, but has exceeded savings. This means that the US has been running a current account deficit on its balance of payments, paid for by importing savings from the rest of the world. This is a bit strange for a rich country that ought to be exporting savings to emerging economies.

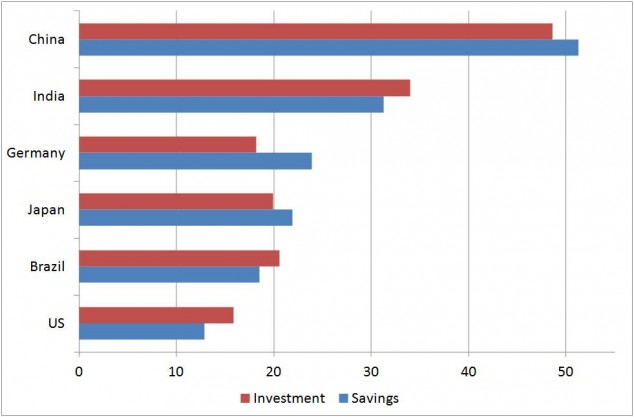

China, the world’s largest emerging economy, is unusual in two respects. First, it has an excess of savings over investment. For a country intending to keep growing fast in future to drag the rest of its population out of poverty, one would expect it to be investing more than it saves. But secondly, China’s investment rate is very high indeed. It’s just that its savings are even higher. This chart shows savings and investment as a percentage of GDP for selected countries in the financial year 2011.

For each country, if investment exceeds saving then it will have a balance of payments current account deficit. Note that Brazil and India behave as emerging or developing economies “should” by having a deficit. The rich countries Japan and Germany behave as they “should” by running surpluses. The US and China are the anomalies and they are the world’s two biggest economies. A large part of the world financial system’s problems, including the instability that contributed to the world financial crisis, can be traced back to these two countries.

Globally all surpluses and deficits must sum to zero (allowing for data measurement errors, which are non-trivial). The diagram above shows savings and investment relative to each country’s GDP. If they were shown relative to world GDP, the US gap would be much larger, accounting for most of the world’s deficit, which is offset mainly by the surpluses of China, Japan, Germany and the oil producing nations.

China’s very high investment rate

Investment is a good thing but can you have too much of it? The decision to save is equally a decision not to consume. Ultimately the value of economic growth lies in the ability to consume, to enjoy the fruits of the economy. So investment is only a means to future consumption. The amount that it is sensible to invest depends on the trade-off between consuming now and consuming in the future. If investing a lot means forgoing consumption for relatively low income people now, that might not be the best decision.

IMF economists (representing their personal views, not that of the IMF itself) recently published a working paper arguing that China is investing too much. As the chart above shows, China’s investment rate is nearly 50% of GDP, which is remarkably high even compared with other fast growing Asian economies in the past.

One potential risk of high investing would be if China was financing this with imported savings, through a current account balance of payments deficit. That was the risk run by several other fast growing Asian economies in the lead up to the Asian financial crisis of 1997. Those countries relied on large inflows of foreign financing which abruptly reversed when investors panicked. The damage done to economies such as Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea was enormous, though they recovered relatively quickly. But China has even higher savings than investment so it doesn’t face this risk. On the contrary, it has built up huge foreign exchange reserves, much of which now finance the deficit in the USA.

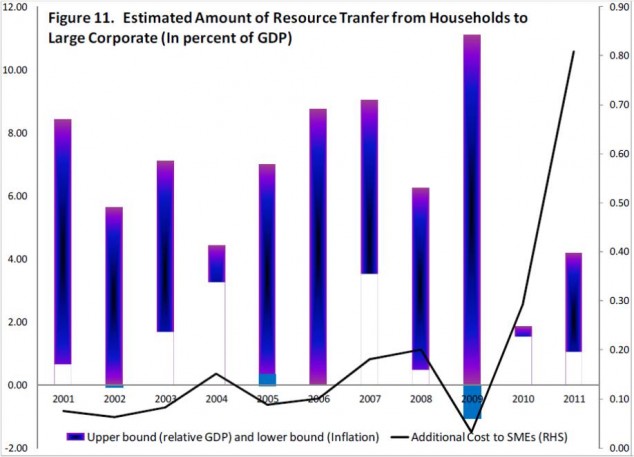

A second reason why investment might be too high would be if it was being wasted on low or negative return projects. In a well functioning market economy (as in textbooks) investment only takes place if there is an acceptable expected return. But in reality investment may be driven by excessively optimistic expectations (eg the US real estate bubble) or by politically motivated goals (“bridges to nowhere” in remote Japanese voting districts). In China a large part of investment is done by state owned enterprises (SOE) funded by state owned banks. The funds come from the deposits of household who lack safe alternatives for their money and who have been rewarded (till recently) with low or negative real interest rates. So there has been a continuing transfer from households to SOE investment. This has boosted GDP growth for many years but it is not costless.

The IMF paper estimates that China’s investment rate is about 10 percentage points higher than it should be compared with other countries experience, as measured by an econometric model. The gap was much smaller until the last decade. They estimate the cost of this over-investment as about four percent of GDP. This may not sound a lot but it represents an annual transfer of resources from households that is about ten percent of total consumption. To the extent that it falls on below average income households the cost is far higher.

What is this cost? It is the loss of income to households from having to endure low interest rates on their savings, a form of financial repression (see this blog for more on that). A second cost, though much smaller, is that large companies enjoy subsidised borrowing rates at the expense of the small and medium enterprises (which is much the same as saying the private sector) which pay higher rates than they would if the system were more balanced. As SMEs are the more dynamic part of the economy, the whole process means that the quality of Chinese economic growth is lower than it would have been, even if the quantity has been kept high. This chart shows the IMF working paper estimates of the costs.

None of this is necessarily controversial. The Chinese government, which recently appeared to reaffirm the previous government’s economic policy, agrees the need for rebalancing away from high investment towards higher consumption growth instead. But it’s relatively easy to cut investment, which can be done by telling SOEs and provincial governments to build factories, houses and infrastructure at a lower rate. Raising consumption fast enough to replace the reduced rate of investment is not so easy.

Additional reading

China: IMF Article IV Mission Report, 2012

Leave a Reply