In recent years there has been a fierce debate about the effectiveness of foreign aid, with opponents such as William Easterly arguing that most is wasted and that it often props up regimes that harm their population’s long term future. Aid, or ODA (official development assistance), is still given by most rich countries, which claim to be trying to target it better to get the desired result – a sustainable reduction in poverty.

A challenge for policy makers is that most of the world’s poor now live in countries which are classified as middle income, not low income. The countries with the biggest absolute numbers of poor people, China and India, are both officially middle income countries. Lower middle income, on the World Bank’s definition, starts at $1,006 per capita GNI in 2010 dollars (GNI is gross national income, a broader definition than gross domestic product, GDP). The top of the high middle income range is $12,275. There is therefore a vast difference within the middle income category. China’s 2010 GNI per head was $4,270. India, at $1,270 is also technically a lower middle income country but clearly much poorer, despite relatively fast economic growth, because its population has kept growing.

Any definition of high or low income is somewhat arbitrary. Whether you live on $2 a day (Cambodia, Kenya) or $3 (Lesotho, Nicaragua) may make quite a difference to the quality of life. Yet these are still wretchedly low numbers.

A recent briefing note from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) in London shows that most of the world’s poor are in India and China, countries that get low levels of aid relative to the size of their economies.( I was an ODI Fellow years ago, working for the Central Bank of Lesotho. ODI’s main role is as a leading research centre in aid and development matters.)

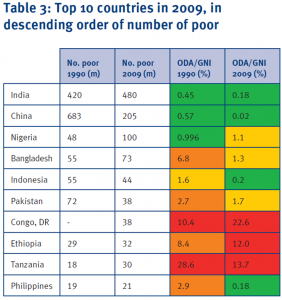

This chart from the ODI report shows that countries with the most poor people have low amounts of ODA relative to their national income. The few countries with relatively high levels of aid (DR Congo, Ethiopia and Tanzania) have far fewer poor people than either India or China.

Source: Jonathan Glennie “What if three quarters of the world’s poor live (and have always lived) in Low Aid Countries?” ODI, April 2012If you are one of the 205m remaining poor people in China, it is scant comfort to know that on average China is a middle income country, largely because of the high incomes earned in the coastal provinces. This is an example of what my management science colleagues call the “flaw of averages”. We use the average (usually mean but sometimes mode or median) to summarise information about something. It is a measure of central tendency and often a good guide but can be misleading. British weather annually shows about the same average temperature and rainfall as previous years, but the monthly variation is extreme and provides endless scope for comment and complaint. This amusing book gives plenty of examples of the danger of making decisions based only on the average, including the (not very good) joke about the statistician who drowned crossing a stream that was on average only three feet (one metre) deep.

The fact that there were still two hundred million poor people in China in 2009 is not a criticism of Chinese policy. China has done more by far than any country in history to attack poverty; it just has a long way to go. From 1990 to 2009 the number of Indian poor rose by about 20m; China’s fell by 478m. And poverty is not captured well by income statistics. Equally important are measures of education, health, literacy and women’s rights. Amartya Sen, Indian Nobel prize winning economist (and former Master of Trinity College Cambridge) has pointed out how much better China has done than India in the last twenty years in respect of these measures of quality of life. This reflects government policy and effectiveness, not economics. Life expectancy is nine years higher in China than India, infant mortality is 50 per thousand in India compared with 17 in China, female literacy is 80% compared with 99% in China and so on. Sen also argues that India scarcely does better than Bangladesh on many indicators, despite having nearly double the GNI per head, which further undermines the significance of per capita income as a guide to the real experience of the poor.

The question for governments giving ODA is, should you target low income countries or the countries where the poor mainly are, which includes middle income countries? There has been some controversy in the UK in recent years about giving ODA to India, which is now the world’s eleventh largest economy at market exchange rates and fourth largest at purchasing power parity (a method of adjusting for exchange rate distortions). The UK is eighth and ninth on each definition (source: CIA Factbook). When I was working at the World Bank years ago I said something about India being poor in the presence of an Indian law student who was doing an internship as part of her PhD at Stanford. She fiercely declared “India is a rich country with too many people.”

This is one of those statements that is both trivial and profound. Poverty is obviously about the amount of income per head, not the size of the economy. A small economy with very few people, such as the UAE, would be more congenial to live in than a larger one with very many people, like India. But India does indeed have a large and powerful economy, capable of supporting a big army, a nuclear weapons programme and some of the world’s most successful multinational companies (it is ahead of China in this respect). But it has not yet spread that wealth to the mass of the people or found a way for them to raise their own standard of living.

No simple ratio is going to tell you all you need to know about poverty. But governments have to guide their policy somehow, and defend the results to an innumerate and impatient media. So expect the flaw of averages to remain a challenge for poverty policy.

Leave a Reply