The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a great example of an institution that was created for one purpose – to police the system of fixed exchange rates set up in the 1944 Bretton Woods treaty – which has survived and evolved to do something quite different – provide emergency lending and financial advice to countries in a world of mostly floating exchange rates. It has a somewhat chequered history in respect of what now looks like misplaced enthusiasm for countries opening their economies to the free movement of international funds. That policy took a big hit in the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and has been more or less abandoned since.

The IMF is also unpopular in many countries which had to borrow from it under pressure of balance of payments crises and resented the conditions that the Fund attached to the loans. This is slightly unfair because in most cases the IMF was simply insisting that governments take steps to cut spending and reduce unsustainable deficits, steps which the governments knew were essential but found it politically convenient to blame on the IMF.

But the IMF has many excellent staff, is a centre of outstanding research and policy analysis and is the only international financial policy institution we have. (The World Bank has a potentially important role to play in economic development but is largely irrelevant to matters of global economic and financial governance). So rather than criticise it, we should build on its many strengths and address its most immediate weakness, which is that its voting structure doesn’t represent the actual economic power of its members.

This is because the Fund was set up a long time ago when many of today’s emerging economies were far smaller and in some cases weren’t part of the international financial system. But the global distribution of economic power has changed a great deal since the 1940s. For the IMF to have credibility as an institution that just might be the focus of a new international financial system, its national allocation of votes needs to reflect that change.

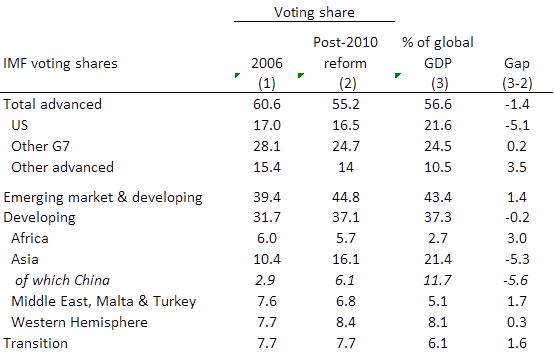

This table shows the voting shares in 2006, before the latest round of reforms, then with the reforms agreed in November 2010 at the G20 meeting in Seoul, but not yet implemented. It also shows the shares of GDP. The last column shows the excess or deficit in votes relative to national/regional shares of GDP.

Note that the advanced economies in total have a small deficit in their votes relative to GDP of 1.4 percentage points. The main shortfall is that the US has a gap of 5.1 percentage points in its votes relative to GDP. There is a partly offsetting over-representation by other advanced economies, chiefly smaller European economies. The other major shortfall is for Asia, which is dominated by China’s gap. Although it has about 21% of global GDP, calculated according to a “blended” formula (see below), China will have only 6.1% of the IMF’s votes, if and when the 2010 reform happens. Its current vote is only 2.9%. Presumably the 2010 deal was negotiated on the basis that both the US and China were under-represented, creating some sort of justice.

But the US can be relaxed about its under-representation of voting share because it will still have a de facto veto after the reforms. Major changes in IMF rules require an 85% majority vote and the US will still be able to block this if it wishes.

The reason for the delay in the voting reform is the US Congress. In January 2014 Congress failed to vote for the legislation required to implement the changes. This in turn reflected the political polarisation in Washington DC, so that anything proposed by the President will almost automatically be opposed by the Republicans. It also tapped into a longstanding scepticism among many Americans about international institutions, even the IMF. Peterson Institute scholar Edwin Truman argues that this failure to vote through the reform is not only damaging to the role of the IMF (the vote was also about increasing the IMF’s financial power) but damaged the interests and influence of the US itself.

It is certainly disappointing. The real loss of power in the 2010 reforms is from Europe. The new IMF would lead to two European executive director seats being cut. Europe would still have disproportionate voting rights but it would lose some of its board power. The US brokered the reform package as a compromise between the emerging economies and Europe, with the US not losing any real influence. Yet it is US politicians who are now blocking changes that would both strengthen the IMF’s ability to help stabilise financial crises and make it more legitimate in the eyes of the citizens of emerging economies which now make up roughly half the world economy.

Other reading

Edwin Truman (Peterson Institute for International Economics) IMF reform is waiting on the United States

Simon Johnson (former chief economist at the IMF, now a professor at MIT) The importance of being boring

Earlier blog articles related to the IMF: Rekindling the spirit of 1944? The once and future king? The IMF; The IMF and the French; The revival of the IMF

IMF Policy Paper: Quota formula – data update and further considerations (surely a contender for most dull sounding paper of all time?)

IMF technical details of effect of 2010 reforms on quotas: http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2011/pdfs/quota_tbl.pdf

UPDATE: additional article by Edwin Truman arguing that the US should allow the IMF to raise funds from other countries and dilute its vote, risking its veto but allowing the IMF to still function.

Note: blended GDP shares

The GDP share shown in the table is calculated using a formula: 60% weighting by GDP at market exchange rates and 40% weighting by GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP). PPP is intended to correct for the fact that market exchange rates are often a poor guide to the true size of the domestic economy in many emerging economies. The value of economic output in China and India, for example, is materially higher when calculated at PPP. So this blended formula is a nod in the direction of granting more recognition to the emerging economies but not so much as to upset the delicate diplomacy by which the richer economies gradually concede power.

Leave a Reply