Although there is nothing much to rival the views from the top of the Empire State Building and GE Building (the “top of the rock”) the part of New York that has only recently become my favourite is more remarkable for its interior than the outside. The New York Public Library’s main site, now known as the Steven A. Scharzman Building, is located on Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street, roughly midway between the towers mentioned above. It has a fine exterior but inside is the real treasure.

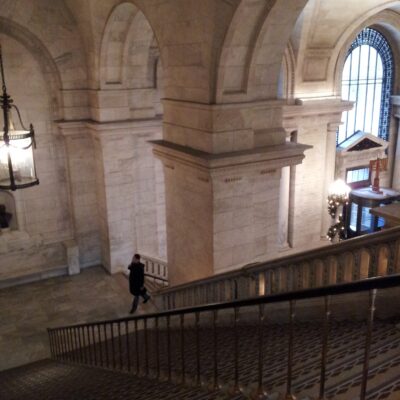

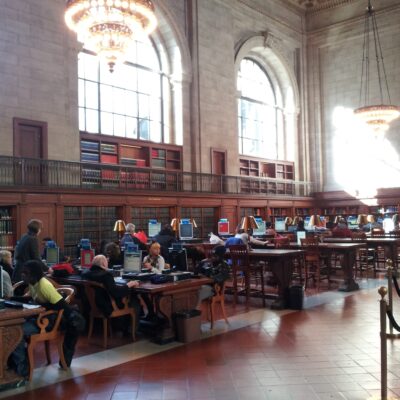

For this is a beautiful and very public building, dedicated to giving the people access to learning. It has several fine reading rooms and expansive, almost luxurious public areas, with grand stone staircases and magnificent ceilings. The building on Fifth Avenue opened in 1911. It is one of the two finest examples of the Beaux-Arts neoclassical style of architecture that became very fashionable in the US in the late nineteenth century, the other being Grand Central Station, also even more magnificent on the inside than the outside. It was wildly popular when first opened and remains a full working library today. But you can just walk in off the street and use the reading rooms or just admire the interior, though it is polite to give a donation.

The Library is also a testimony to the power of philanthropy, a driving force behind so much of New York’s architecture and amenities. The library started with a $2.4 million bequest in 1886 (a lot of money in those days) by former New York State governor Samuel Tilden. Two existing privately funded libraries, the Astor and Lenox that were in financial difficulties at the time were combined with Tilden’s endowment to create the New York Public Library plan in 1895, for a genuinely public institution.

The private giving continued. There is a large stone panel recording further donations from the Astor family, among the richest in America at the turn of the century. Andrew Carnegie, Scottish immigrant turned steel magnate and possibly the richest man in the world after selling his business to JPMorgan for $480 million in 1901 (John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil may have been even richer) gave $5.2 million to support the wider branch network of the NYPL. Carnegie, whose name lives on through donations to Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and countless other institutions, was a pioneer of modern philanthropy. In his business life a ruthless and controversial figure, he was outspoken about the importance of giving away wealth and highly critical of those who stored up riches, saying “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced”. (The word thus is often omitted when this is quoted.) Carnegie opposed indiscriminate charity and emphasised giving to those who would help themselves. (*)

There is a whole wall devoted to library donations, grouped in an amusingly meritocratic way by the amount. The premier league consists of those who gave more than $1m. Somewhat humiliatingly, I should have thought, Donald Trump’s name appears in the fourth division of $25,000-$49,999.

Blackstone CEO Steve Schwarzman’s donation of $100 million in 2008 was big enough to have the whole main site library building renamed for him. I don’t know if that was part of the deal or just an appropriate recognition of his generosity. It does seem that part of the motivation for donating is a sense of public recognition and permanent memorial. Perhaps my British instinctive dislike of ostentatious spending makes me more inclined towards another $100million donation in 2010, that of hedge fund billionaire John Paulson to Central Park. He will have no public monument to his gift though he was the first to point that as the park is, in effect, his front garden, he will benefit from his own generosity.

British churlishness aside, both Mr Schwarzman and Mr Paulson are to be greatly congratulated on putting some of their wealth to good use for the wider public benefit. At a time of very high and rising income inequality in the US and globally, the least we can hope for is that some of the massive concentrations of wealth leave some enduring public good.

Libraries gave us power

Inside, in the peaceful but studiously intense atmosphere, the Library is just so, well, civilised. Like all libraries today, most of the services are now hidden and intangible, distributed online. (At Judge we are forbidden to refer to the library, but must instead talk of the Business Resources Centre). But there remains something charming and wonderfully democratic about being able to walk into the library and sit and read a book (though you have to be a member to take it out). All this is an expansive and warmly lit room with fine decorations and exquisite period detail. Public libraries provided access to self-improving working people in the era before free mass schooling (as the Manic Street Preachers said in the magnificent A Design for Life, “Libraries gave us power”). They are under assault in the UK from falling local government budgets. Whoever the British equivalents of Carnegie, Schwarzman and Paulson are, we need you.

*

(*) He also once said, in total contradiction of a basic principle of traditional finance theory that “The way to become rich is to put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket.”

Diana Kolpak

Library funding is similarly under attack here in Canada, Simon, including funding for our national archives. Sigh. I guess Conservatives fail to understand where the true wealth of nations comes from…